Introduction

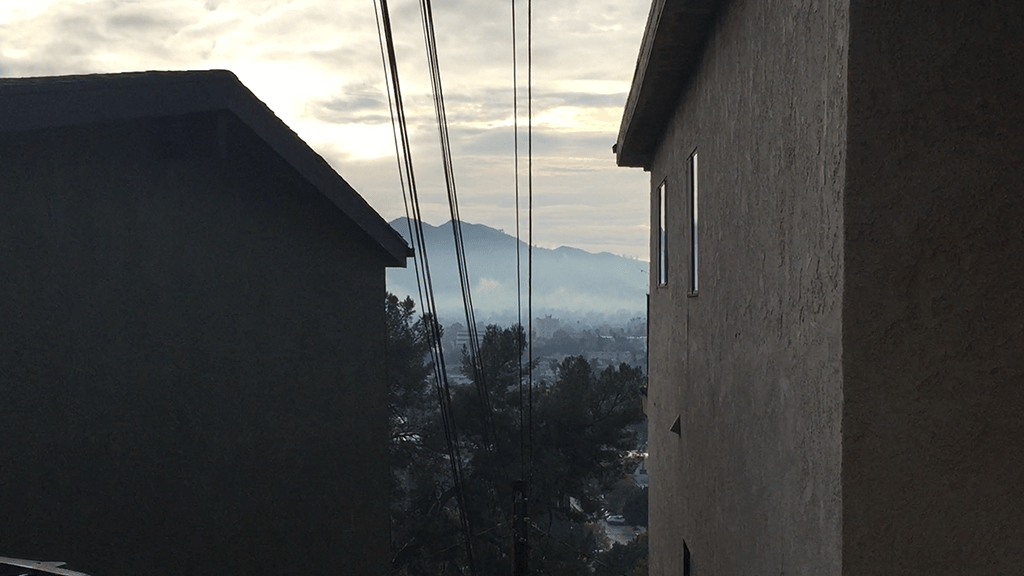

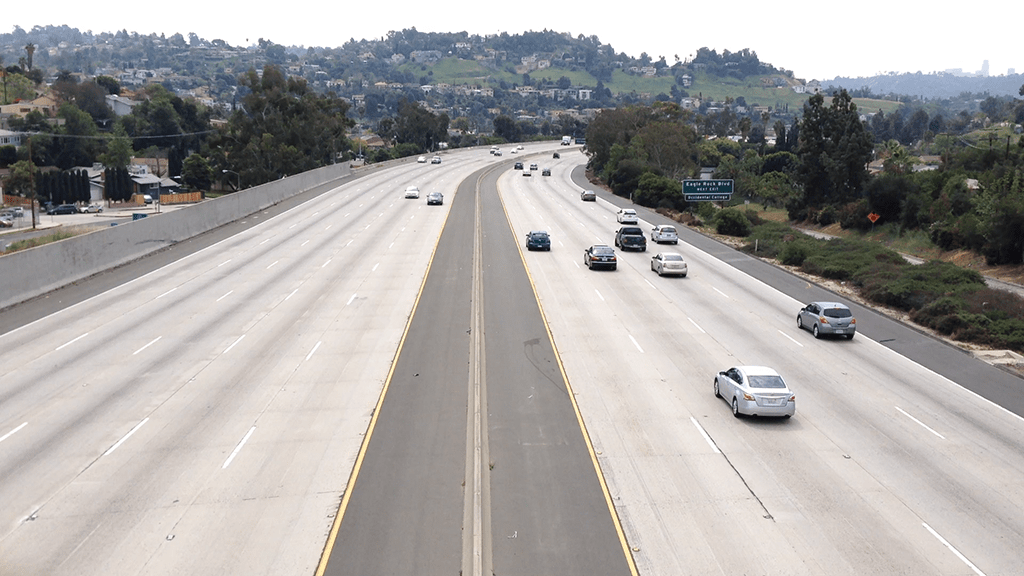

The idea for Additional Parking, the video, started in the early 2000s when I was working as an adjunct Art teacher at various community colleges in what is sometimes referred to as the Southland. On different days of the week, from my apartment in Silverlake, I would drive out along the northeastern foothills to Rancho Cucamonga, down the South Central corridor of Los Angeles to the beach adjacent border of Gardena and Torrance, and on Friday nights, I would slice diagonally through the heart of the metropolis, going way down through the Orange Crush to Santa Ana. These long and lonely commutes would traverse an enormous amount of space densely layered with collisions of urban, suburban and industrial development. During this time, I slowly absorbed many things about Los Angeles, but mostly the strange way that all the small cities and towns slowly dissolved into one another along the way. Framed by a car window, on freeways always full of traffic, I would find myself cinematically tracking by them, unconsciously recording the views as I slowly inched along. Rancho Cucamonga, Torrance, Santa Ana, and central Los Angeles are all very different manifestations of space with their own unique cultural influences, urban configurations and aesthetics. While moving between these cities, the transitional geography softens their distinctions and they all begin to feel like they’re a part of the same mess. One can choose to ignore this and think of each town as a very different place existing in its own geographic vacuum. I eventually chose to embrace all of its complexity and all the little differences that add up to a unified and incomprehensible form of regional psychosis. It is a stream of visual information and intellectual stimuli relentlessly overfilling one’s vision and flooding the senses, while quietly drowning your perceptions of reality. The city, its communities and its people, are continually conversing, exchanging, decoding, and re-coding — seeking to remedy or resist the endless momentum of their collective dialogue.

When I first moved to Los Angeles, I was sporadically employed and constantly broke. I began a painting practice in half of a garage that was part of my apartment rental, using industrial paints that had been returned by customers to the local hardware store. During the years that I developed this work, using secondhand exterior paints, I also sourced other materials from that same hardware store for art making purposes. Wood for stretchers, saws, primer, nails, staples, glue, brushes, etc. For a full decade I hardly even stepped into an art supply store. The work of that period has the look and feel of that unusual supply and production chain. It has a strangely industrial look to it, fast and cheap. Even today, despite the fact that I can afford better supplies and do use them, the work I make is still linked to some of those ideas but also to the fundamental notion that there are environmental influences on one’s work — both physical and intellectual. I can’t help but think of Los Angeles as a lab for artists. The city is a gigantic archive of visual references, citations and influences. It provides artists with a wealth of visual languages, cheap garage-like workspaces and a rough-hewn collective belief system that allows you to turn social networks on and off, like a faucet. It conditions not just the work, but you as well. Additional Parking interprets the city as an artist would, to value it in terms of cultural production and intellectual nourishment.

As a teacher, and someone very interested in color, line, texture, form, and the environmental influences of urban life, my first attempt to record this idea was to ask my students, from each separate community I taught in, to develop conventional color palettes based on prompts I would come up with — imagine, create, and name the colors of the beach, for instance. The idea was to build color systems but also to scrub through many of my students’ preconceived ideas of color. I would eventually ask them to develop their own color palettes, secretly hoping they would come up with palettes that bore regional marks and tell-tale signs of difference based on where they lived — the foothills, the westside, the inner city, or Orange County. It was a failed experiment, although everyone’s palettes were a unique set of colors, for the most part, they were all loosely consistent no matter what area of town they had originated from. Nevertheless, the root of this exercise set in motion the idea that the city could be a resource, both material and inspiration for the production of art. Of course this could happen in any city or town, but what specifically could be made of Los Angeles? Is there something about the city, its people, its aesthetics, its politics and philosophies, that could work its way through the hands of its inhabitants?

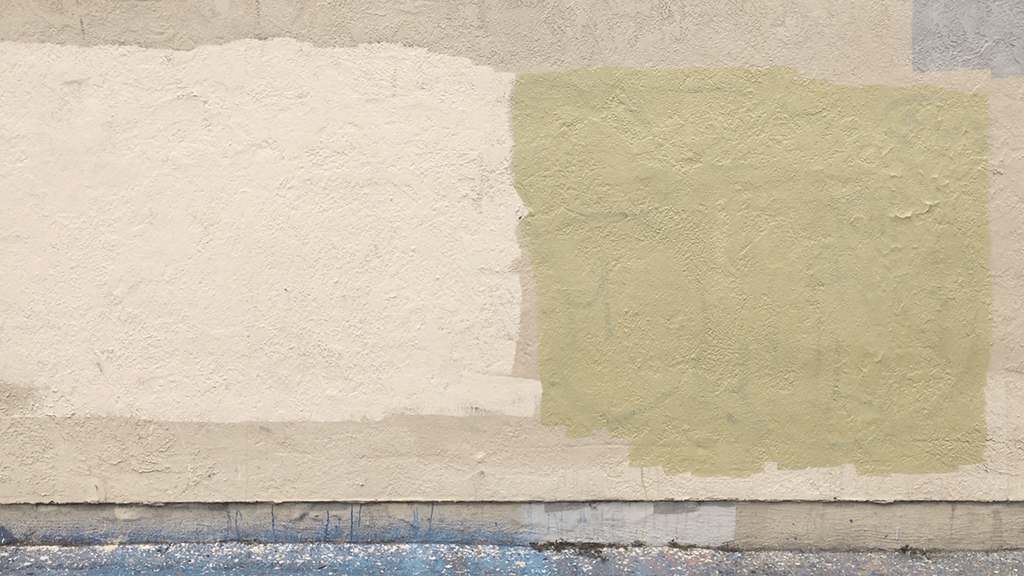

For my next attempt, I decided to buy a nice digital point-and-shoot camera — fancy for the time — to photograph the painted stucco on buildings in each community I worked in. I would then assemble a series of studies in urban color, texture, and form. As an example, the planned communities of Orange County have very strict color codes for exterior homes and neighborhoods, whereas in Los Angeles, particularly where I now live in Glassell Park, there seems to be absolutely no rules at all. Taking these photographs got me outdoors and looking at things most people take for granted. Color and texture are commonplace features of our neighborhoods that we seem to forget and no longer see. Although the eventual realization of my initial project only amounted to images of my neighborhood — I’m sure I would have been tarred, feathered and escorted out of the city if I was caught filming homes in Irvine — it did manifest into a book that is a faithful statement about Glassell Park and the thinking of an odd middle-aged man walking about with a little digital camera. Although it was an interesting study, it still wasn’t what I was trying to figure out about my relationship with the city.

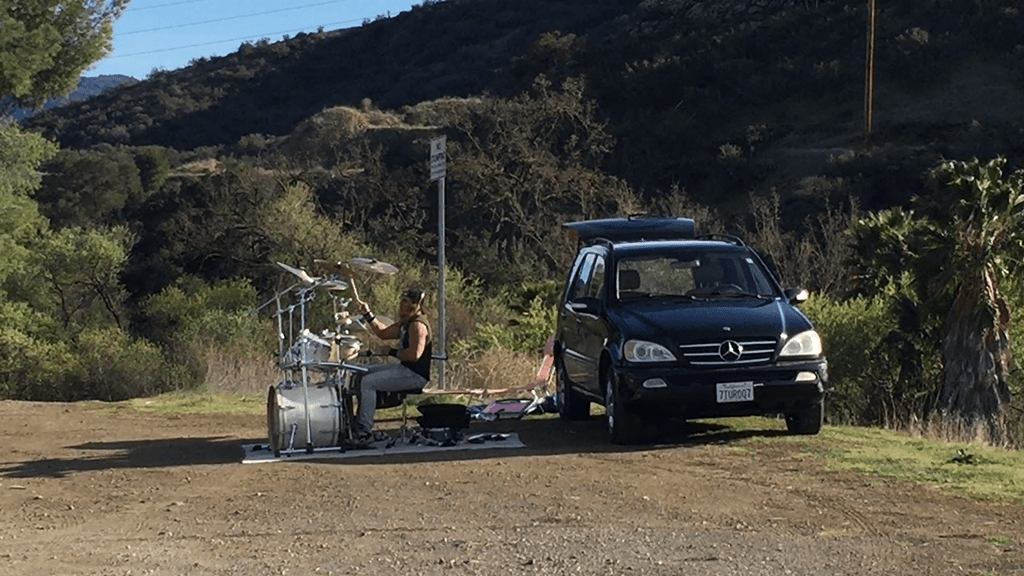

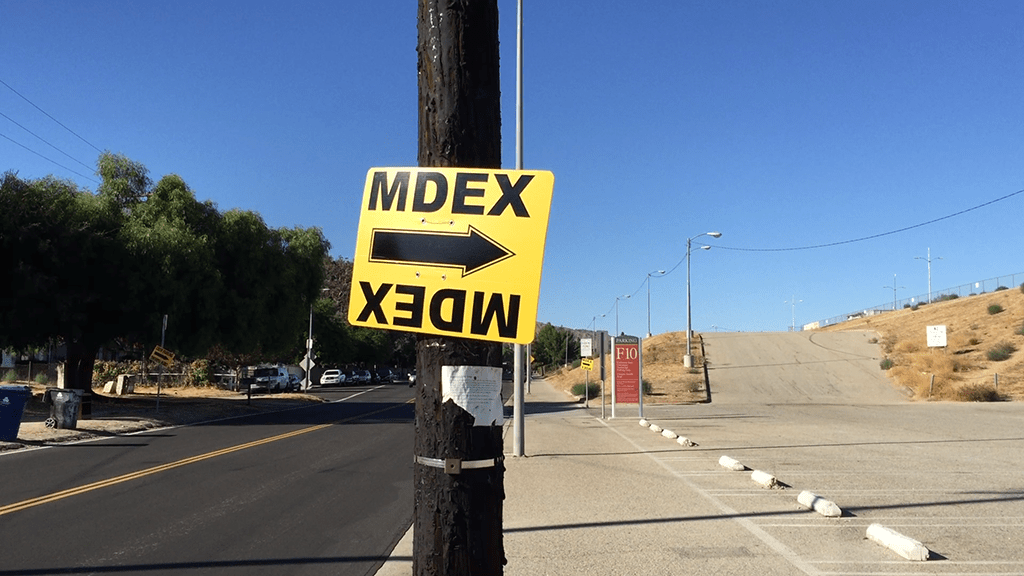

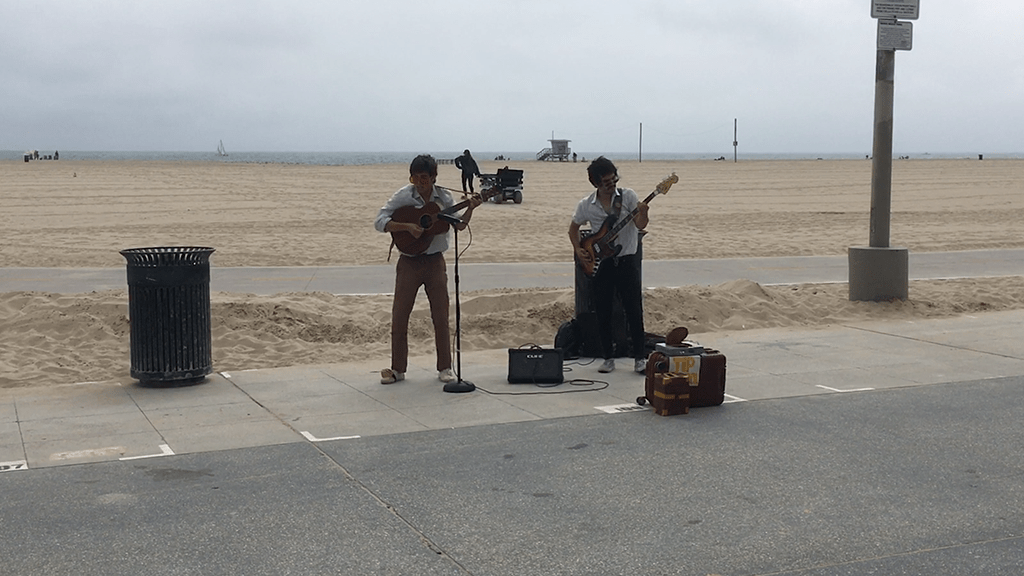

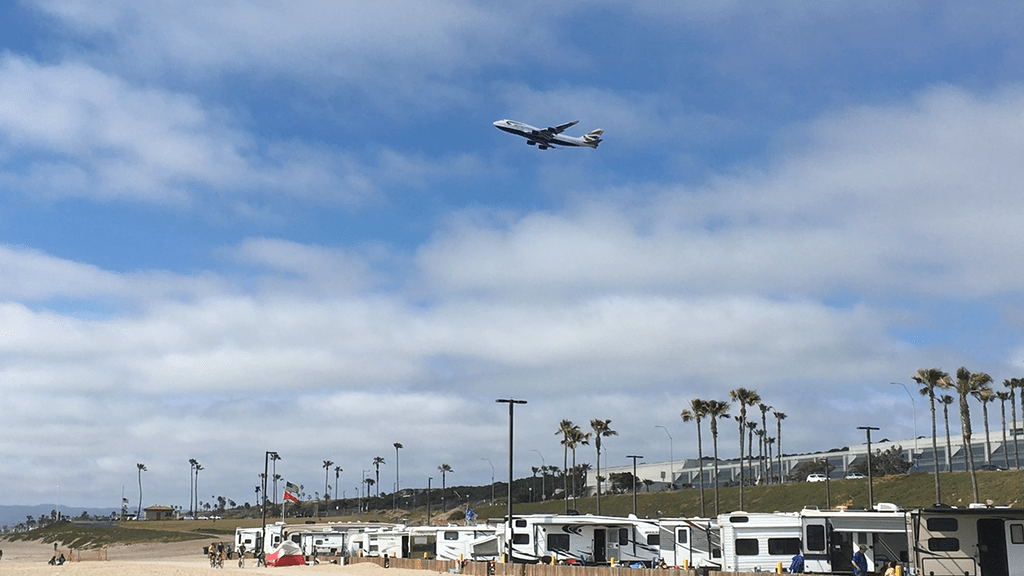

A factor that played in my favor was the development of technology, the iPhone had evolved to a point where it not only shot good photographs but amazing high-definition video as well, all on a device that easily slips into a back pocket. While taking the photos for the Glassell Park book, I realized there were so many more odd, subtle and interesting things I was finding along the way, something that video was better suited to communicate, so I embarked on a project that would occupy much of my spare time for the next five years. I started shooting one to two second iPhone video clips of not just my neighborhood, but the entire central city. This mostly covered everything west of the 710 freeway, but also some peripheral desert and mountain communities. Additional Parking starts in northeast Los Angeles, where I live, moving outwards from there in anchored circles, east to west, from the mountains to the sea, systematically capturing fragments of the city in approximately 22,000 handheld shots. The small one to two second clip times anticipated a long video, one that required visual equity. I wanted to give everything equal weight and give viewers a regular, almost mechanical, rhythm to move along with. Though not planned, this amounted to a 10-hour run time, which still feels like it only lightly touches upon all that is out there to see. My son, who assisted me for much of the filming, once joked that once we were finished, we should simply reverse course and film our way back home knowing that we would find an entirely different city while doing so.

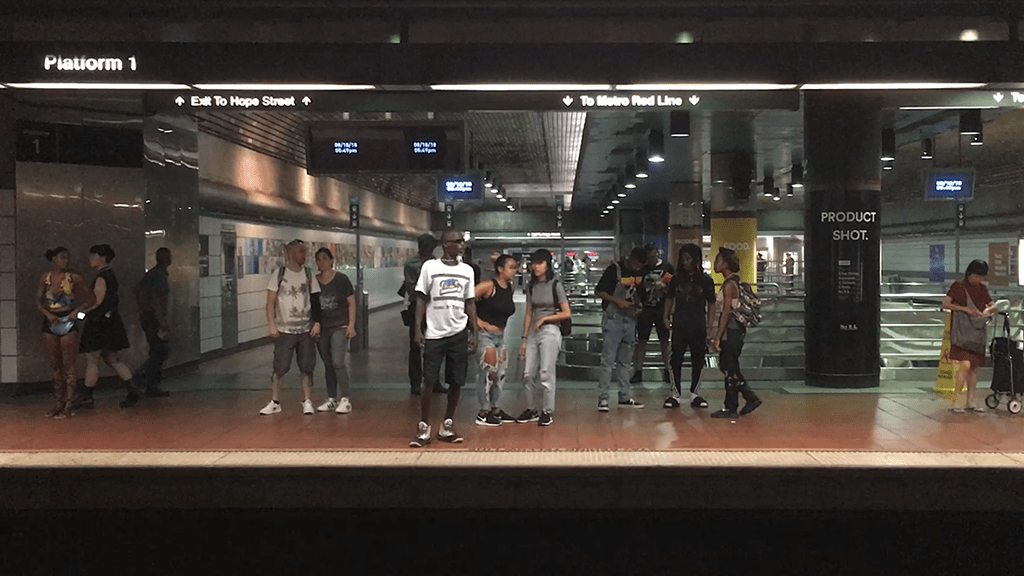

Filming was an ongoing process and could be a part of any given day or moment. Imagery was gathered as short clips shot during walks and errands, but also incorporated hundreds, perhaps close to a thousand weekend outings to different parts of the city. There were also specific times where I would set out to unfamiliar areas of the city to wander around for hours. I would start by looking at Google Maps, Wikipedia and other relevant websites, assessing the place and the things I should pay attention to. Where is the main commercial street? How far out does the housing go? And are there industrial areas, bridges, parks, monuments, or other highlights that I should be looking for? This process would help acquaint me with places I wasn’t already familiar with. I’ve only been to Sylmar, Canoga Park, and Carson once, and may never return. Sometimes I ventured out to areas far enough away from my home so I would stay in a local hotel and resume shooting in a neighboring community the next day. Staying at hotels in the city you live in to avoid excessive commuting is a reflection of how big and spread out Los Angeles is. Despite this, these overnight trips helped expand the timeframe required to walk, cycle, ride public transportation and drive my way around 500-600 square miles of urban space to film it.

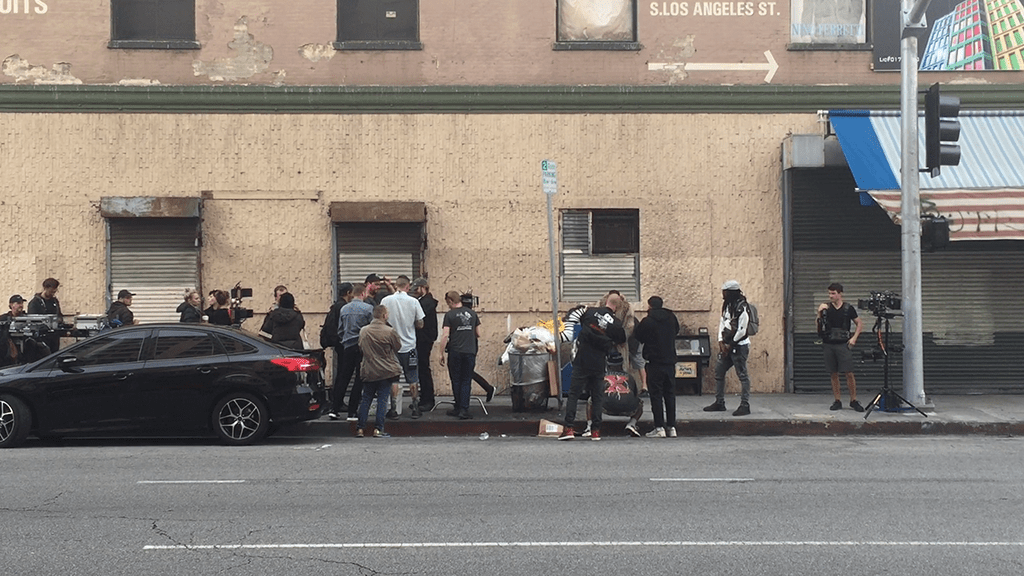

The final cut is a long work that incrementally reveals patterns and changes within the geographies of the city and the distribution of its inhabitants. Changes in ways of thinking, political discourses, and psychological or philosophical methods, are gently evoked through the different images of architecture, transportation, signage, dress, food, wealth, poverty, faces, rituals, celebrations, flora, fauna and, in essence, the cultural practices and artifacts of the hundreds of communities that make up the city. These elements are the physical material of this work, the crosshatched haptic interface the viewer grips onto and interlocks with. The piece is neither a documentary nor a precise mapping of the city. It is rather a comprehensive and immersive survey that aims to convey how the residents of this city experience and live through a particular time in a particular place. I had no interest in developing narrative structure or revealing prefabricated tension beneath layers of Hollywoodish cliché and metaphor. The aim was to record and assemble a mass of difference, to pull together a gigantic tapestry that would be easily consumed but painfully digested. Like film and television, Additional Parking is paced to force-feed the viewer, vehemently so, but unlike them, it is celebrity-less, difficult to bond with and seemingly endless. Its constant flow of meandering imagery is relentless, amplifying the senses while also distracting them. It resists the viewer’s full attention.

These Field Notes endeavor to slow all of this down. Writing has given me time to account for and reflect upon what I have witnessed in my Homeric travels around Los Angeles. These notes attempt to convey some of the journey. In this sense, each small essay or note is like the handwritten text on the back of a postcard. The video, being a kind of time-based digital Neo-Divisionist work, lends itself to individual frame analysis. In looking at the stills I am now a posthumous viewer, a pathologist of sorts. Los Angeles is so vast one can be a resident and a tourist at the same time. Much of what I saw and filmed was unfamiliar to me, leading to many new experiences and discoveries. In this sense, the notes not only reflect upon aspects of Los Angeles life, but they’re also an exploration of learning to live here.

I have lived in California since 1986. It is my home and, in many ways, it is my utopia. But it is also a problematic and difficult place full of contradictions. Los Angeles is a city still in the making, an unstable and somewhat tumorous part of the republic without a secure sense of civic identity or strong leadership. It’s a part of California so wayward and troublesome that the rest of the state relentlessly tries to secede from it. There are great things about the great Los Angeles metropolis, but the criticisms directed at it are almost always true. It is a city simmering with dysfunction, with layers of anxiety, conflict, loneliness, violence, misery, sadness, isolation, stress, sickness, and death. It’s not a city that you should move to in the hope that it will improve the quality of your life. It is a working town and most people who end up here come to make a lot of money or some sort of a name for themselves out of seemingly nothing. It’s as if the California Gold Rush never ended.

Los Angeles has always been a kind of grand social experiment; it is a huge proving ground where the promise of a modern, autonomous, self-sufficient living was set in motion over a century ago. Despite the obvious veneer, people still migrate here to take part in that vision of utopia, find their piece of it, and live with the slow burning, laconic maintenance of day-to-day life here. Los Angeles is the city suggested in Additional Parking, as it is, was, and will be in future versions of itself. A city with a strong current that can at times run dry yet swell up and engulf anything in its path. The flow of the city’s dynamics keeps you distracted from many of its chronic social and political problems. Beneath the promise of the healthy, prosperous, sun-drenched Southern California lifestyle lie some ugly and traumatic truths. The city is the cause of many of our problems, but given enough distraction, some patience and an open mind, perhaps it is also the remedy.

“The charming landscape which I saw this morning, is indubitably made up of some twenty or thirty farms. Miller owns this field, Locke that, and Manning the woodland beyond. But none of them owns the landscape. There is a property in the horizon which no man has but he whose eye can integrate all the parts, that is, the poet.”

Ralph Waldo Emerson

Nature, 1836

“It is what it is, that’s what it is.”

Charles Bobbit, Fred Wesley & James Brown

Mind Power, 1973

[CLICK ON THE RED MARKER TO VIEW VIDEO] — The red markers link readers to hourly intervals in the Additional Parking video. This first one connects to the beginning.

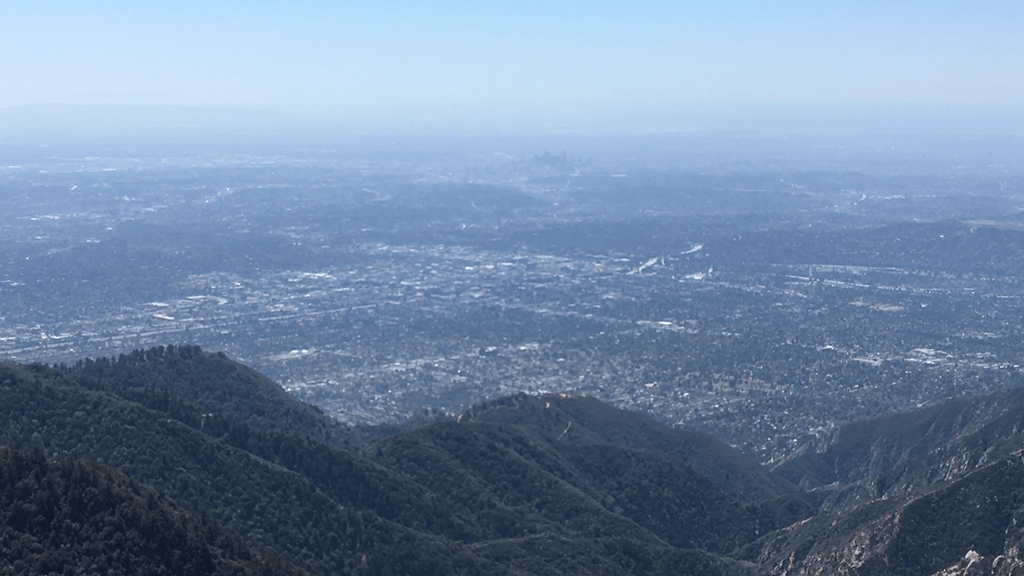

Above, Mount Wilson Observatory.

This image was shot from the parking lot of the Mount Wilson Observatory, which stands approximately 5700 feet above the basin below it. It shows the city of Los Angeles and the complex relationship to the landscape that defines it. The mountains in the foreground lead into the complex sprawl of Los Angeles and its neighboring communities. La Cañada Flintridge bleeds into Glendale, Pasadena, and further into Los Angeles itself; while Santa Monica, Venice, and other beach communities dissolve into a mixture of marine haze and pollution that is typical of the late spring months in Southern California. The horizon line, defined by the Pacific Ocean, softly runs across the upper third of the image. The extreme contrast of the mountains and the sea foreshadow many of the dramatic differences in the economic, religious, political, and cultural views of the people who call the area home.

As an early shot in Additional Parking, this image literally sets the stage for what will unfold over the next 10 hours. The viewer descends from the mountain and becomes immersed in many of the details of life in Los Angeles. The oncoming rush of imagery sidewinds its way across the city, from east to west, recording many of the varied social and cultural patterns that exist within the city’s naturally defined boundaries.

Ponderosa Pine, Angeles National Forest.

In terms of trees, the Mount Wilson area is mostly populated by Pine trees and California oaks, both are native to the higher mountain areas of Southern California. As you can see, the texture of the pine bark has an enlarged, almost reptilian texture.

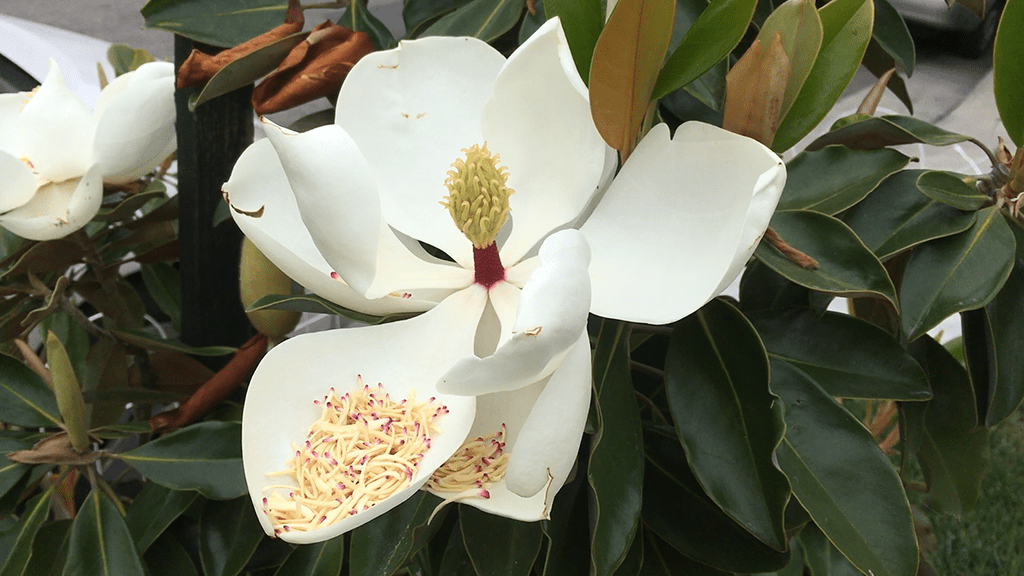

Over the course of the late 19th and 20th centuries, much of the indigenous flora was discarded and replaced with imported, more exotic tree species such as the Jacaranda, Cypress, Magnolia, Eucalyptus, and the infamous Mexican fan palm. Foliage like this defines the cityscape of Los Angeles and the Mexican fan palm, in particular, has become a cinematic symbol of the city. For locals, visits to outlying federally protected forests and deserts allow a nostalgic look back into the land as it once was.

Sedimentary Rock, Angeles National Forest.

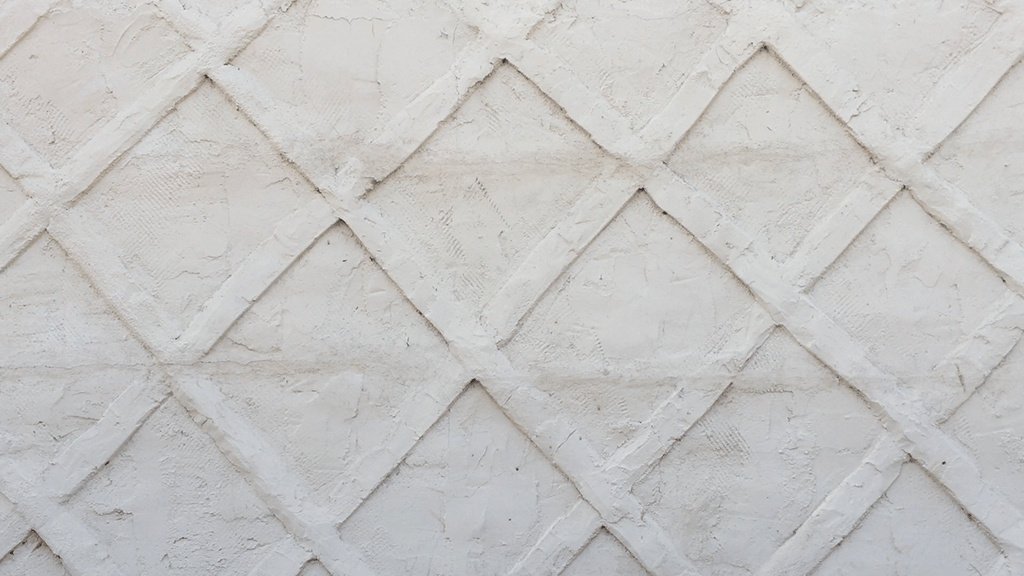

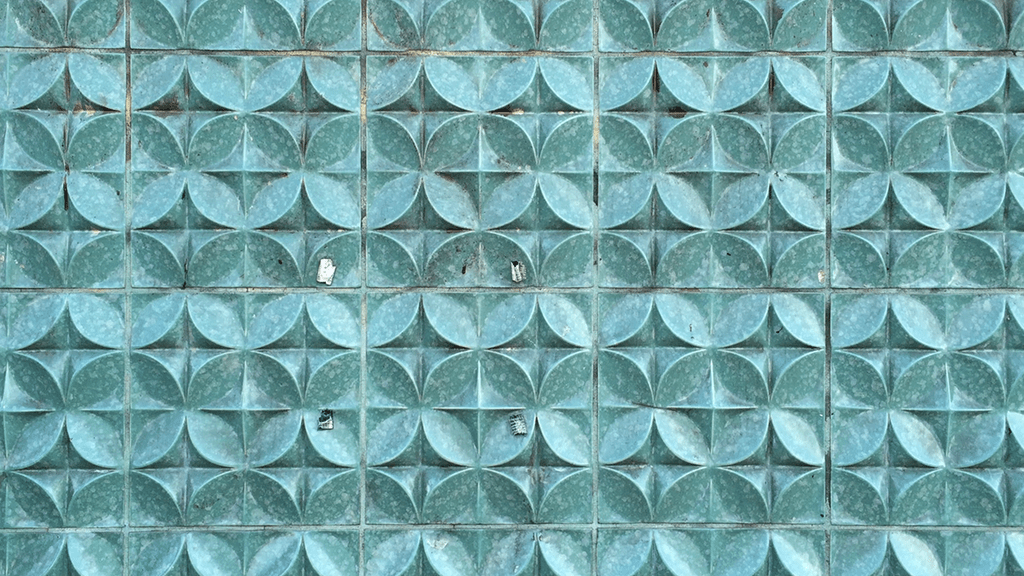

Red Tiles, Chinatown.

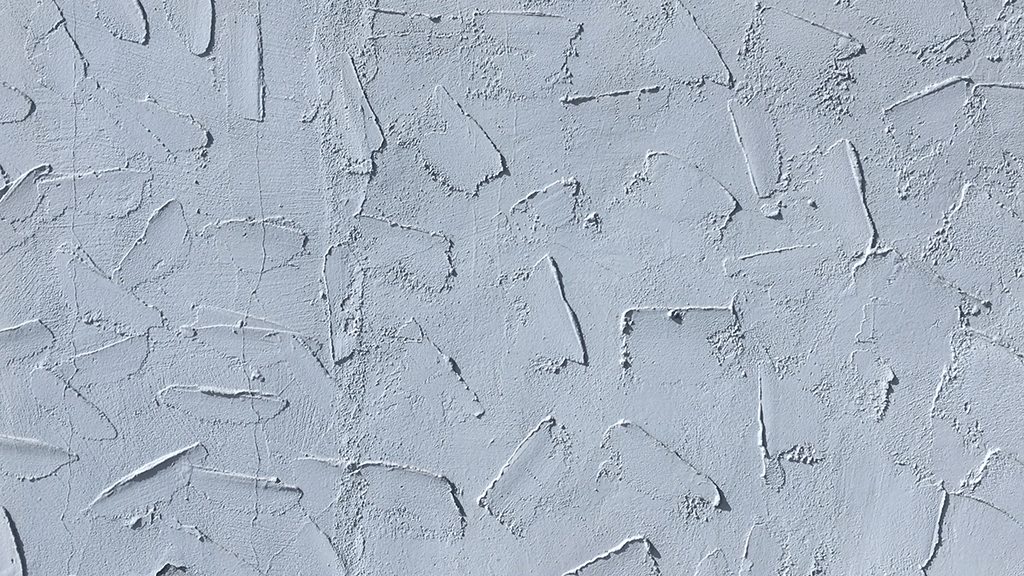

Los Angeles is a city of surfaces and textures, both natural and man-made. They’re found everywhere. Many of the images in Additional Parking are what I call textural referents, they convey the look and feel of the city in the way a resident, and more specifically an artist, might see it. In fact, these shots, be they of bark, stucco, clouds, rocks, sand, brickwork, tiles, foliage, etcetera, all emit discreet and subtle sensations that slowly and collectively amount to a sense of place, perhaps even time. They are tiny building blocks of indirect communication.

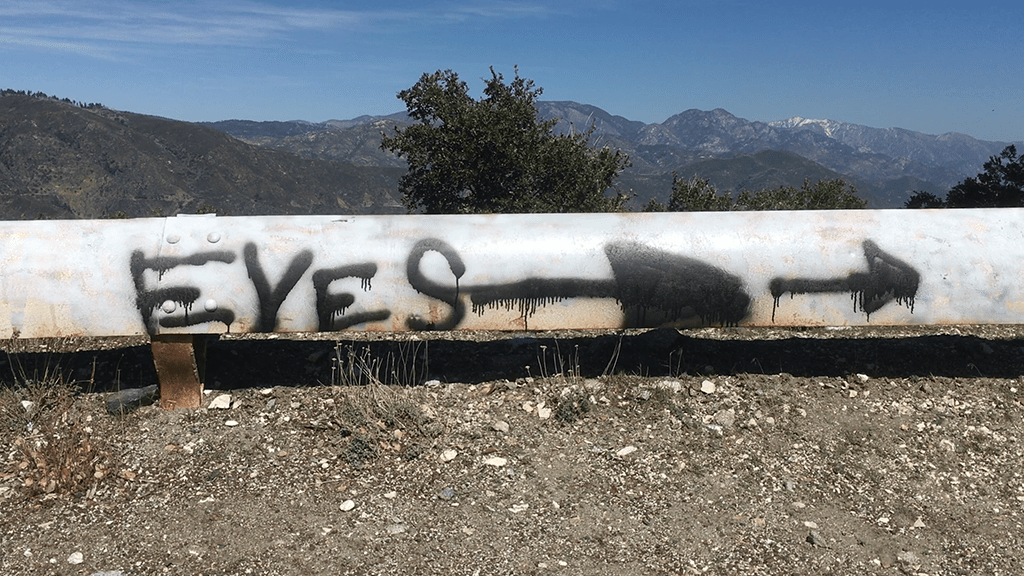

Eyes, Angeles National Forest.

Lookout, Mount Wilson Observatory.

This image calls to mind Caspar David Friedrich’s painting Der Wanderer über dem Nebelmeer. At first, it evokes some of the same romantic delights of the sublime but it could also be viewed in more Dante-esque terms. Setting modern hikers upon the edge of the mountain, they appear as angels in contemplation of a seemingly vast and terrifying abyss.

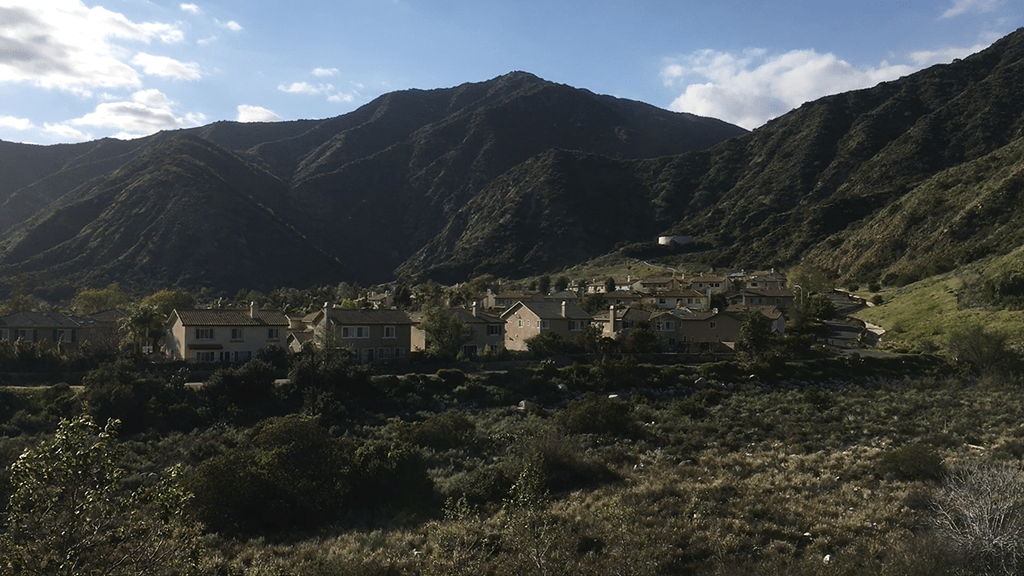

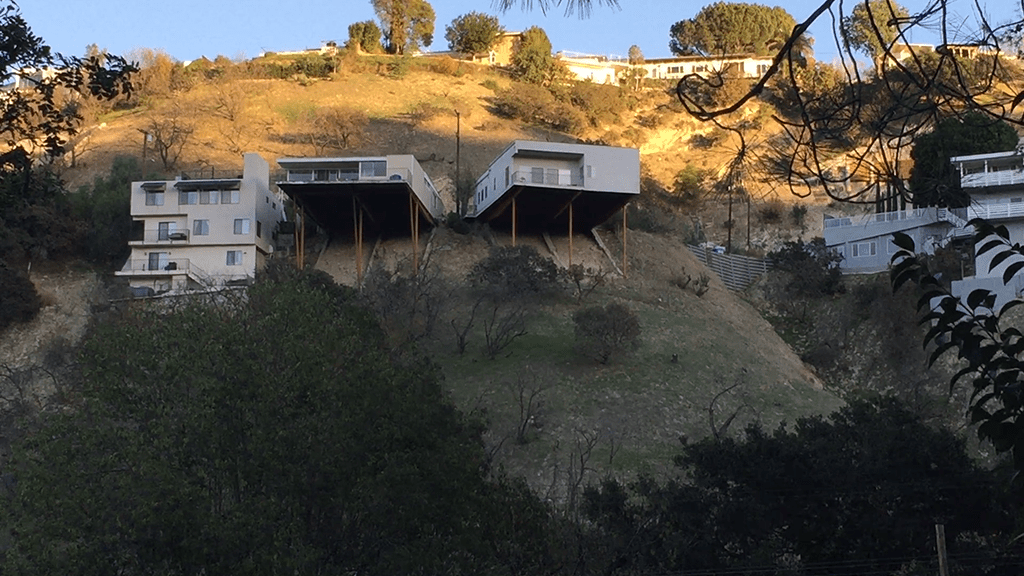

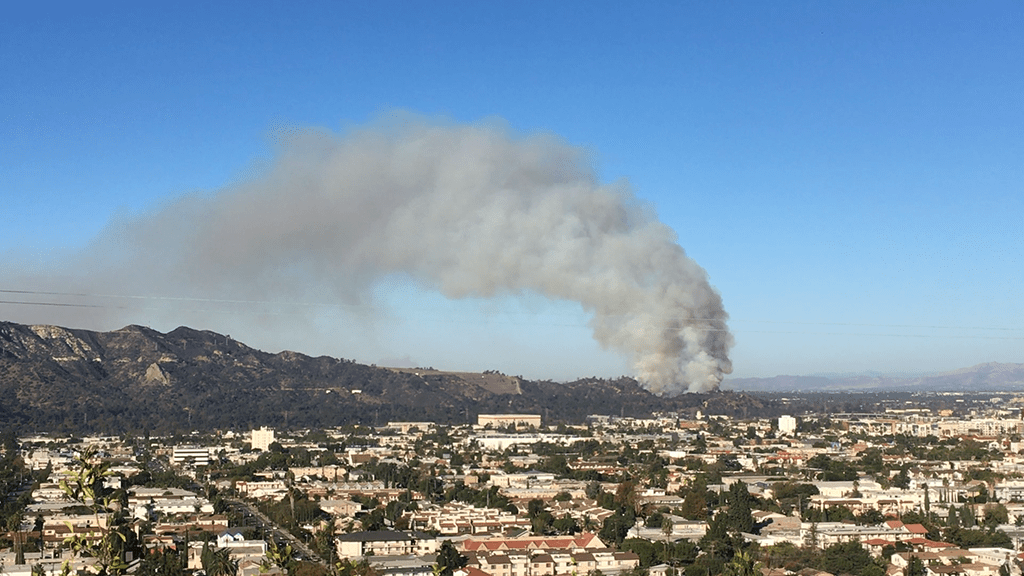

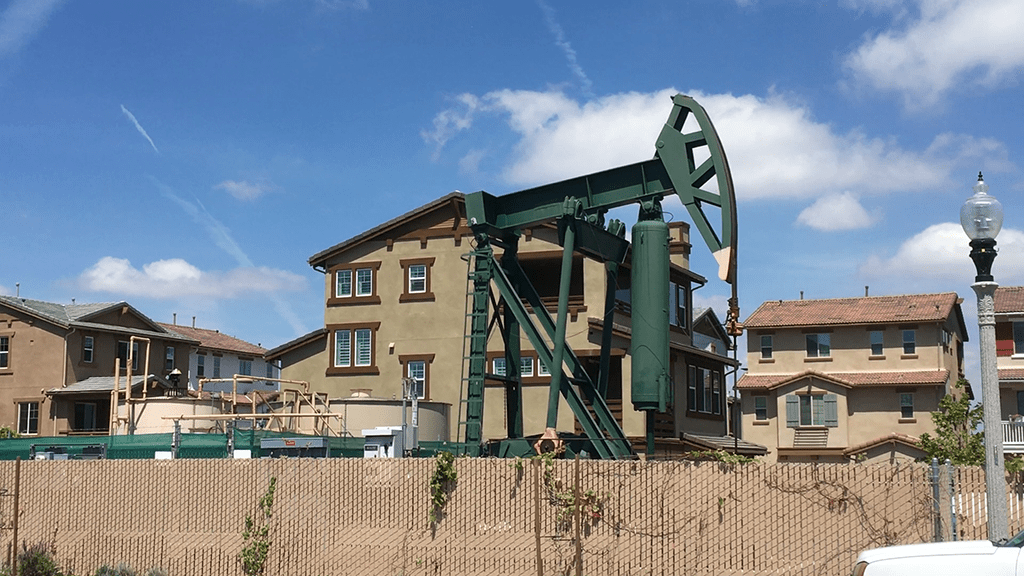

New Homes, Azusa.

A small community northeast of Los Angeles pushing up against the rise of the San Gabriel Mountains, Azusa is one of the many foothill communities that run along the edge of this natural barrier. Like those who live in coastal communities, residents of these areas face a persistent set of threats from nature. Bears, mountain lions, and coyotes wander into neighborhoods looking for food, and their interactions with residents provide an unending source of material for local news channels. Wildfires are also a common occurrence along this edge of the metropolis, with continued global warming they seem to get bigger and more terrifying each year. The almost cancerous advance of real estate and urban sprawl is an unending point of conflict between nature and the city.

Ghost Bridge, Atwater Village.

These are the footings for the bridge that once carried the Red Trolley from Silverlake across the Los Angeles River into Atwater Village. Prior to car culture, the trolley was part of Pacific Electric’s massive 1100-mile transit system that covered the city and its surrounding communities from 1901 through 1953. It was recently repurposed to support a pedestrian bridge that connects Atwater with a bike path that runs along the 5 freeway.

Hermes, Highland Park.

Golden Eagle, South Gate.

Acacia Redolens, La Cañada Flintridge.

Popcorn Cassia, Mid-City.

Common Catalpa, Los Feliz.

Hawaiian Hibiscus, Pasadena.

Martha Washington Geranium, Westwood.

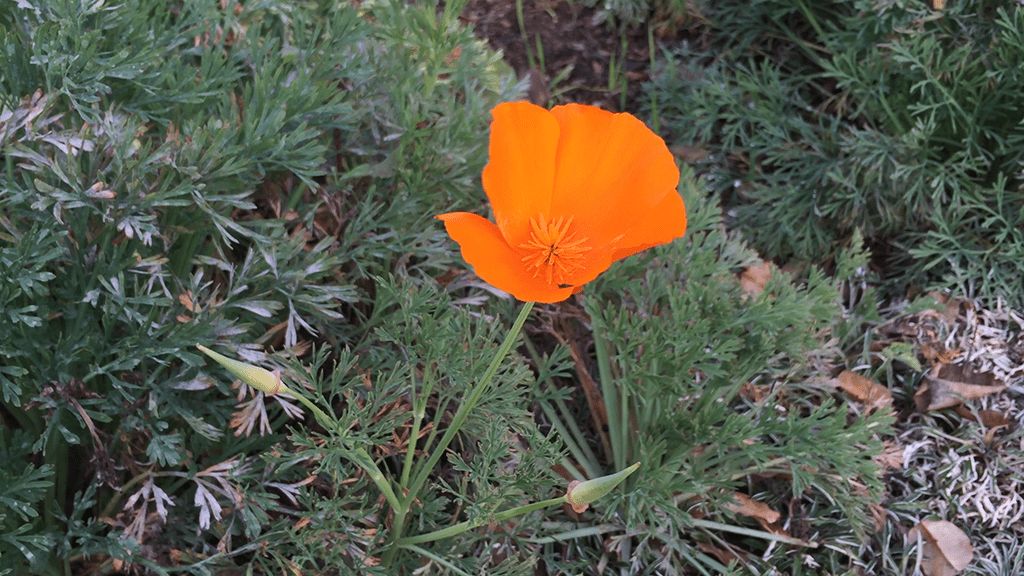

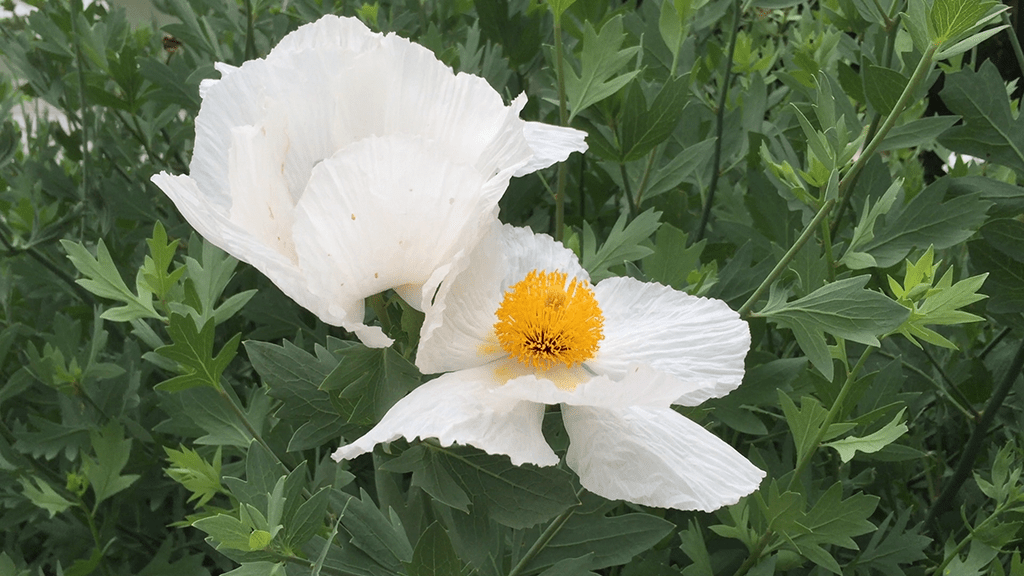

California Poppy, Glassell Par.

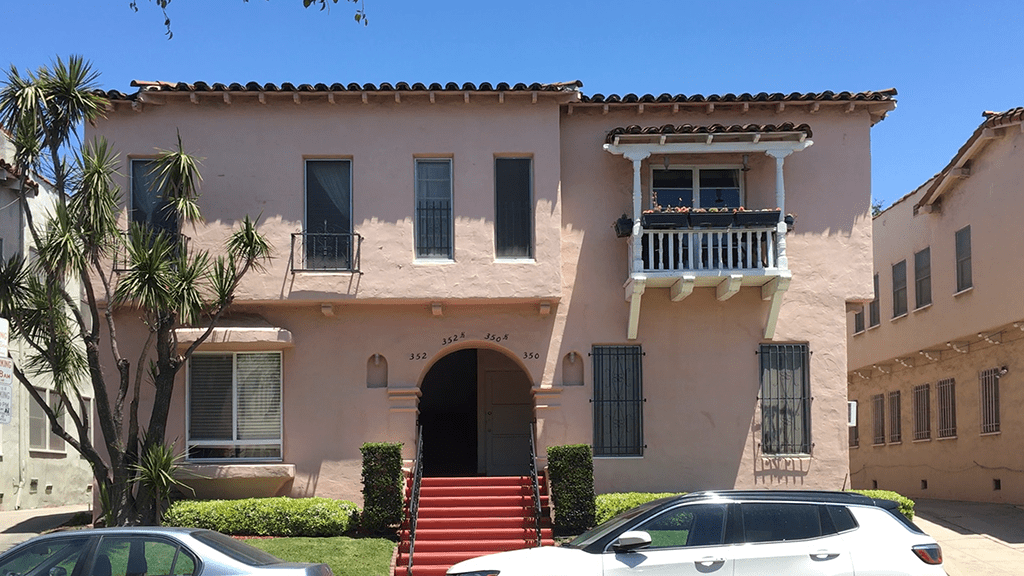

Apartments, Atwater Village.

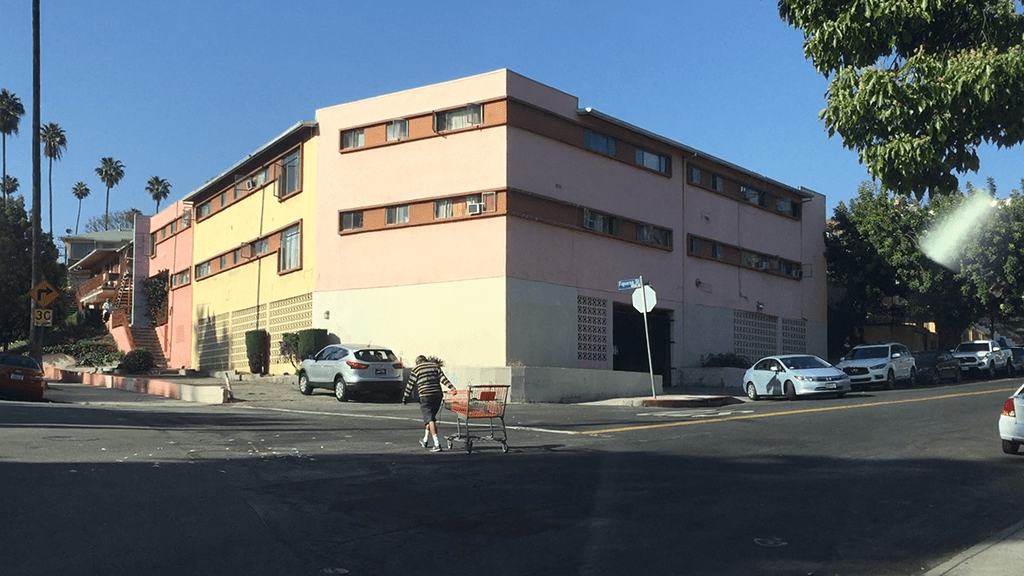

Fosters Freeze, Atwater Village.

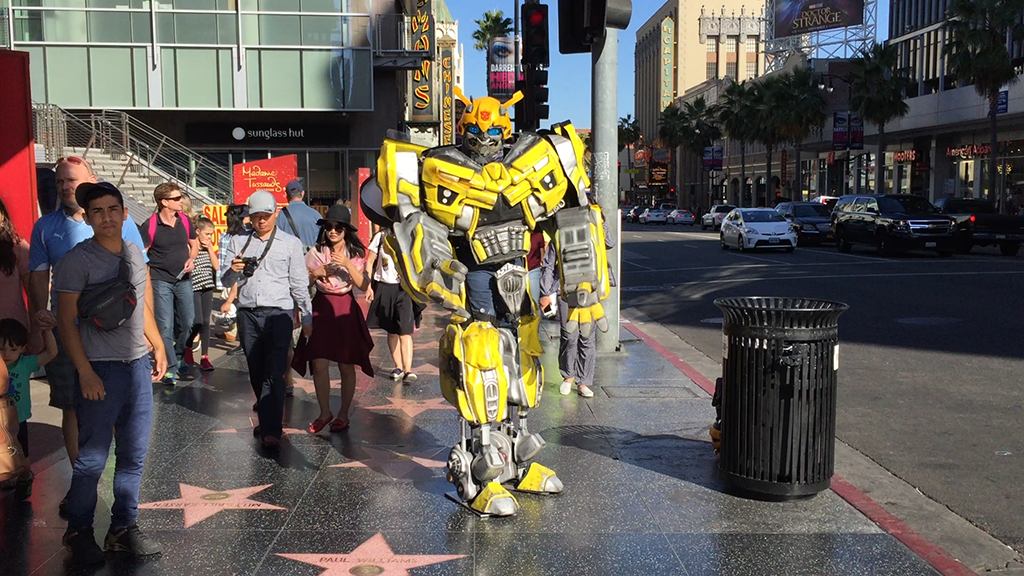

Thom Anderson’s great film Los Angeles Plays Itself discusses at length the complex relationship that the city has with the film industry. Much of his argument revolves around how Hollywood sees the city as a series of stages and props for the endless production of fantasy stories. However, and because of this, moving around the city can generate a constant sense of déjà vu. Residents of Los Angeles are always negotiating and mixing up a real sense of the city with the fantasies created by film and television.

These two images are from Northeast Los Angeles and show locations that were used in Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction. One is a Foster’s Freeze hamburger stand and the other is an apartment building across the street. Both are shown in a sequence that has Butch running over Marsellus with his car as Marsellus, cheeseburgers in hand, recognizes him while crossing the street. When I recognized why I knew this location, it felt a little off-putting. Once you bump into locations like these, they feel similarly fraudulent. Cinema, as always, can transform and upend any actual sense you might have of a place and leave you with a copy of itself, one that’s altogether unfamiliar. Hollywood films Los Angeles and creates a new city, one that’s quite different from the one I live in.

Any descriptive information of place alters it forever. Painting and written language have done this for centuries, providing metaphoric transformations of lands often far removed. Photography and film, the new(ish) kids on the block, provide us with depictions so closely related to the original that we are often given the false impression that they are that very place. They are mediums that not only describe but, in our minds, misleadingly identify. The altercation between description and identification is one of the distinguishing keystones to life in Los Angeles. Unlike any other major city, the physical identity of Los Angeles has been lost in a myriad of fantasies that have been produced within it. That’s not to say that there isn’t an actual cultural identity to Los Angeles, but it has been complicated by the magical dust of Tinseltown altering perceptions of the city’s diverse communities. It is hard to move around the Valley, Beverly Hills, South Central, or even Hollywood for that matter, without the preconceived veneer of filmic clichés altering the way we experience these places.

One of the reasons why Additional Parking was made was because I wanted to film the city without professionally altering it. I wanted to put it together without the chemistry and magic that Hollywood engineers, which transforms the city into a delightful consumer fantasy, making it into something other than what we know it to be. To some extent, I wanted to reclaim this Foster’s Freeze location by filming it in an entirely unglamorous manner. I wanted to transform it back into the ordinary place I knew it to be.

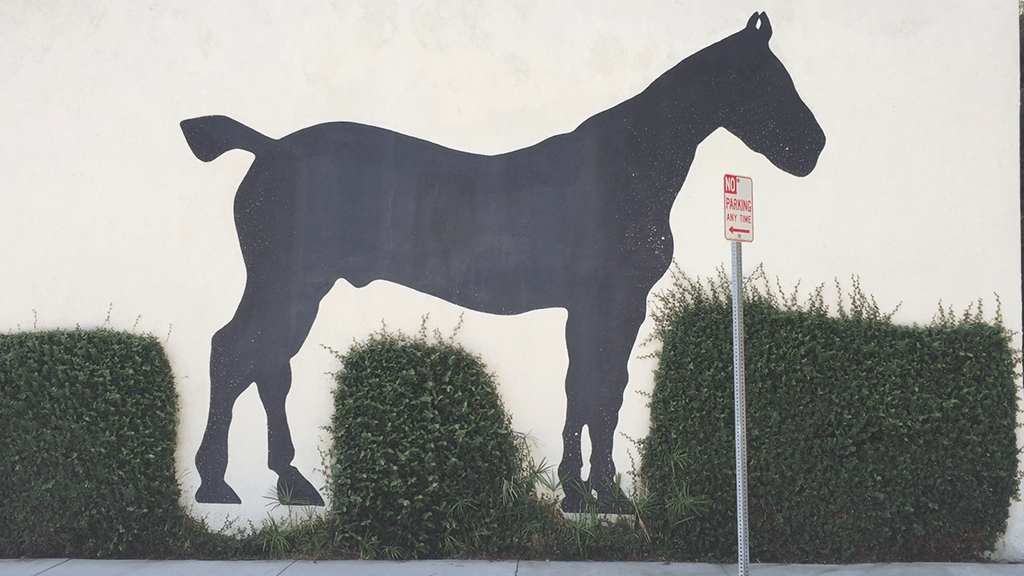

Horse Silhouette, Beachwood Canyon.

Bakery, Glendale.

It goes without saying that Los Angeles is a city that is home to a large number of immigrant communities from all over the world. I’ve heard it stated that the largest population of Koreans outside of Seoul is in Los Angeles, and that the largest population of Armenians outside of Armenia is also in Los Angeles. The city is so vast that there may be several geographical clusters of a particular immigrant community throughout the city. While Little Armenia is in East Hollywood, it’s often joked that big Armenia is actually the entire city of Glendale. Members of the Armenian community in Los Angeles are also from all over the world. In the early 20th century the Ottoman Empire’s genocide of Armenians forced hundreds of thousands to flee Armenia and relocate to different countries. The majority of the diaspora was spread through Russia, France, Argentina, Lebanon, Syria, Iran, Canada, Ukraine, Greece, Australia, and the United States.1

Eventually, many of those émigrés — or their children — relocated a second time to the United States. They brought Armenian culture with them but also some of the influences, particularly culinary ones, that occurred in the countries they had initially fled to. One of my favorite restaurants in Glendale is Greek-Armenian and it serves food that is mostly Armenian, but that is also a unique and delicious blend of both cultures. In Glendale one can find Russian-Armenian, Iranian-Armenian and Syrian-Armenian restaurants that trace the footprints of Armenian displacement and movement.

This image is of a Persian/Armenian bakery in Glendale. The writing is in Farsi, which I don’t read, but when I showed the image to some Iranian friends of mine they giggled a little. I asked them why and they replied that the bakery is named after a particular kind of commercialized treat that they remember eating as children. They felt it was funny to name a bakery after it. It made me think of Proust’s madeleine conjuring fond memories of childhood and all its comforts.

1 “Armenian Genocide.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 14 Feb. 2024.

Cruiser, Hollywood.

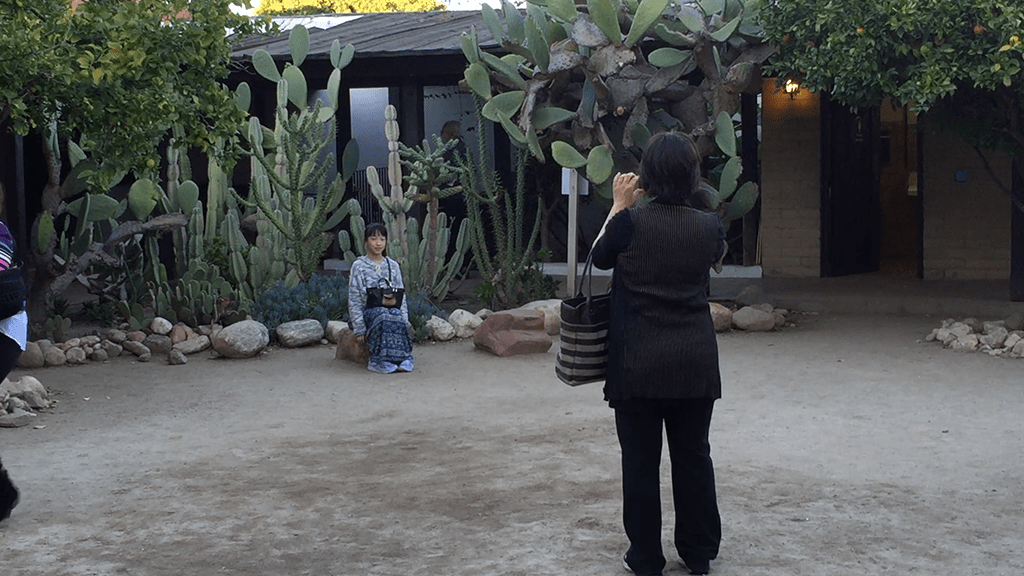

Faces, Various Locations.

Faces, Various Locations.

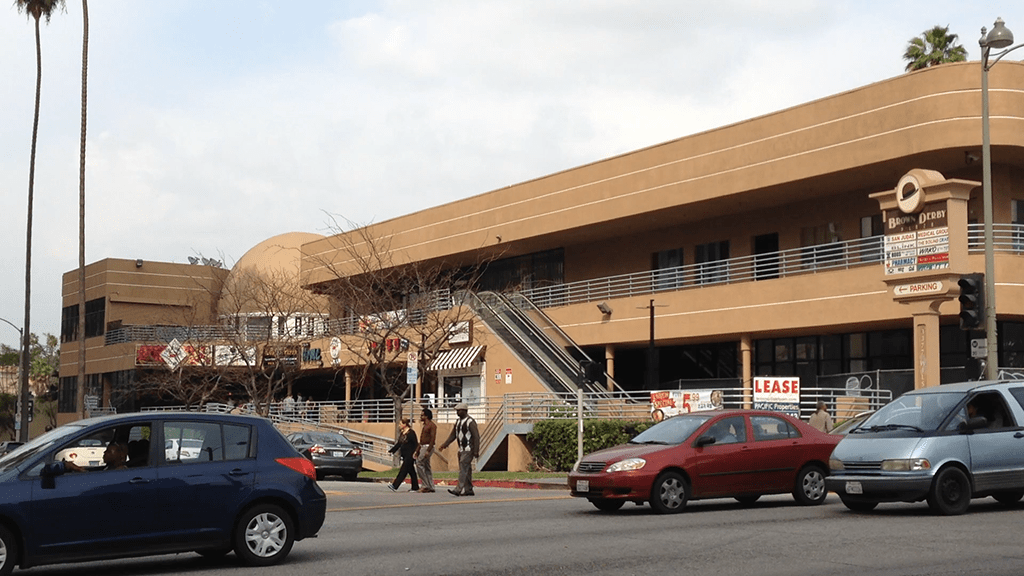

Mini Mall, Koreatown.

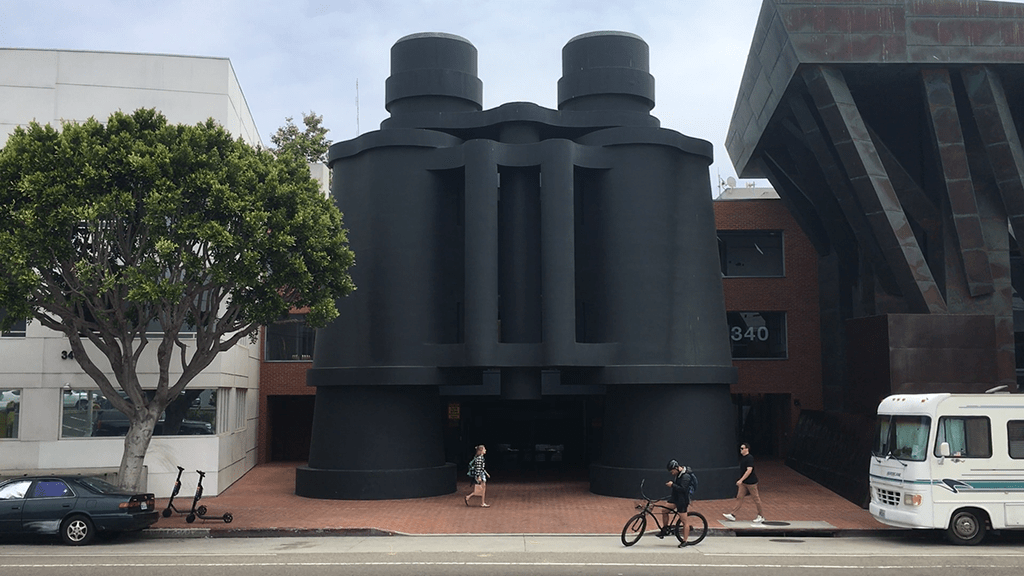

Opened in 1926, the Brown Derby was a restaurant on Wilshire Boulevard shaped like an oversized derby hat. It’s no longer there but I’ve heard stories that the original Derby got painted silver and was stuck inside of a shopping mall somewhere out in the San Fernando Valley. There are other mysterious rumors about the somewhat nomadic existence of this architectural object, but I do know for sure that the original location was bulldozed and turned into a parking lot.2

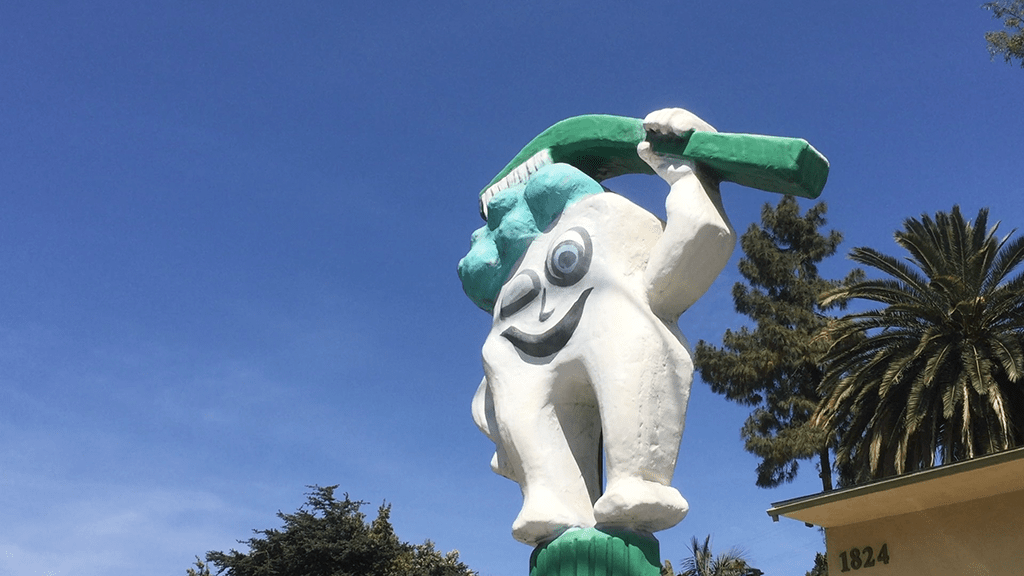

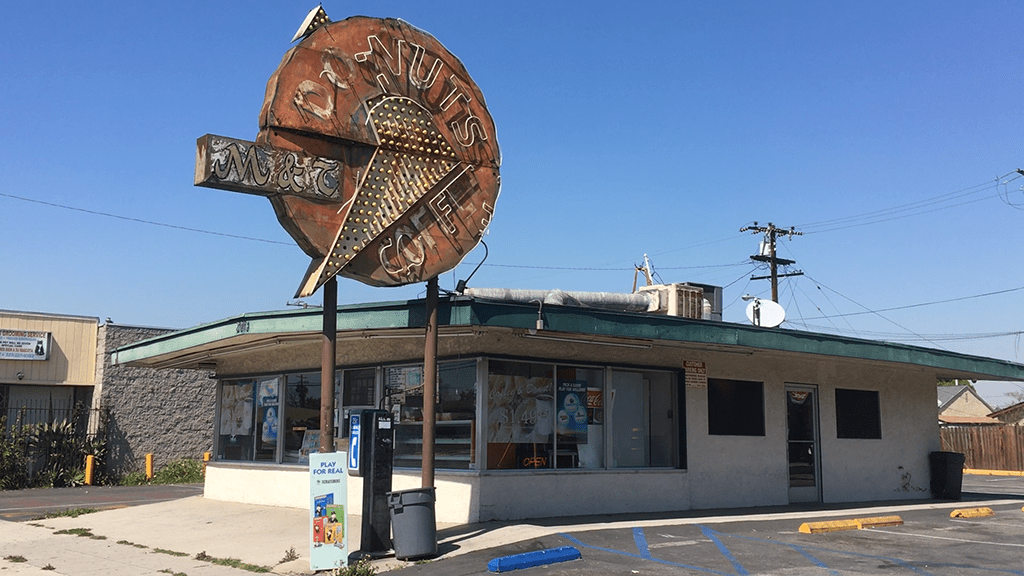

It is unclear where this kind of architectural idea — buildings shaped like objects — found its start, but it made its way to Los Angeles a long time ago. A hot dog stand shaped like a hot dog in a bun, or a donut/bagel store with an oversized donut or bagel on its roof. I’ve even seen a mobile shoe repair car that was shaped like a boot. I suppose Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown came up with a reasonable hypothesis about why a duck-shaped building should be as such but, ultimately, it just boils down to sales gimmicks designed to attract customers. And it does work. An Oscar Mayer Wienermobile, a car shaped like a hot dog in a bun, stopped by my street once and it seemed like the entire neighborhood shut down for the day.

This image shows another unremarkable Los Angeles’ mini-mall, complete with a vague allusion to a Spanish-styled architectural heritage. However, this is the Brown Derby Plaza which was built on the original location of the restaurant and subsequent parking lot. What makes it different from most mini-malls is the derby dome on the third floor. I first visited the space years ago and what I found inside the dome was a Korean bar. The bar was small and circular, with the center occupied by a fabricated mini-mountain complete with trees, foliage, and tiered shelving for the alcohol served by the bar. To this day, I still don’t quite understand the connection between the mountain and the derby hat but, like many things in Los Angeles, the breakdown of a cohesive symbolic order leaves you feeling perplexed, and yet oddly satisfied. Living in this city, you eventually resign yourself to the idea that not everything is going to make sense. Anyone who attempts to generate too much meaning from all the seemingly disassociated signs will find themselves doomed to suffer a similar fate to Thomas Pynchon’s Oedipa Maas.

2 “Brown Derby.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 16 Jan. 2024.

Bear on the Street, Koreatown.

Concert by the River, Atwater Village.

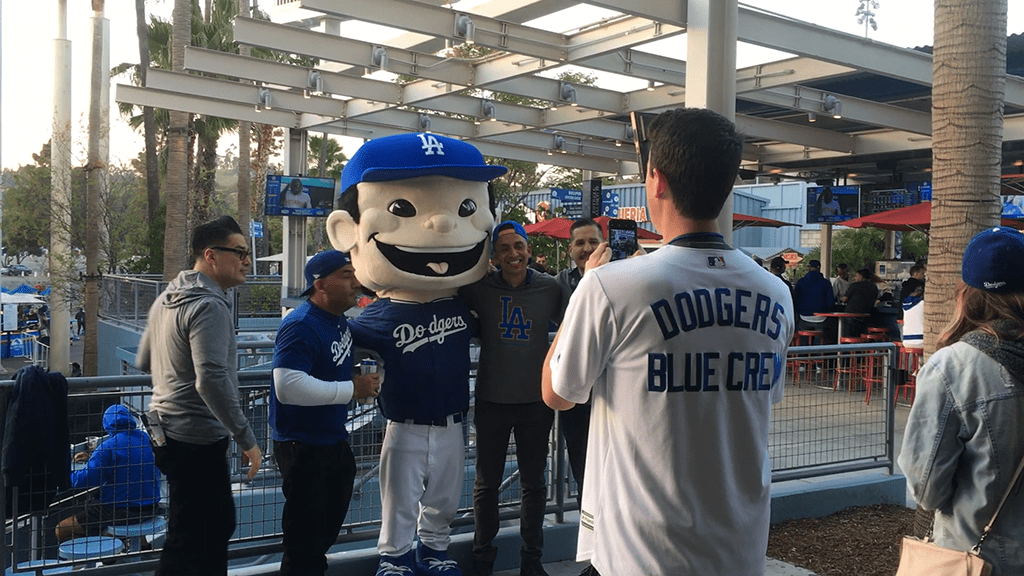

Saint Gregory, Dodger Stadium.

Santana Fan, Eagle Rock Park.

Hidden Bear, Culver City.

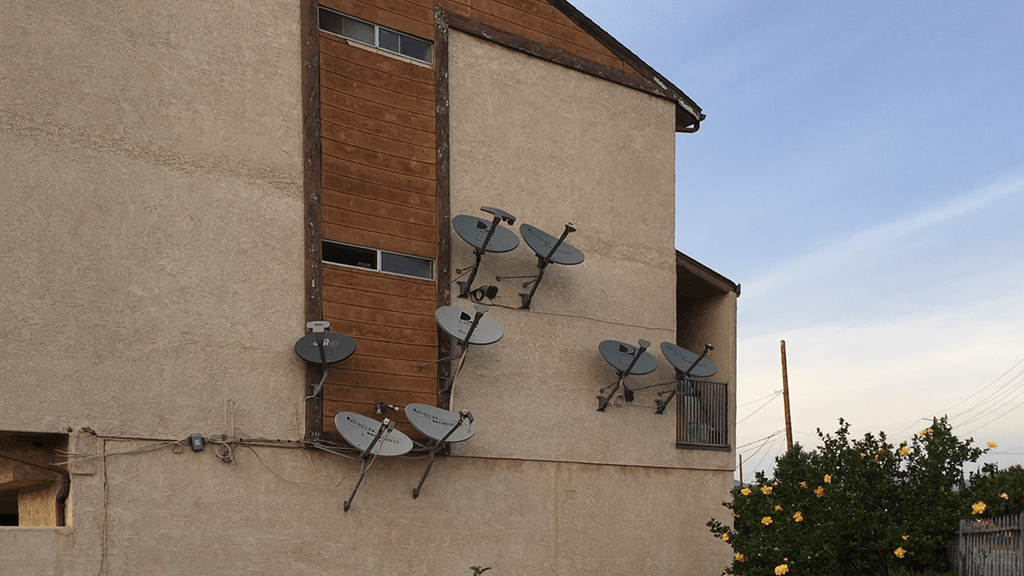

Cable Dishes, Glassell Park.

Late Night Tacos, Highland Park.

Motorhome, South Central.

Goal!, Florence.

Air Mattress, Glendale.

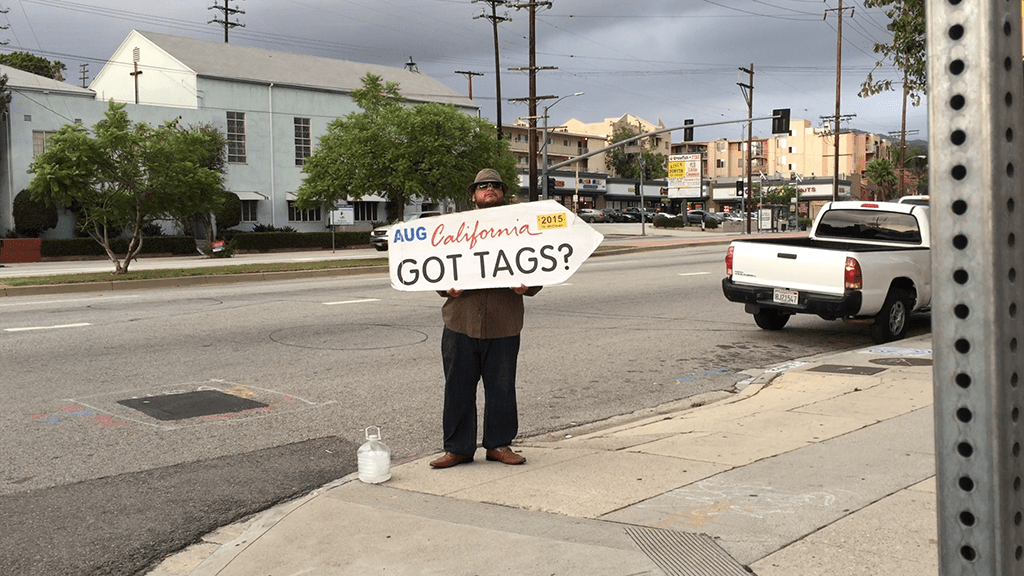

Got Tags, Eagle Rock.

Ancient Air, Highland Park.

Skid Marks, Lennox.

Murals, Florence.

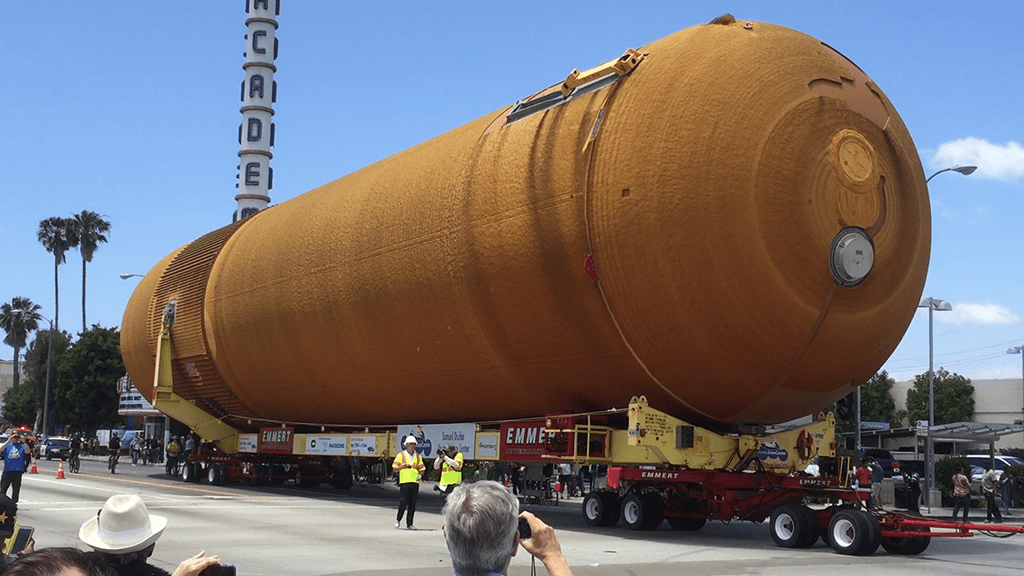

Shuttle Fuel Tank, Morningside Park.

Market, Compton.

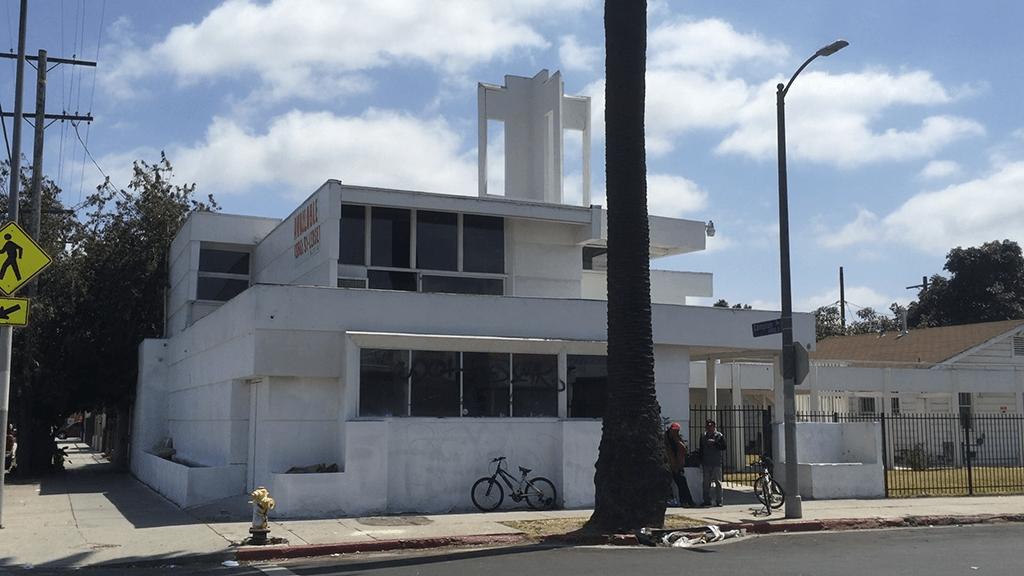

Bethlehem Baptist Church, South Los Angeles.

Designed and built by Rudolph Schindler in 1944, this building was paid for and occupied by a small African-American congregation until the 1970s. The group might have chosen Schindler, an Austrian immigrant, because he was inexpensive and his design ideas were innovative and different. The original congregation moved to a larger building and sold the church to a female minister who occupied the space into the 2000’s, until she had to vacate it to deal with some medical issues. From then on, it seems the church was shuffled in and out of various nefarious ownerships until it was repossessed for unpaid back taxes. It was leased to Faith Built International church in 2014, but there was no evidence that they were still there at the time this image was shot. It’s now owned by an investor group who seem to have an understanding of the building’s historic value and, accordingly, want to sell it to the highest bidder.3

I found the church almost by accident while riding around the area. It was in bad shape, almost derelict, though much of the graffiti had been covered in a recent thin coat of paint in an effort to enhance its selling potential — a ‘for rent’ banner was posted on the side of the building. I had a chat with some men who were splitting a few lunchtime beers out front, but they didn’t have any information about what it looked like on the inside, or if any recent tenants had occupied the space.

Los Angeles has a short memory when it comes to architecture and history. Preservation and conservation are small obstacles to the frenzied real estate development of the city. Los Angeles is a city that seems to be in a near-constant state of architectural transition. There are many small hidden gems like this Schindler building tucked into the folds of the city’s space and time. A lot of buildings get bulldozed and disappear before anyone even notices. This was true of Richard Neutra’s Maslon House in Rancho Mirage, now only a memory. The application for a demolition permit was submitted and granted on the same day. The house was erased within a week. What’s really odd is that this kind of thing barely raises an eyebrow in Southern California. Los Angeles construction and development permits seem to be handed out with little red tape, review, or bureaucracy. The Bethlehem Baptist Church is registered as a Historic-Cultural Monument, but with little or no interest in its restoration, its future seems unclear.

3 Barragan, Bianca. “14 Shocking New Facts About South LA’s Landmark Rudolph Schindler Church.” Curbed Los Angeles, 3 Feb. 2016.

[CLICK ON THE RED MARKER TO VIEW VIDEO]

Oak Tree Church, Koreatown.

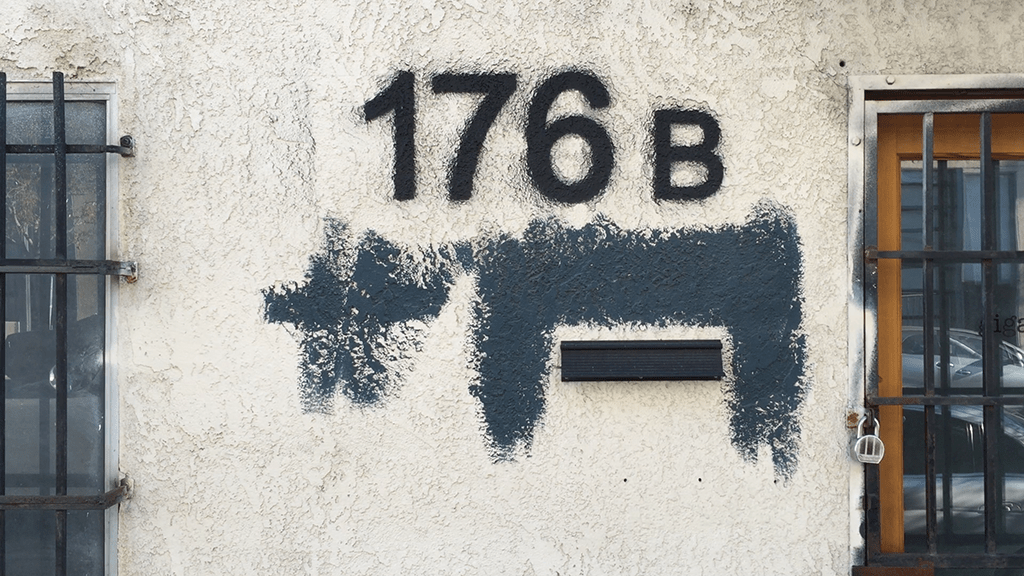

Mail Dog, Lincoln Heights.

Dead Bird, Glassell Park.

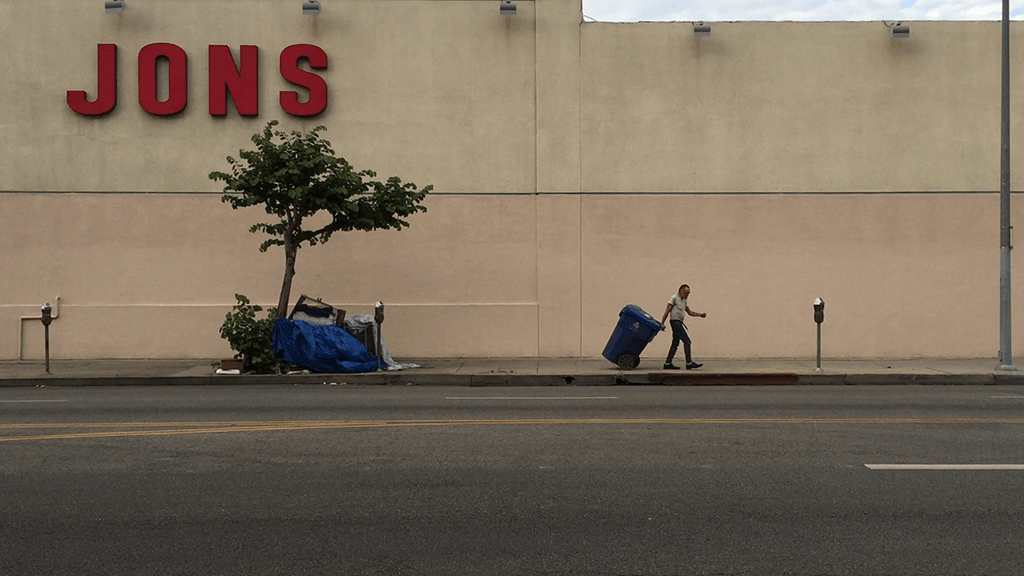

Jons, East Hollywood.

Low Riding, Los Feliz.

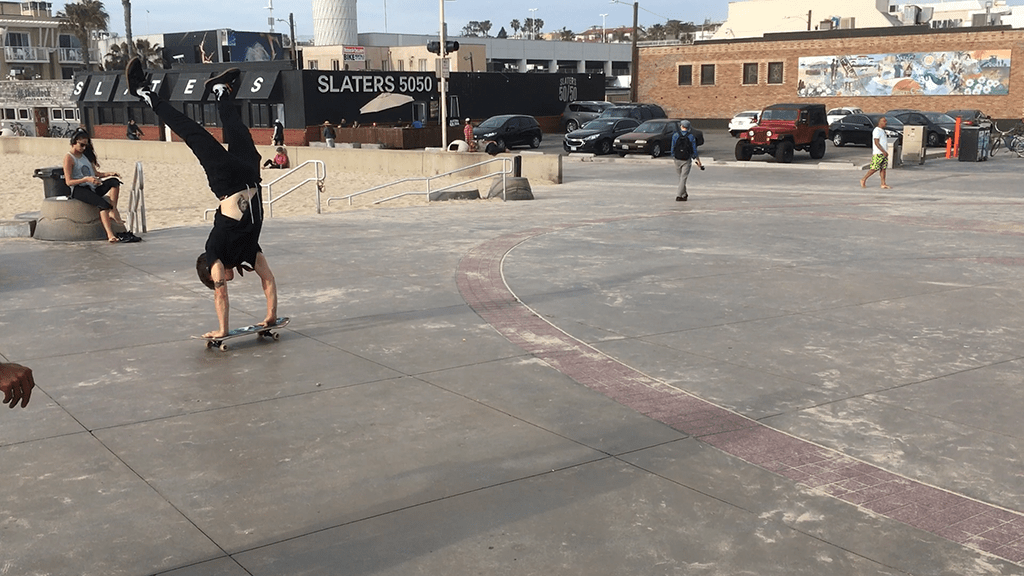

Skater, Melrose Hill.

Underpainting, Central Alameda.

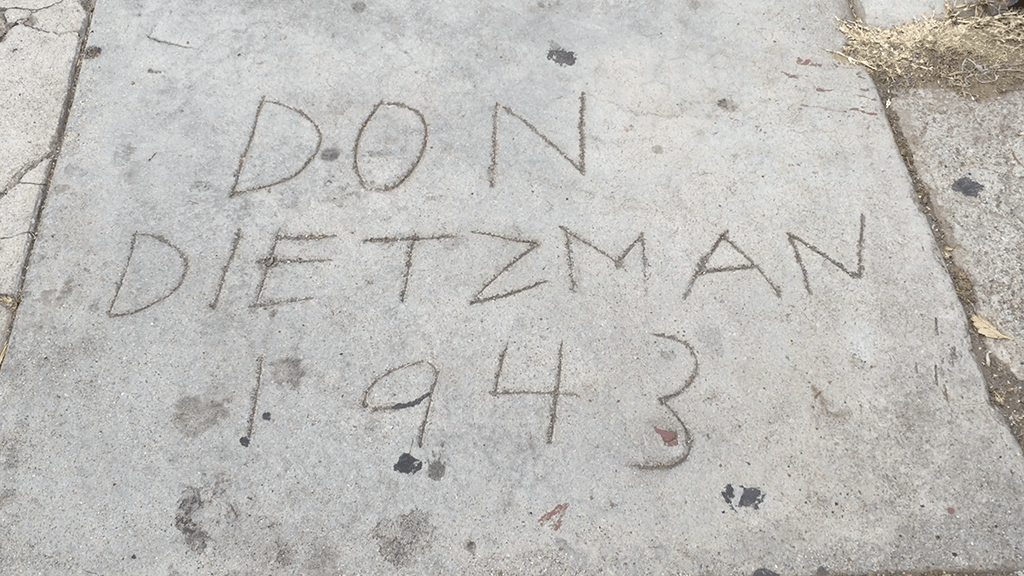

El Osito, Lincoln Heights.

Boyle Heights was named after Andrew Boyle, an Irishman who around 1858 purchased and owned most of the bluff the land sits upon. It has traditionally been home to a fairly diverse population of incoming ethnic groups. Many Japanese immigrants, with an established community in Little Tokyo, extended and moved east into Boyle Heights in the early 20th century. Large Jewish and Mexican immigrant communities also made the area home throughout the 1960’s. Because of redlining — racial banking practices — and the construction of several freeways that landlocked the area, a lot of things changed during that time. The 5, 10, 60, and 101 freeways all intersect and border the neighborhood. Today, Boyle Heights is 94% Latino and considered a stronghold of Mexican-American culture, its community actively protesting change and gentrification.4

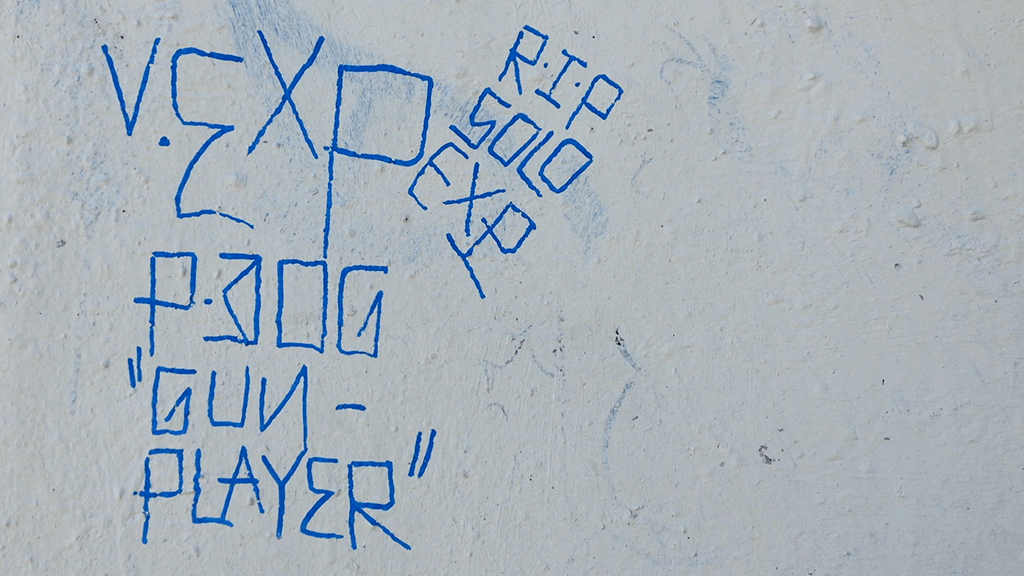

In English, El Osito translates to The Little Bear. It seems he was a part of the White Fence gang. White Fence is not only the oldest gang in Los Angeles, but it is also one of the largest and most violent gangs in the city’s history. It started out in the early 20th century in Boyle Heights as a sports team associated with La Purisima Church. It’s said the name originates from a white picket fence that surrounded the property, also thought to be a symbolic barrier between the Latino community and other residents of the area.5

The cement inscription on the sidewalk was shot in Lincoln Heights, an adjacent neighborhood that is considered Los Angeles’s first official suburb. Lincoln Heights is a neighborhood that somehow has managed to be forgotten by the rest of the city. Walking around the hills there is like stepping back into an older, more rustic and less material, Los Angeles. I imagine it’s what most of the city looked like in the 1920’s. Lincoln Heights, also home to a predominantly Latino population, is home to The Avenues, a splinter gang of White Fence origins that also has a long and sorted history in the city. El Osito’s cement markings may have been a kind of “fuck you” to an offshoot gang back in 1977. Like many things in Lincoln Heights, the inscription has stuck around.

4 “Boyle Heights, Los Angeles.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 14 Feb. 2024

5 “White Fence.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 19 Sept. 2023

Park Plaza, Los Feliz.

Northbound 2, Eagle Rock.

Southbound 2, Eagle Rock.

Watermelon, MacArthur Park.

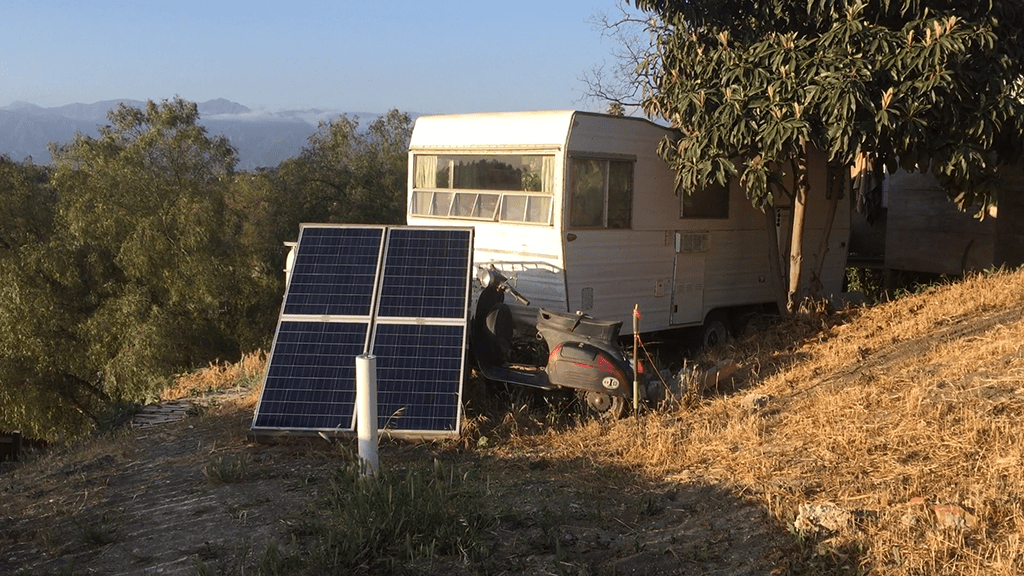

CalEarth, Hesperia.

The CalEarth Institute was founded by Iranian-American architect Nader Khalili in 1991. The institute was created to develop housing that was sustainable, affordable, and easy to build, particularly in impoverished areas of the world. The institute was also created to educate young architects in the various kinds of low-cost construction techniques created by CalEarth.6

In the foreground of this image, some of the housing prototypes can be seen in various states of construction and decay. In the background, you see the encroachment of Los Angeles’s suburban sprawl encroaching upon the high desert. How strange and oddly beautiful it is to see the contrast in these differing philosophical approaches to housing.

6 “Our Founder.” CalEarth, http://www.calearth.org/our-founder

Sad Bear, Glendale.

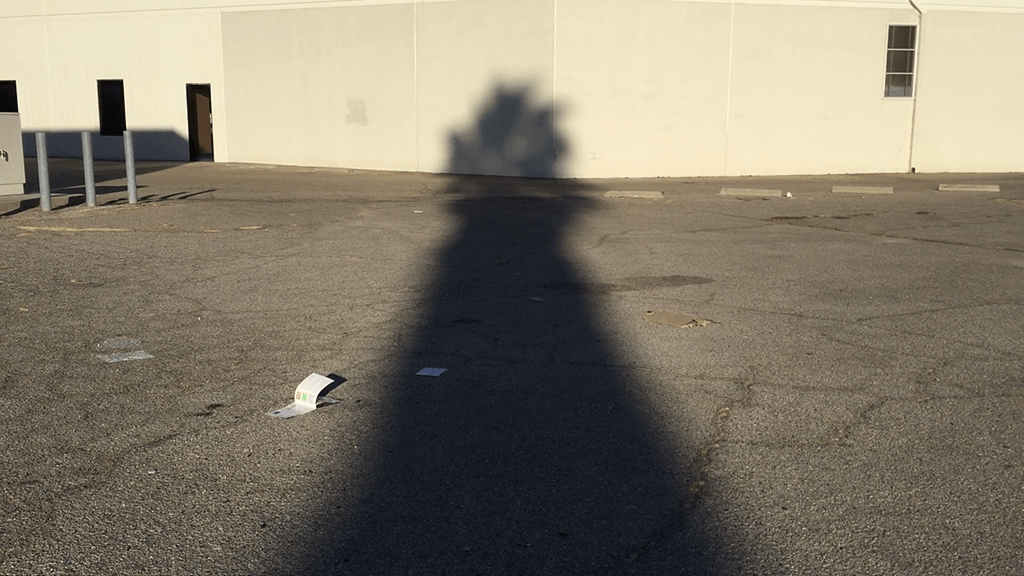

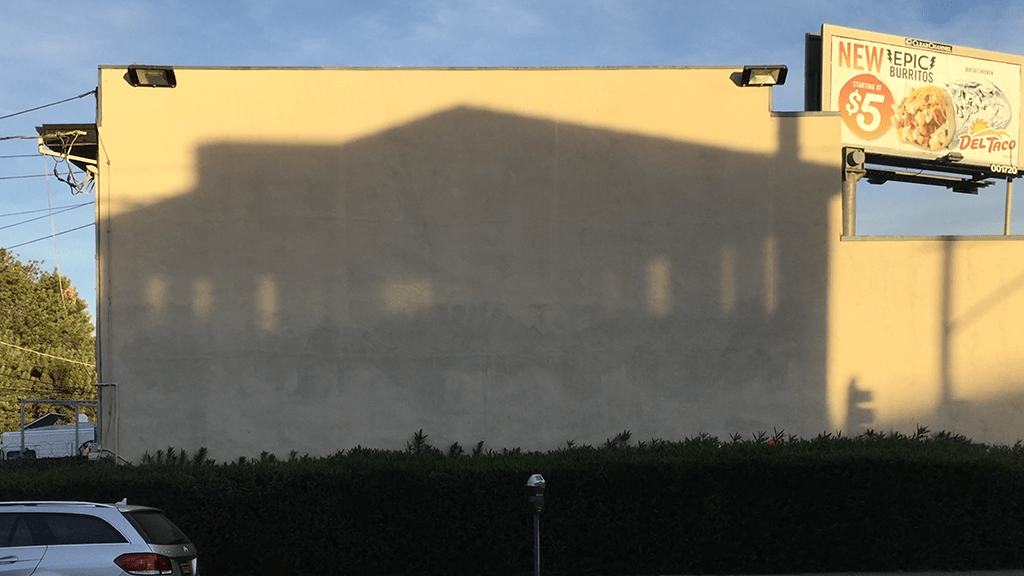

Palm Shadow, University Park.

Flipper, Malibu State Park.

Tiny Horse, Burbank.

Horse Walker, Burbank.

Horse Crosswalk, Burbank.

Hayworth ARMS, Fairfax District.

Most commercial buildings will carry a name to tell people something about the kind of business done there, or about the origins and history of the building. New York has many such places, like the Chrysler Building and the Woolworth Building. Los Angeles has a few too, The Bradbury Building, Walt Disney Concert Hall, and the Capitol Records building. This system works for commercial buildings, for the most part, but when it comes to residential buildings, the naming and labeling of apartments can take on an entirely different logic.

It is in no way unique to Los Angeles but, given the multitude of architectural vernaculars of the city, there are a broader range of imaginative vacancies to fill. An apartment building’s name —descriptive words or phrases used to describe shared housing — should provide a sense of place, character, or prestige, to entice and seduce potential renters. The most common term for this is buyer bait, and this phrase more or less summarizes the singular reason for giving any apartment building a name. They can also come with fancy descriptors, some of the most common here in Southern California are: Manor, Chez, Château and, of course, Arms.

The Hayworth Arms apartments is typical of many similar buildings of its time. Reyner Banham described — or better said, decried — this particular kind of Los Angeles building in his seminal book written in 1971, Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies, referring to it as a Dingbat, a two-story walk-up Mid-century modern building that typically has parking covered by an overhang. Banham used the phrase primitive modern to set them apart from more serious modern buildings by known architects like Richard Neutra and Oscar Schindler.

In looking for a historical precedent for the name, a cursory search of the internet first hit upon Haworth Arms, an obscure old pub in England with a slightly different spelling. A more likely inspiration for its name was Rita Hayworth. She does not comes to mind at all when looking at this building, but I suppose the developers thought a little of her celebrity sheen could help put a touch of Hollywood sparkle on the Hayworth Arms.

These buildings are now charming, quaint, very desirable, and ripe for demolition. In the central city, they sit upon plots of land that can be developed vertically and more densely. The Mid-City area is undergoing a dramatic revision of the urban plan laid out in the 20th century. This seems to have come about in an effort to accommodate the unending influx of people moving into the city to chase their Hollywood dreams of fame and fortune, much like Rita Hayworth did during her time.

Circus Liquor, North Hollywood.

Pedestrian, East Hollywood.

Nook, Hollywood.

El Amigo Bar, East Los Angeles.

Farmer John Mural, Vernon.

The brand of processed pork products known as Farmer John has a processing plant in Vernon, a mostly industrial area southeast of downtown Los Angeles. In 1957, Barney Glougherty, the initial owner of Farmer John, hired a Hollywood scene painter by the name of Les Grimes to paint a decorative swine-themed mural around the entire factory compound. In total, the Hog Heaven mural is 30,000 square feet and it took just over a decade to paint. Grimes was accidentally killed on the job when he fell to his death from the scaffolding he had used to paint higher parts of the buildings. Arno Jordan was hired to complete the work.7

Vernon is now a far cry from the modest and bucolic roots of a town that, in the late 19th century, was known as a retreat from the Wild West debauchery of central Los Angeles. It boasted beautiful suburban homes, a 10-acre central park, and wonderful farmland that was perhaps much like the mural on the Farmer John plant.8 Today’s Vernon is not a part of town that you would ever find on a tourist map. As of the 2010 census, the city’s population was 112 residents. It’s an area that is dominated by all kinds of industrial buildings, particularly meatpacking businesses. Its streets are filled with trucks bringing in livestock and taking out product. The city has been threatened with disincorporation from Los Angeles because of political and economic corruption stemming from a lack of corporate transparency in regards to city management. Overall, Vernon is a grim and depressing place.

The mural, despite its strangeness, is quite a sight to behold. It depicts the illusion of a rural pig utopia with plenty of grassy fields, shady trees, running streams and odd pig activities —populated by farmers and happy pigs. Antonioni tried to capture it in his 1970 film Zabriskie Point, but it seems to gets lost in the larger narrative of the movie. I love this particular shot because a bus stop and an actual tree participate in the trompe l’oeil of the mural itself. There is much more to see, and a walk around the plant is necessary to take all of it in. While viewing it, the distinct smell of death in the air is a constant reminder that this is all an illusion, behind these walls something nefarious is afoot.

7 pleasurepalate. “Farmer John’s Hog Wild Mural ~ Vernon.” LA Taco, 31 Dec. 2008, http://www.lataco.com/farmer-johns-hog-wild-mural-vernon

8 Meares, Hadley. “Vernon: The Implausible History of an Industrial Wasteland.” Curbed Los Angeles, 19 May 2017.

9 “Vernon, California.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 29 Oct. 2023.

Snitch, Harvard Heights.

Laundry Day, Harvard Heights.

Jesus Recycles, Florence.

The Mayhart, Rampart Village.

Garbage Day, Cypress Park.

Various Mailboxes, Happy Valley.

Two Lawns (1), West Hills.

Two Lawns (2), Sherman Oaks.

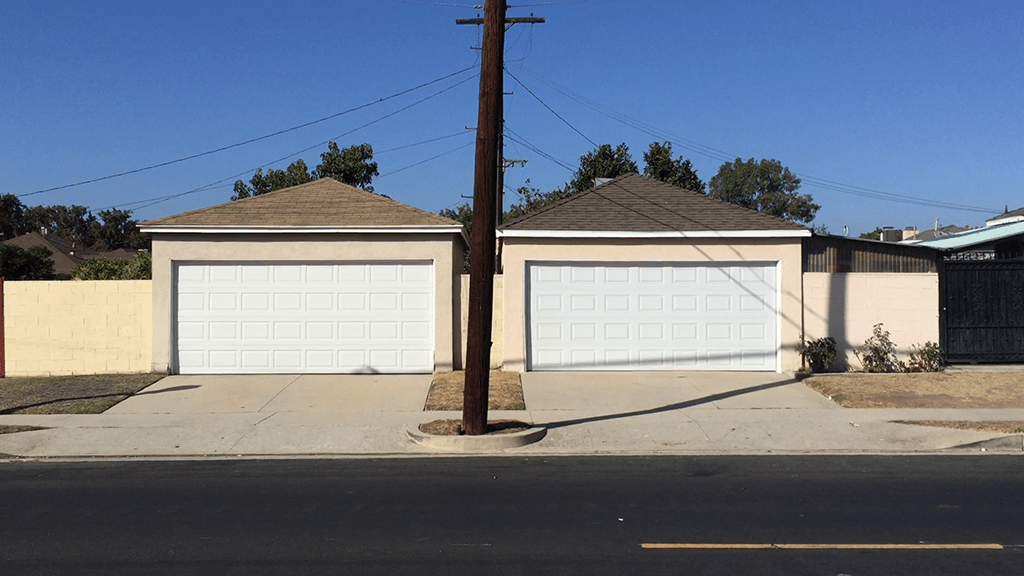

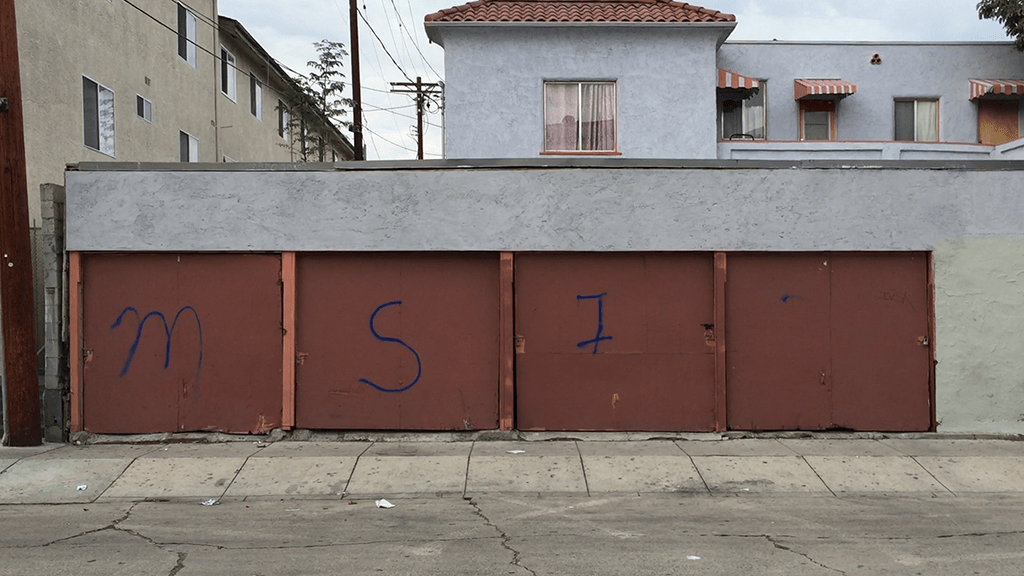

Two Garages (1), Leimert Park.

Two Garages (2), North Hollywood.

Sammy’s Liquors, Jefferson Park.

Free, Glassell Park.

Redaction, Santa Monica.

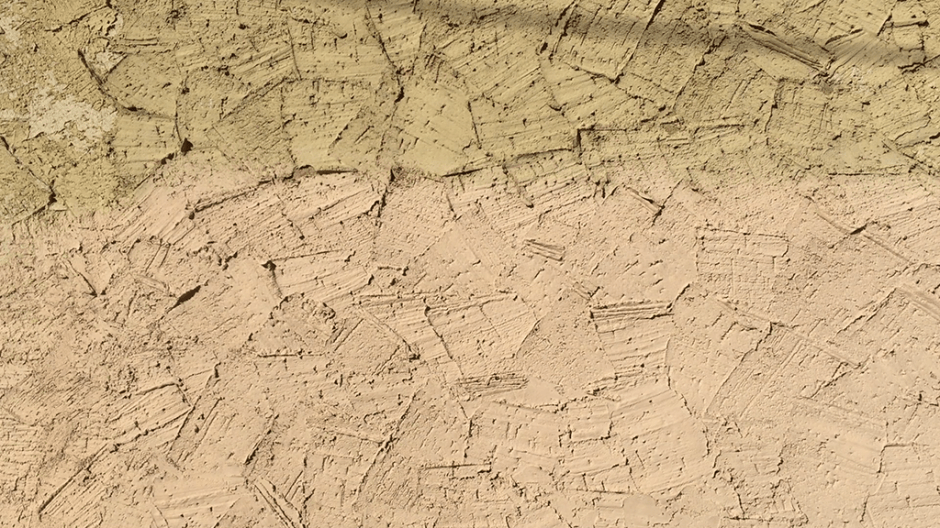

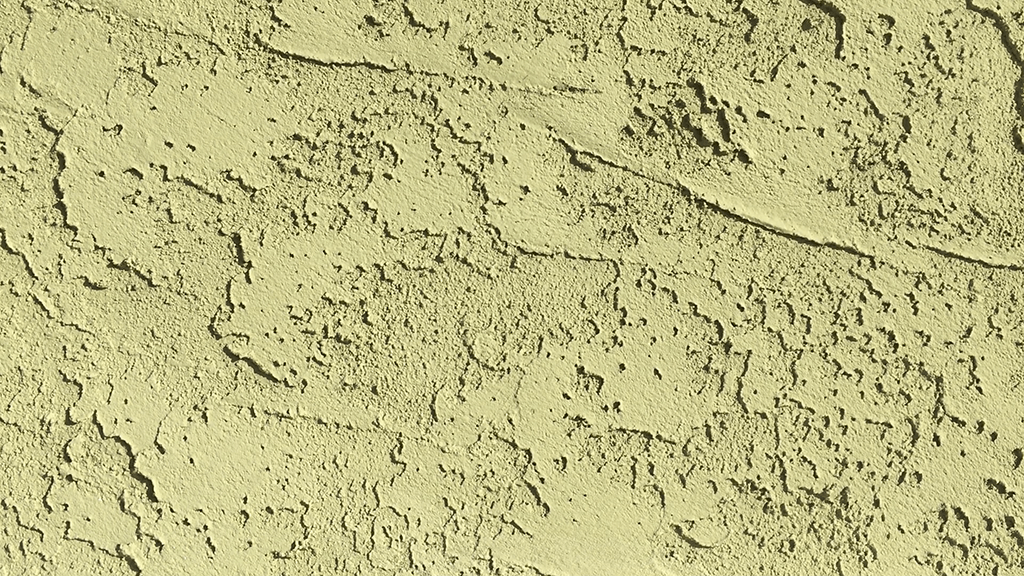

Freestyle Stucco, Hesperia.

Combed Stucco, Hollywood.

Patchy Stucco, Eagle Rock.

Custom Stucco, South Westlake.

Spanish Stucco, Eagle Rock.

Heavy Lace Stucco, Eagle Rock.

English Stucco (variation), South Westlake.

Custom Stucco, Eagle Rock.

Dash Stucco, Highland Park.

English Stucco (variation), Eagle Rock.

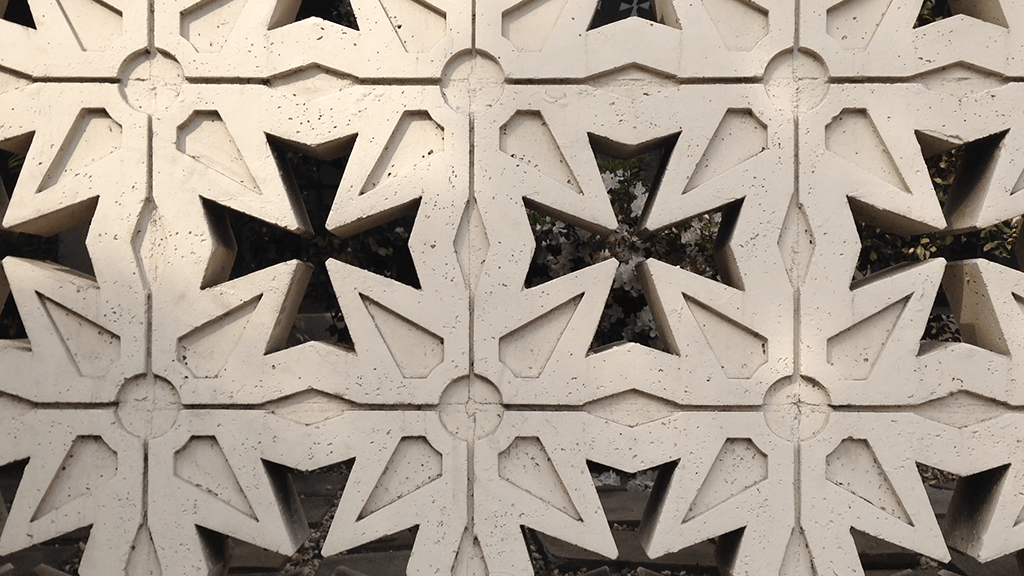

Early in the state’s history, Spanish missionaries covered their buildings in an older version of stucco and thus set the decorative tone for the 20th century building frenzy to come.10 Much of Southern California is covered in stucco. It is serious business here, more than just a way to cover your home or office to hide the cracks created by a shifting foundation or earthquakes. Stucco lends tone and visual texture to the entire metropolis. It’s a part of the city’s urban character and distinguishes Los Angeles from other major American cities. It covers homes and commercial buildings, old and new, in poor and wealthy neighborhoods, regardless of architectural style or heritage. If Los Angeles is a large layered cake, with the exception of raw gray concrete, stucco is the slathered on icing that covers most of it.

There are a variety of techniques for the application of stucco, depending on the form it will be applied to, the desired aesthetic, and the budget. It comes in many styles and the colors are often mixed directly into the cement and sand. Once applied, there is no need to paint over it. Stucco can be indiscriminately sprayed onto just about any surface using a hopper, but hand application and pattern development with a trowel can produce a more artisanal effect. The visual vocabulary of stucco is fairly modest, with most of the ornamental variations split between the texture and thickness of the sand, as well as the troweling technique used in the final application. The most commonly seen applications are Cat Face, Dash, Lace, English, Sand or Float, Worm, Spanish and, at the high end, a smooth Santa Barbara style finish.

More often than not, stucco tends to be an accent to the kind of architectural form it is mated with — or perhaps it’s an affectation. For Spanish style homes there is no aluminum siding, the very thought of it could be considered a kind of heresy. For a Spanish or Mission style home, it’s stucco or arson. I have seen Victorian and Craftsman-style homes, once clad in wood, irreverently sprayed with stucco to make them fit in with newer suburban developments that have come in their wake. Weird permutations of European homes in Los Angeles—such as English Tudor, German or Storybook, French Normandy, and Georgian Revival — get some amount of exterior stucco treatment too. Even Art Deco, Mid-Century Modern and Modern homes, all incorporate stucco as their go-to treatment for exterior walls. Stucco is universal and, as such, invisible.

10 Turenne, Veronique De. “Stucco: The Marble of Suburbia.” Los Angeles Times, 14 April 2005.

[CLICK ON THE RED MARKER TO VIEW VIDEO]

Additional Parking, Palms.

I once read about a young entrepreneur in Los Angeles who would set up clubs and bars at various locations around the city. The trademark of his business was not naming the space at all, he wouldn’t even post a sign above the front door to let anyone identify where the place actually was. When asked about this, he said his basic idea was to think of his venues as secret celebrity bars. He didn’t want the locations to be secret so that celebrities could hang out there without being bothered. The idea was for the person who knew the secret location to have momentary celebrity amongst the friends they invited to hang out there.

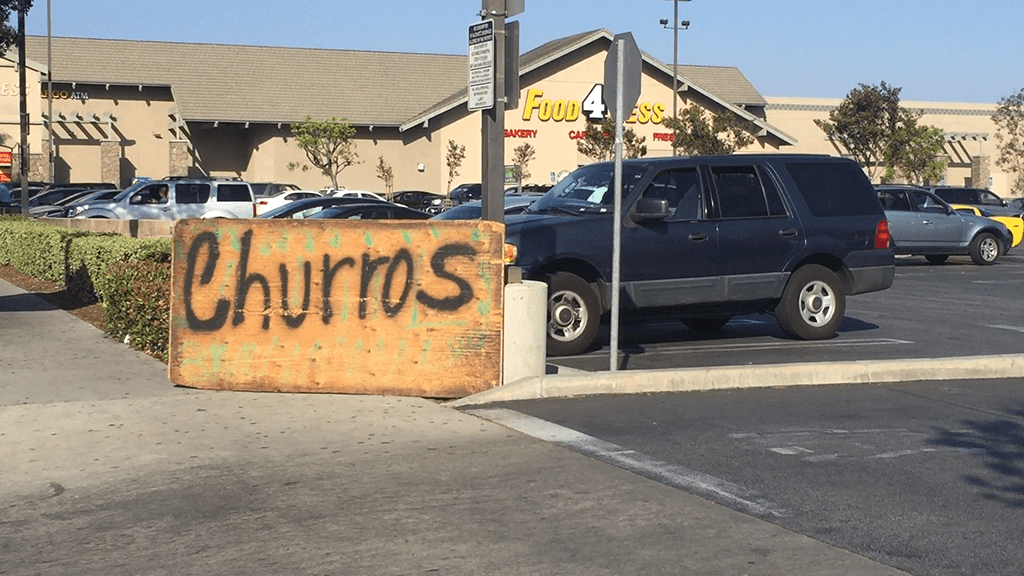

Los Angeles is a large and fibrous place, a city full of back doors and hidden pockets. Jonathan Gold, the Pulitzer Prize-winning food critic, knew this. He spent his life digging around the food scene in this city, writing well about some of the big-name restaurants, but enamored like many of us, with trying to find the rich and rewarding tastes of obscure hole-in-the-wall places. He opened up small worlds of culture and taste for us, revealing cities within the city and places tucked away in plain sight. This kind of effort always involves getting away from what you know and finding a way into the unknown, into what I would call the additional parking, which is never the prime location everyone wants. It’s always somewhere else, somewhere that’s usually a pain in the rear end to get to, a place removed from the center.

Can a city like Los Angeles be thought of in these terms? Is there something more distant, removed, and even secretive about how people live here? Does the city’s vastness inhibit the potential for shared experience amongst its residents? Los Angeles isn’t a huge tourist destination — like Paris, London, or New York — because it’s a place not easily digested by its visitors, a place without an objective identity that you can take a selfie in front of. Living in Los Angeles allows one to remain away from the sticky core, stationed on the periphery and somewhat removed from all its commotion and energy. To reside here is to live with a sense of constant slippage, socially and intellectually. Its centers are orbited by shifting peripheries. There are celebrated places to go and unique things to do, but one can choose to dim all of it out and remain detached and alone. Los Angeles asks existential questions of its occupants, constantly challenging a sense of self in relation to its whole.

The city is spread out and decentralized, it can leave you feeling insignificant and a little lonely. In my first year of living here, another newcomer friend and I would drive all over the city, desperately trying to gather together some sense of where we were and how we were a part of it. After weeks of doing this we finally gave up. We grabbed some beers and drove up into the Hollywood Hills to take in the endless expanse of the city from a vista point. We drank our beers and looked out onto a city that dissolved into itself. It was visually breathtaking, but the real beauty of the moment was the acceptance of our failure. We had resigned ourselves to the notion that we could not obtain any clear idea of where we were. What we didn’t understand at the time was that Los Angeles is not one place, it is many places, perhaps even thousands of different places. Outside of the Hollywood inspired fantasy city that tourists try to assemble — Beverly Hills, Malibu, Hollywood — Los Angeles is a city of Additional Parking, of neighborhoods and communities that are far away from the kind of centralized collective identity of practically any other major city we had experienced before. We had found our place in the city but like everyone else, we were still lost.

Industrial Building, Pacoima.

Greek Life, University of Southern California.

Boots, West Adams.

Jefferson Church, Jefferson Park.

Allsorts, Glendale.

Topiaries, Chatsworth.

Ivy League, Sunset Strip.

Legs, North Hollywood.

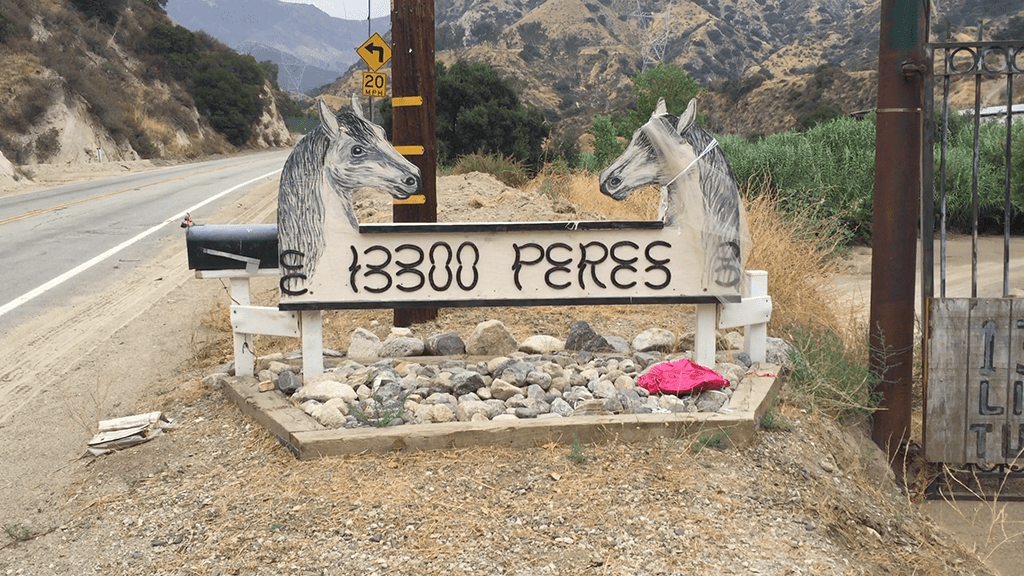

13300 Peres, Lakeview Terrace

Won’s Market, Silverlake.

Vicky’s Star, Hollywood Boulevard.

Hikers, Runyon Canyon.

Do Not Shoot, Chinatown.

PUG, Playa Del Rey.

Various Birdhouse Ranch Homes, San Fernando Valley.

The homes seen here were predominantly constructed in post-war Los Angeles by suburban house developer William Mellenthin. They’re known as the Birdhouse Ranch Houses because they came with a small birdhouse structure built onto the home. They are sprinkled throughout the lower half of the San Fernando Valley, with a large concentration appearing along Magnolia Boulevard. Even though Mellenthin didn’t design the birdhouses, he used them as a kind of signature on many of the modest middle-class homes he built. The birdhouses, or dovecotes, were usually built onto the front of the garage, while others were built right into the siding of certain houses. They seem like one of those funny little quirks that developers came up with as a departure from the usual cookie-cutter homes built at the time. Oddly enough, it’s unclear if any of them are functional as bird residences.

Lowrider, North Hollywood.

Chair, Hollywood.

University Christian Church, Fox Hills.

The Rowena Palms, Los Feliz.

The Queens Arms, Eagle Rock.

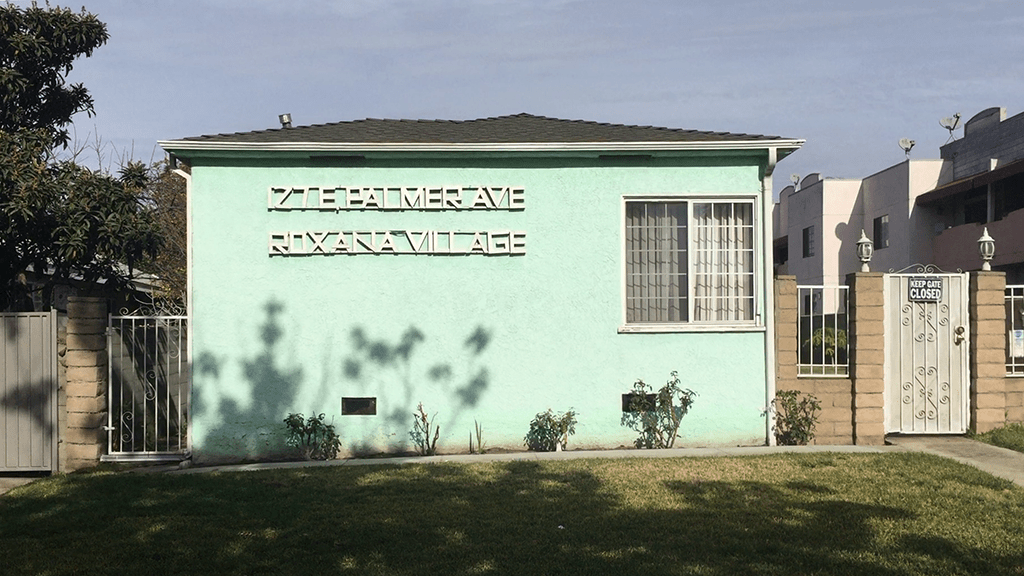

Roxana Village apartments, Glendale.

Fishing, Hermosa Beach Pier.

Old Train Bridge, South Gate.

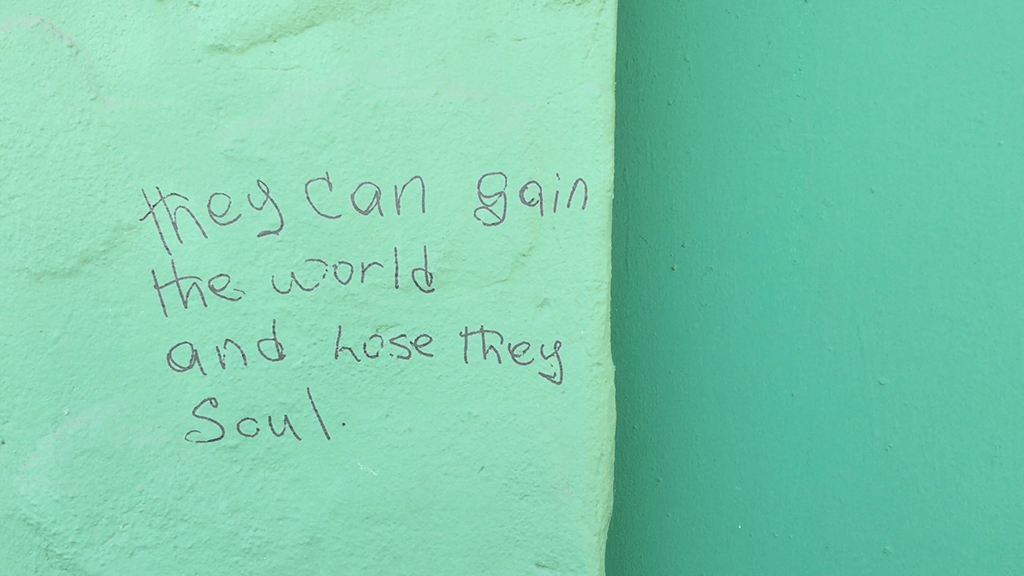

Proverb On Souls, South Los Angeles.

Tags, Highland Park.

Free, Chinatown.

Unspoken Words, Venice.

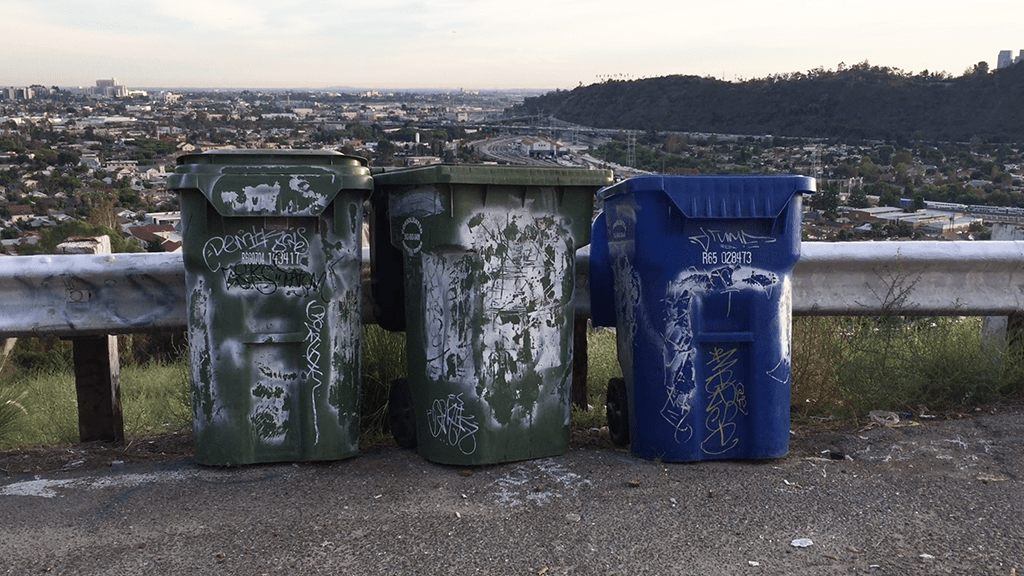

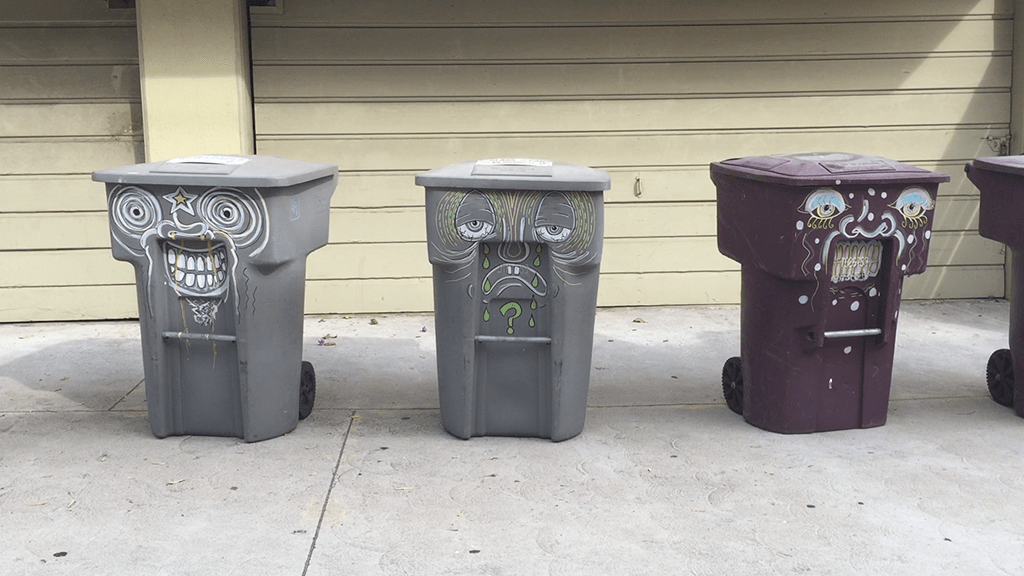

Garbage Cans, Glendale.

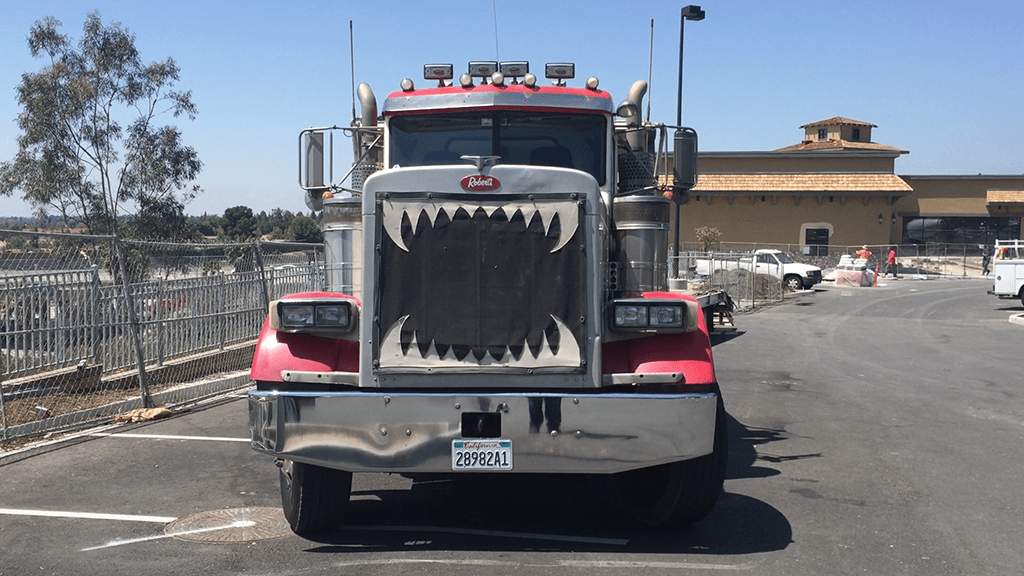

Tough Truck, Rancho Cucamonga.

Borderline, West Hollywood.

Crazy Ex, Pico Union.

Soul Cart, Hollywood.

Two Buildings Meet, Vernon.

City Hall, Maywood.

Another of Los Angeles’ small incorporated cities, Maywood measures in at a mere 1.18 square miles in total size. Although it’s about the size of an average California farm, Maywood is home to roughly 27,000 people, making it the most densely populated city in the state. Unofficially, the number is rumored to be as high as 40,000 residents, taking into account the community of undocumented immigrants living there. Amongst its many problems, Maywood is also a city fraught with police corruption, political wrongdoing, and fiscal mismanagement. Because of these factors, in 2010 the city outsourced most of its municipal services as well as the entire police department, contracting outside companies to handle all public services. Most of the few political figures who are elected to operate the city have little to no experience or any understanding of how local government works. Former Maywood Mayor Ramon Medina, and a number of other city officials, were recently charged with bribery and corruption by Los Angeles County prosecutors.11

Many small cities in the area — such as Bell, Huntington, Vernon, Cudahy, and Huntington Park — have suffered similar kinds of civic catastrophes in the hands of inexperienced or indifferent politicians. These cities run down the 710/110 freeway industrial corridor and are places that are more concerned with business than they are with the quality of life of their citizens. Maywood’s residents are mostly immigrants, mostly Latino, and tend to keep a low profile due to the sketchy nature of the guns for hire police department. It came as no surprise that in the early 2000’s it became one of the state’s first sanctuary cities.

The city started as a real estate development in the 1920s. Maywood was named after May Wood, a woman who worked for the real estate corporation that built the area. It quickly turned into a company town when Chrysler and Ford set up assembly plants there. After the Second World War, the city’s prosperity and economic development slowly dissolved and relocated to other areas, leaving Maywood to be picked over by industrial and political vultures. Business and industry have run roughshod over the city for much of its post-war existence, culminating with the aforementioned implosion of its local political system in the 2010s. Despite all of this, the city’s residents have been able to create a sense of home and community.

Maywood reminds me of another small industrial community in Los Angeles called Frogtown. Squeezed between the 5, the 2 and 110 freeways, along with the Los Angeles River, Frogtown consisted of mostly industrial buildings with a smattering of small homes for the mostly immigrant population that worked there. However, within the last decade Frogtown has been almost completely repurchased and rebranded into a hipster haven. The small bungalows that once housed working families have been demolished and rebuilt into two-story mini lofts that look like they were manufactured by IKEA’s Nordic Noir department. The industrial manufacturing buildings have been converted into tech business buildings or New Age candle and macramé studios. The river, once home to hundreds of homeless people, is slowly being cleaned up and turned into an urban kayaking destination.

Frogtown is close to where I live and the swiftness of this transition has only been outweighed by its severity. Looking back to South Central Los Angeles, places like Maywood could easily be swept up by development and recoded as affordable living for the ballooning intake of hipsters pushing their way out of the ever more expensive central city. The low threshold of resistance put up by a corrupt local governing body makes it easy for what is fast becoming a kind of corporate gentrification of these small communities. What starts with a few artists moving into the neighborhood, quickly evolves into real estate developers with in-house urban planners, figuring out how to reformulate places like Maywood into riverside properties with city views and café lattes.

11 Queally, James, and Ruben Vives. “Ex-Maywood mayor, 10 others charged in bribery, corruption scandal.” Los Angeles Times, 4 Feb. 2021

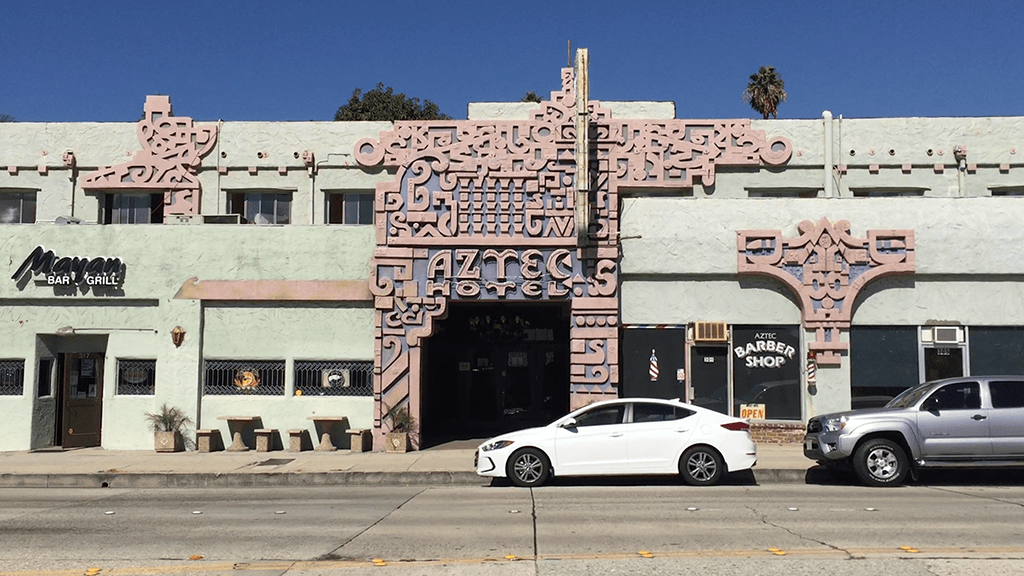

Aztec Hotel, Monrovia.

The Aztec Hotel was built in 1924 and is located along historic Route 66. It was designed by an eccentric English architect named Robert Stacy-Judd, who also built homes, movie stage sets, and was somehow associated with the design of Howard Hughes’ wooden Spruce Goose.12 There are many odd things about this building, the foremost being its name, which would be more in sync with the attempted architectural styling if it was called the Mayan Hotel — but given that all of the external decorative elements are made out of stucco, it’s probably a moot point. Its present-day location reveals how the city has changed over the last century. Route 66 was once the main highway for people traveling west into Los Angeles. It was also used by city dwellers to escape to the mountains — Mount Baldy and Lake Arrowhead — or to the desert, towards Palm Springs. The Aztec Hotel was once a very popular destination, it was either the last stop before you got into town or a watering hole to stop at on your way out. As cars got faster and were able to go further, bigger freeways without traffic lights became more prevalent. The 210 freeway altered the flow of people traveling along the foothills, and places like the Aztec became hidden amongst suburban sprawl, surrounded by strip malls and other local businesses. Since there aren’t a lot of travelers passing through the area anymore, there have been recent attempts to inject different businesses into the building and rethink its function. Maybe future archeologists will find it buried in foliage and ponder why the locals conspired to murder so much cultural heritage in one location.

12 Rasmussen, Cecilia. “Maya Landmark on Route 66 Haunts of Actors, Ghosts.” Los Angeles Times, 25 March 2001.

Besant Lodge, Beachwood Canyon.

Although I’ve never found myself inside the Besant Lodge, I have stood in front of it and admired its ornately carved front doors. The Lodge was originally built as a silent movie theater where Hollywood directors would screen their films and consort with each other. After the silent film era, Orson Welles, Joan Crawford and others participated in theater productions and became part of what was then known as the Beachwood Players.13 Beachwood Canyon, where the lodge is located, was also home to a large Theosophical community that referred to the area as Krotona. They purchased the building in the early 1950s, even though they had mostly vacated the area by then, using it as a performance and lecture space. Aldous Huxley and Gerald Heard were some of the many people who lectured there.

Krotona was the national headquarters of the Theosophical Society in the early 20th century. The basic tenets of their thinking revolved around the equality of the sexes and universal brotherhood, as well as an effort to find a basic truth derived from all religions. A variety of well-known architects were hired to create a multitude of buildings with a mostly Moorish but entirely eclectic set of cultural and religious influences. At the time, this was very attractive to a city-dwelling middle class disaffected with the demands of modern life and also limited by their religious perspectives. Krotona was large and campus-like, spearheaded by the Krotona Inn, which was considered to be the heart of the community.

Beachwood Canyon was a peaceful retreat away from the hustle and bustle of Hollywood and greater Los Angeles, and Krotona was spread out over the small, idyllic canyon.14 In 1923, the Hollywood sign was hoisted on Mount Lee, just above Beachwood Canyon, as a real estate gimmick to attract buyers to the area. It worked, the sign cemented itself into Los Angeles history. Coincidentally, in the following year, Krotona relocated to Ojai and became Krotona 2, where it still resides to this day. Owned by the Theosophists, the Besant Lodge and all of the original Krotona buildings have been repurposed into apartments, private homes, and spaces that serve the present community — a community no longer united by any sort of philosophical or religious purpose. Despite the hordes of camera-toting tourists hunting for the Hollywood sign and a highlight on their Instagram feed, this area still harbors the ghosts of its utopian past in relative secrecy.

These type of communities have thrived in the greater Los Angeles area, perhaps it’s the lack of urban definition that has allowed small niche societies to flourish and survive — as well as self-implode under their own systems of thought. There are powerful global groups like the Church of Scientology and the Unification Church, but there’s also a bigger history of smaller and less corporate collectives like the Source Family, the Church of Synanon, the Symbionese Liberation Army, and the Manson clan, to name just a few. Many of these groups have created a physical presence through architecture, building redevelopment, and real estate acquisition. Scientology has repurposed an enormous quantity of buildings and real estate in Los Angeles including the Château Élysée — just down the street from Krotona 1, the campus of KCET, and the former Cedars of Lebanon Hospital. Except for Scientology, most of these groups are fading or have completely disappeared off the radar, much like the Theosophists who called Krotona 1 home. Collectively, they have all etched their marks into Los Angeles, leaving not just their physical traces but an indelible philosophical impression that adheres to the basic premise that anything is possible.

13 “About.” Besant Lodge of the Theosophical Society, http://www.besantlodge.com/about.html

14 Meares, Hadley. “The Creation of Beachwood Canyon’s Theosophist Dreamland.” Curbed Los Angeles, 22 May 2014.

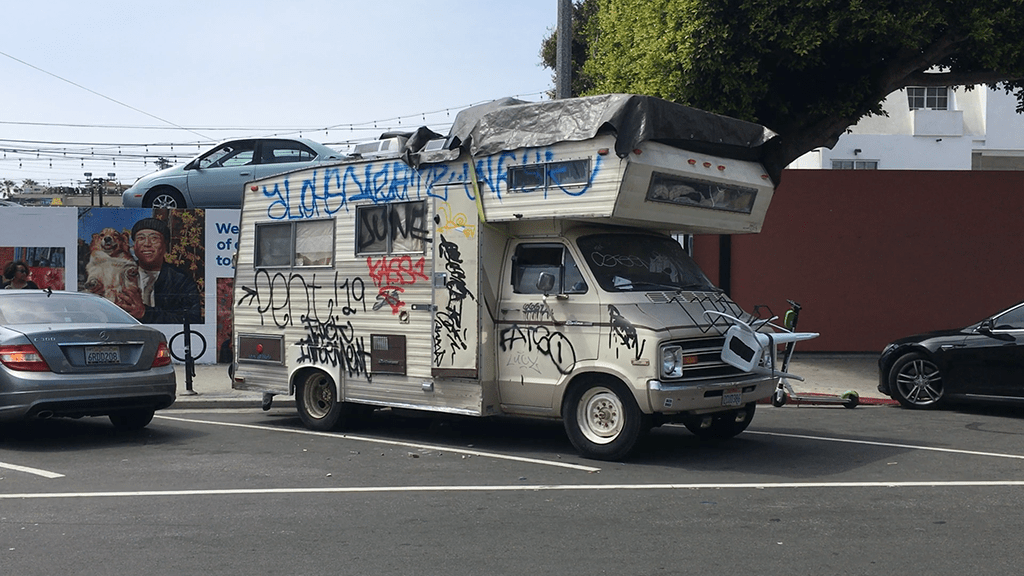

Abandoned RV, Van Nuys.

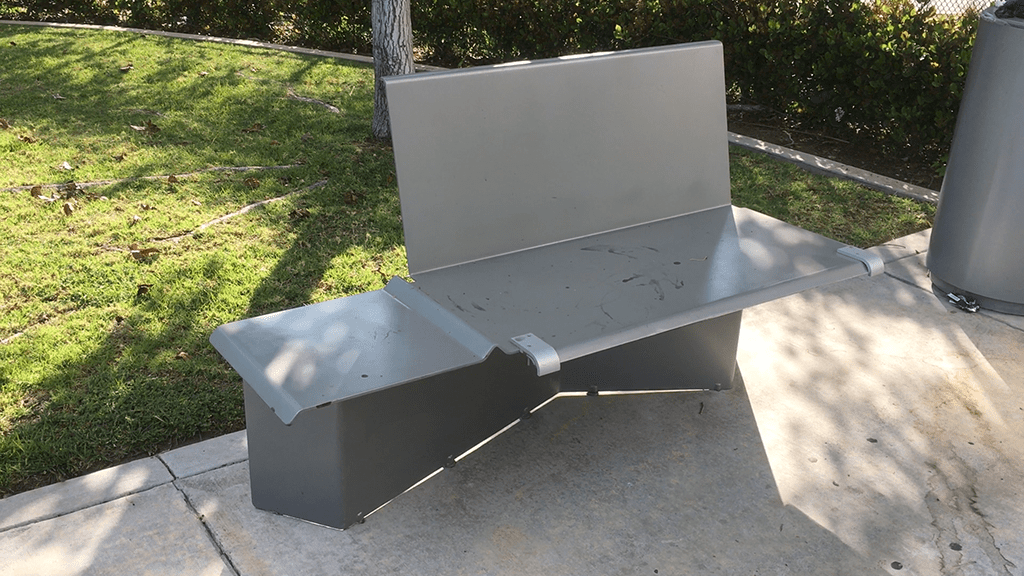

Homeless Proof Public Bench, Downtown Los Angeles.

Homeless Proof Public Bench, Culver City.

Homeless Proof Public Bench, Century City.

Public Bench, University Park.

[CLICK ON THE RED MARKER TO VIEW VIDEO]

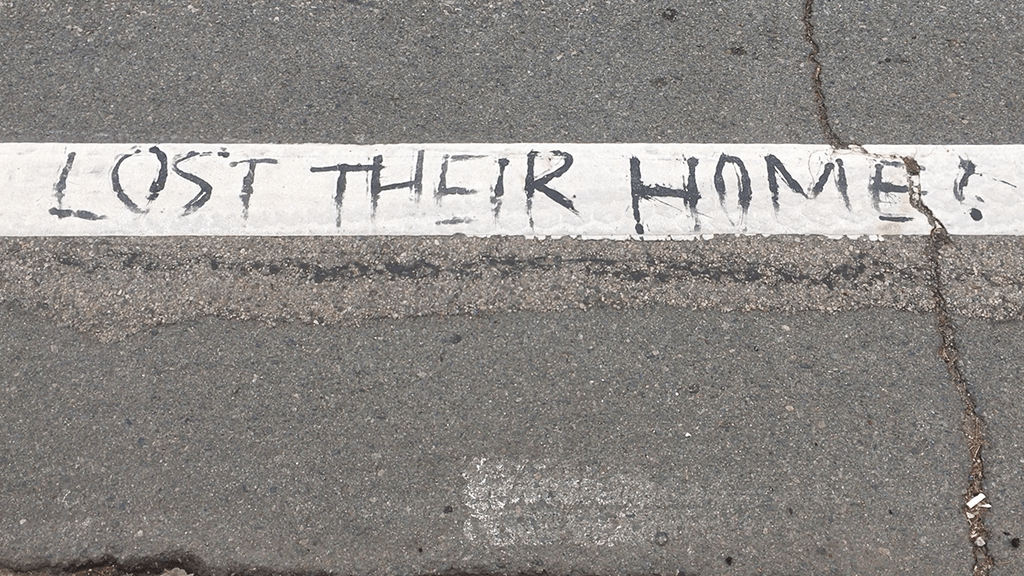

Eviction Help, Exposition Park.

Motel, South Los Angeles.

Accidental Abstraction, Valley Glen.

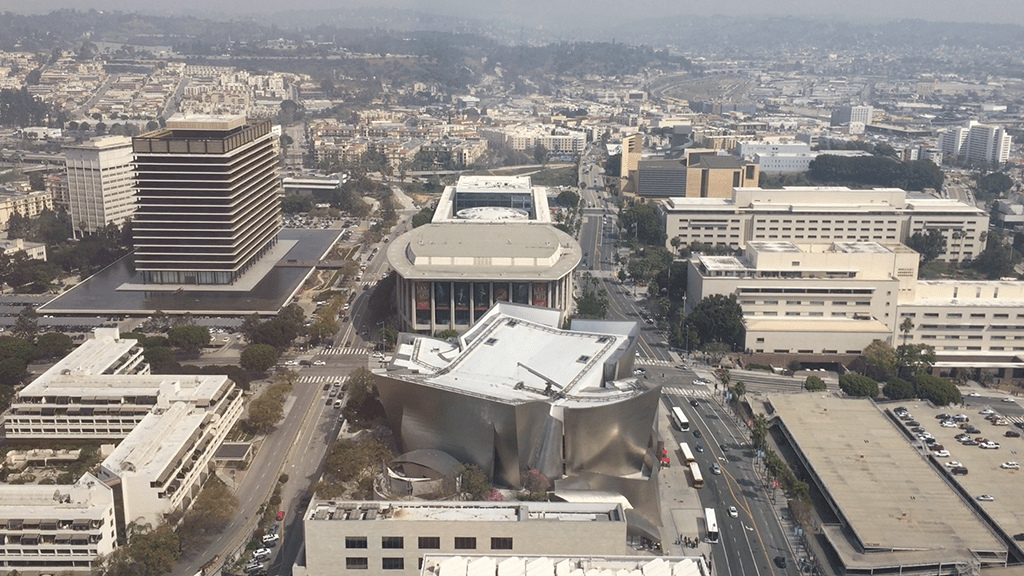

Above Grand Avenue, Downtown Los Angeles.

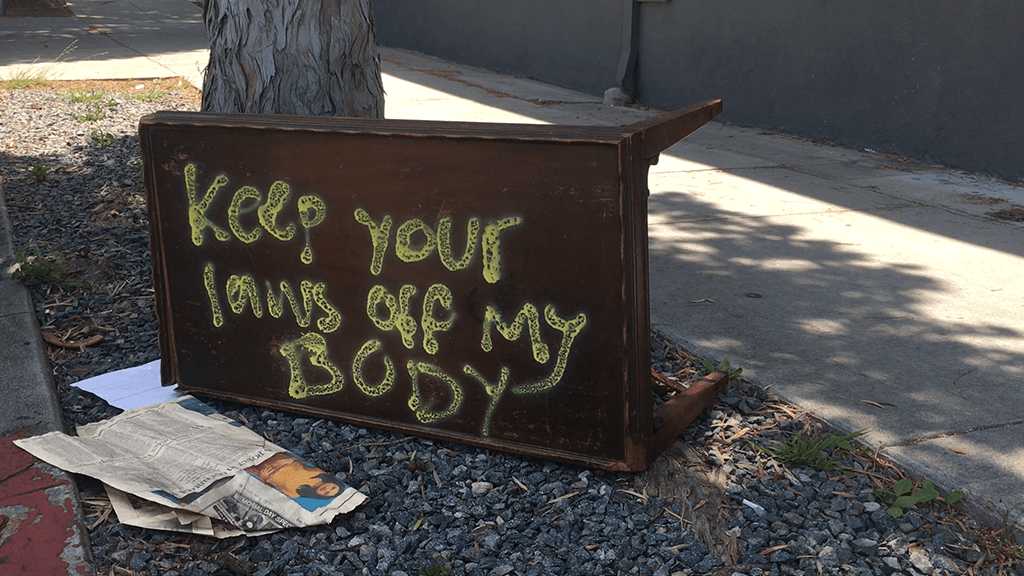

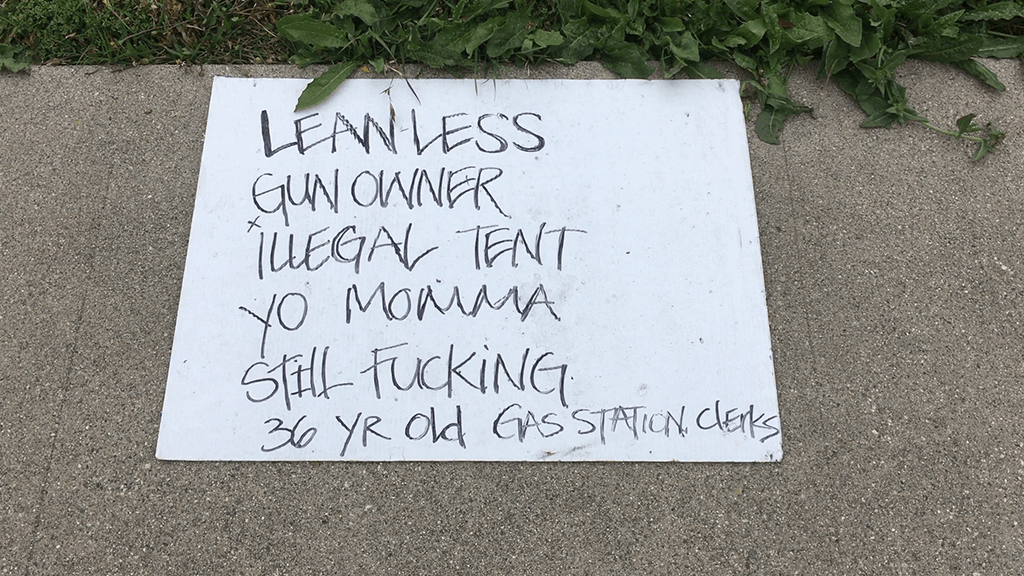

Zen and the Art of Protesting, Circle Park, Downtown Los Angeles.

Apartment Building, Van Nuys.

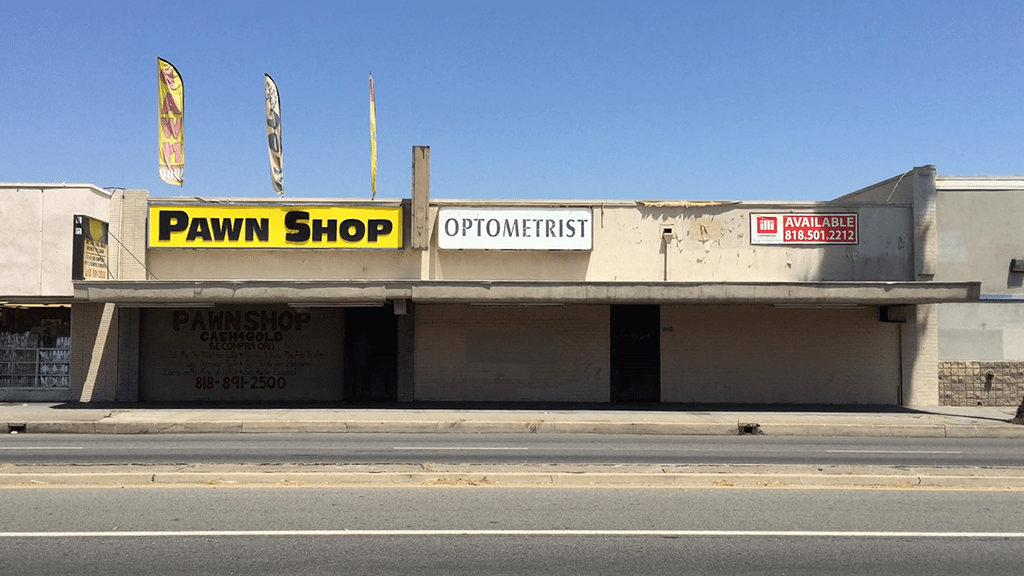

Pawn Shop, Van Nuys.

Window Fix, North Hills.

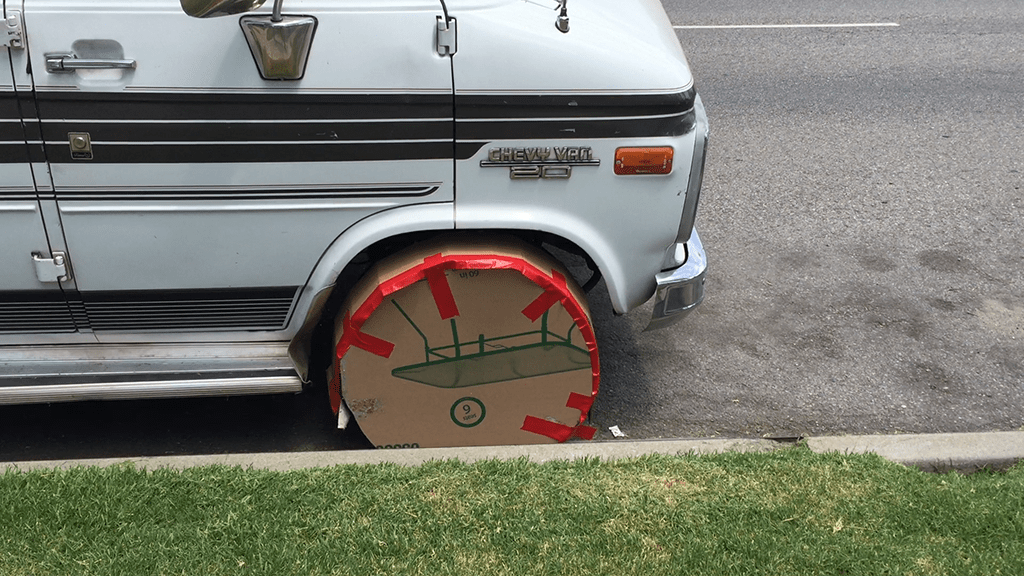

Cardboard Boot, North Hills East.

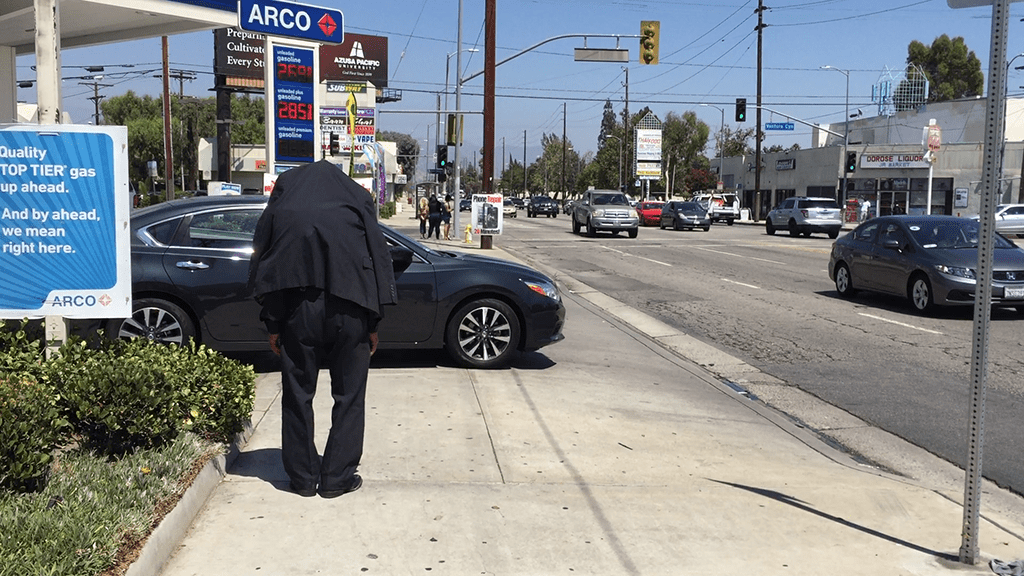

Man in a Suit, Panorama City.

Dead Dog, Vermont Vista.

Someone Loves You, Venice.

Fancy Fence, Glassell Park.

Box Man, Sagamore Park.

Tagged Billboard, Reseda.

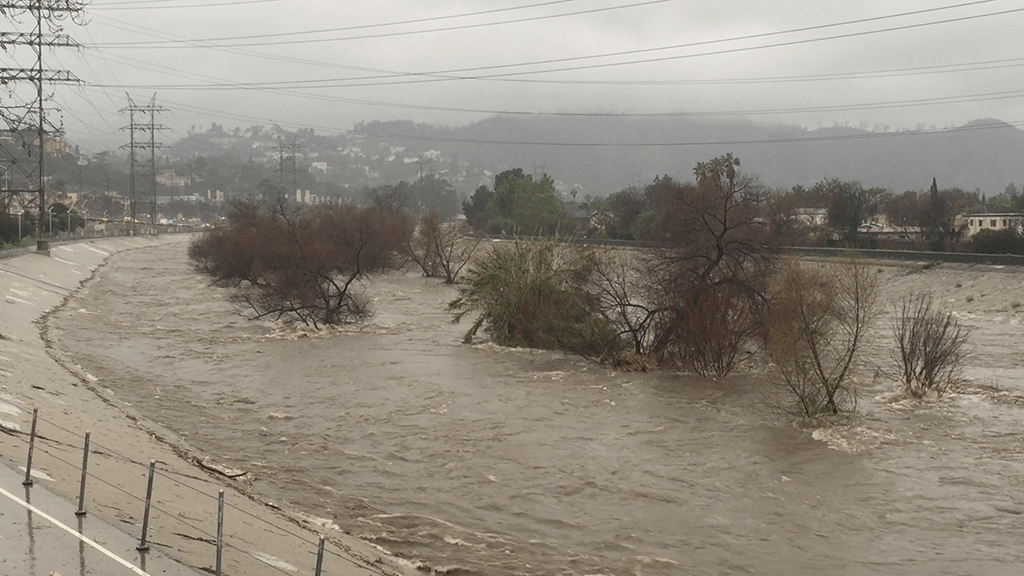

Los Angeles River, Atwater Village.

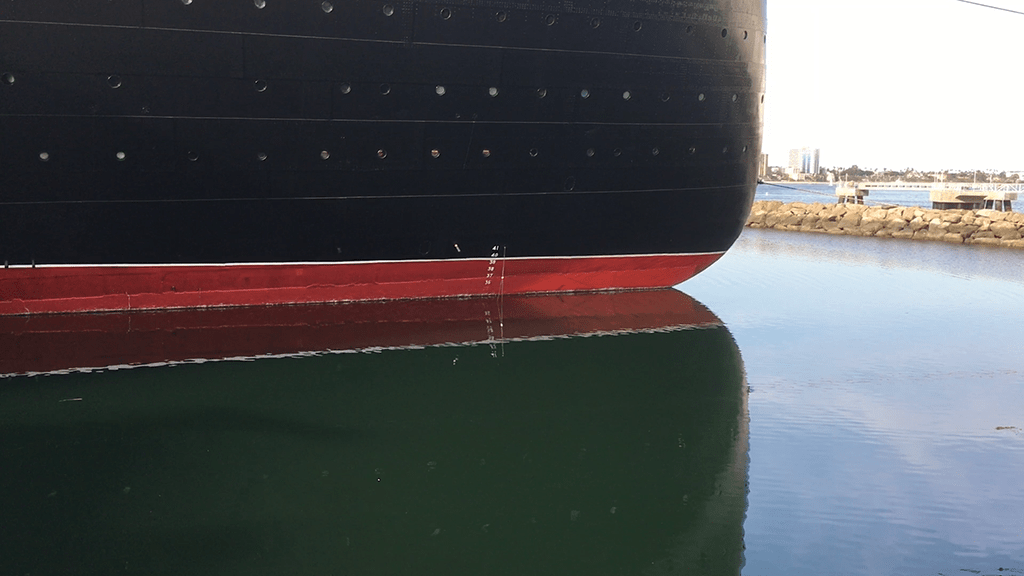

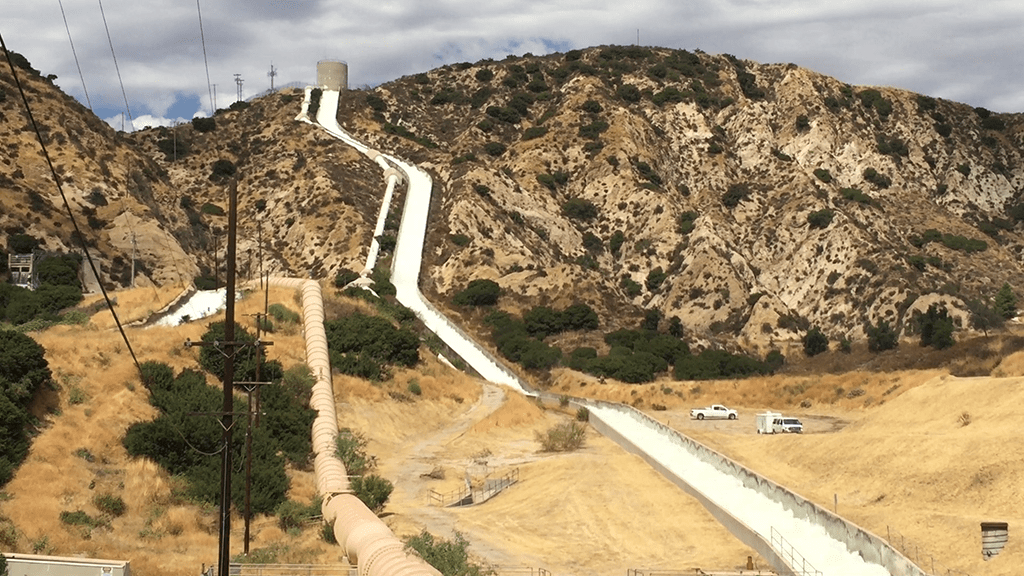

Many visitors and newcomers to Los Angeles wonder why most of the city’s waterways and its main river are encased in concrete. This image was shot across the river from Atwater Village, and it shows a terrifyingly huge amount of water barreling its way through the city during one of Southern California’s infrequent rainstorms. Atwater Village is a small neighborhood with a history of flooding during heavy seasonal rainfall. A stretch of the river that runs alongside Burbank, Glendale, Atwater Village, and Downtown is so prone to flooding that records show 17 floods happened in the area between 1815 and 1938.15 Flooding damaged private and public properties, destroyed bridges, and sometimes it led to the death of people living in those areas. In the 1938 flood, 1500 homes were destroyed, bridges collapsed, and a total of 96 people lost their lives.

Los Angeles is surrounded by mountains that can receive up to 40 inches of rain per year, compared to the city’s average of only 15 inches. The mountains used to funnel rainwater down to the city into a mostly dry riverbed that would swell up and breach its banks. To remedy this, the Army Corps of Engineers built the concrete version of the Los Angeles River between 1936 and 1959. Despite the charges of aesthetic treason, the concrete banks of the river do their job and flooding has become an issue of the past. However, a recent study by the Army Corps of Engineers says the area could still experience a massive 100-year rainfall. This, combined with the runoff from a now vastly denser urban environment, could create a water flow that the concrete river might not be able to hold. FEMA has therefore suggested that neighborhood residents obtain flood insurance and prepare for the worst.

When it isn’t functioning as a flood control channel, the Los Angeles River is mostly dry. There is a small and constant flow of water during the summer months, but most river users are unaware that this is mainly generated by three water treatment plants in Burbank, Glendale, and Los Angeles respectively.16 It is said that this water is safer than the urban runoff from city gutters that it combines with. There is also a sizable homeless population who use the riverbed and its sparse foliage for security and privacy. Combined with all of the waste and trash that magically ends up in the river, the water quality is clearly considered unsafe. Heal the Bay periodically tests the river water for fecal indicator bacteria. In a 2015 study, it was found that bacteria levels “exceeded federal standards 100% of the time at two sites in Elysian Valley and 50% of the time in Sepulveda Basin.”17 This contaminated water is literally flushed out into the ocean during any significant rain event in the area. Long Beach receives most of this flow, but beaches from Orange County to Malibu will put out bacteria advisories and even shut down during and after rain events.

Freshwater is central to life in Los Angeles. We drink it, fill our pools with it, water our golf courses with it, while forgetting what a precious resource it really is. Most of the water used in Southern California comes from elsewhere. There is local groundwater present, but the bulk of what we use is diverted our way via aqueducts from the Sierra Nevada mountains and the Colorado River. Water is like cheap champagne in Los Angeles — life here wouldn’t be possible without it. We over consume and import way more water than we need, storing next to none of it, letting the excess flush most of our waste out into the Pacific. The inebriation it provides helps us believe we’re not living in a concrete desert and that the urban collision between man and nature in Los Angeles isn’t just another disaster movie in the making.

15 Salazar, David A. “The LA River and Corps: A brief History.” Los Angeles Public Affairs Website, 3 Oct. 2013, http://www.spl.usace.army.mil/

16 Guerin, Emily. “LA Explained: The Los Angeles River.” LAist, 22 June, 2018.

17 “FAQ: Is it Safe to Recreate in the L.A. River?” Heal the Bay, 25 Aug. 2016, http://www.healthebay.org/faq/

Custom Stucco, Montecito Heights.

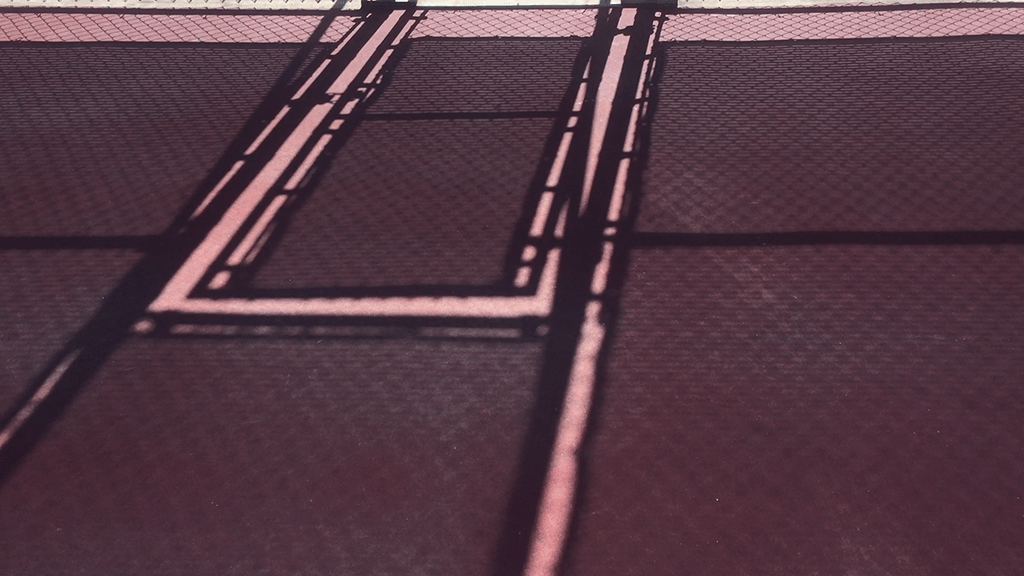

Tennis Courts, Sierra Madre.

Understudy, Hollywood.

Budweiser Typography, Van Nuys.

Kruse Family Typography, Glassell Park.

Ghost Bicycles, Cypress Park.

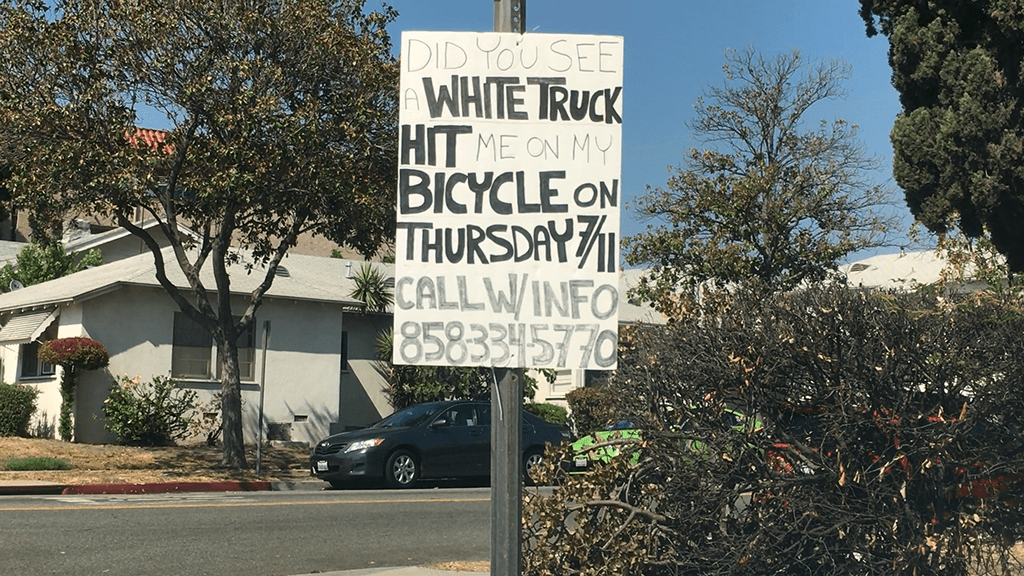

It is a sad thing to see so many of these ghost bicycles memorializing dead riders around Los Angeles. It’s actually an infuriating reminder of the political incompetence of the city’s leadership and their inability to properly use funding allocated to making the streets safer. It shouldn’t be surprising, but Los Angeles, according to http://www.bicycling.com, is the worst bicycling city in the United States. Los Angeles is a participating city in Vision Zero, an initiative to make the streets of urban areas safer for everyone and eliminate traffic-related fatalities by engineering and designing safer roadways for cars, bicyclists, and pedestrians. This is an international effort that started in Sweden and has expanded to different countries since the late ’90s. In most major cities where Vision Zero has been implemented, there have been significant declines in accidents and fatalities related to automobiles. But not in Los Angeles, in fact, quite the opposite — fatalities have risen despite the city’s efforts to create bike lanes, improve pedestrian visibility, and monitor areas of high incidents.

According to a Los Angeles Times article “rather than decline, fatal car crashes have risen 32% since 2015, the year Vision Zero began. In that time, more people have died in traffic collisions — 932 — than were shot to death in the city.”18 These are alarming numbers — gun fatalities are another story. Even former Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa wasn’t spared, when out riding his bike he got into an accident with a taxi on Venice Boulevard and broke his elbow. There are countless stories of cyclists being seriously injured or killed by cars — sometimes even being left in the streets to die in hit-and-run incidents. A rider killed in April of 2018 was struck by two different drivers, both fled the scene. Another rider was struck and killed by a distracted Los Angeles Sheriff while patrolling Mulholland Drive.19 In the five years of filming Additional Parking, I’ve walked, used public transit and mostly biked my way around the city. I was honked at by drivers, faux-rammed by them, spat on, knocked over once, and survived two minor accidents. Los Angeles is not a city for bike riders. It’s a city full of bad, distracted, and often aggressive drivers who want to paint your bike white.

18 Nelson, Laura J. “More people are dying on L.A.’s streets despite a push to eliminate traffic fatalities.” Los Angeles Times, 25 April 2019.

19 Flax, Peter. “Los Angeles is the worst bike city in America.” Bicycling, 10 Oct. 2018, http://www.bicycling.com

Under the Sixth Street Viaduct, Downtown

Hidden under the Sixth Street Viaduct there is a not-so-secret passageway for getting down into the Los Angeles River. This access point is probably used by Hollywood crews to get down there to shoot all those classic L.A. River car chase/race scenes. Anyone who finds their way through the tunnel and into the river experiences a very unique thrill, which may or may not be caused by the almost toxic stench the water gives off. Sadly, the bridge was demolished in 2016, a victim of bad concrete from 1932, when it was constructed, as well as concerns of seismic instability related to its deterioration. During the demolition, the city actually gave out chunks of the concrete rubble to hundreds of people who had lined up to collect an odd piece of Los Angeles history. The viaduct has recently been replaced with a newly designed bridge by Los Angeles architect Michael Maltzan. Although the new bridge looks like it was flown in from a more architecturally enlightened country, the ruthlessly brutalist charm of the old bridge made its mark on the city’s identity.

Car Wash, Glendale.

Trash Collector, Van Nuys.

Laundry Day, Pacoima.

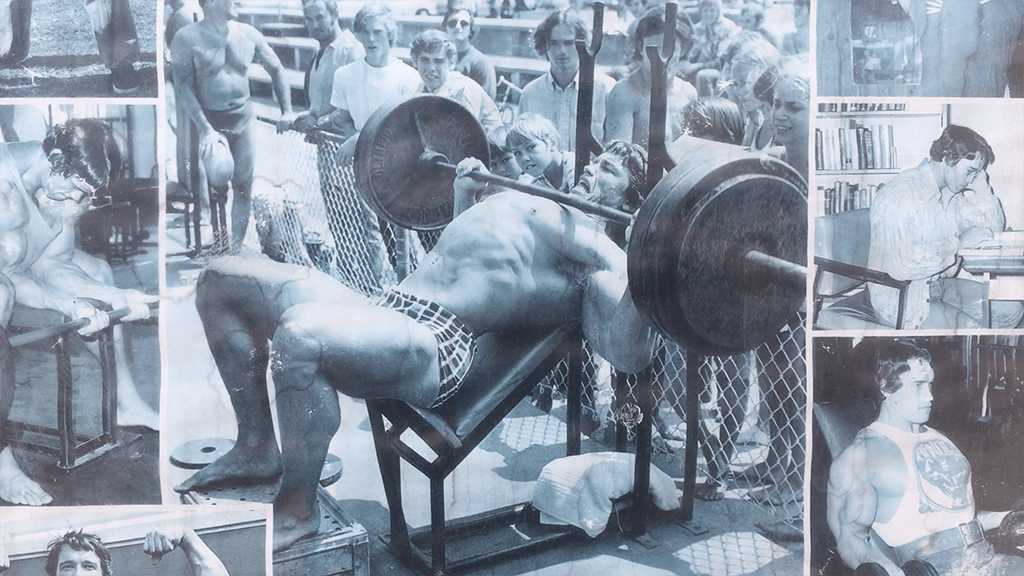

Hans and Frans, Atwater Village.

Heart of Palm, Chatsworth.

Detour, Northridge.

Greyhound Bus Station, San Fernando.

Nano’s Discount Store, Panorama City.

Hindu Temple, Chatsworth.

Skirts for Sale, MacArthur Park.

Southern California Christ’s Church, Westlake.

Camouflage, Winnetka.

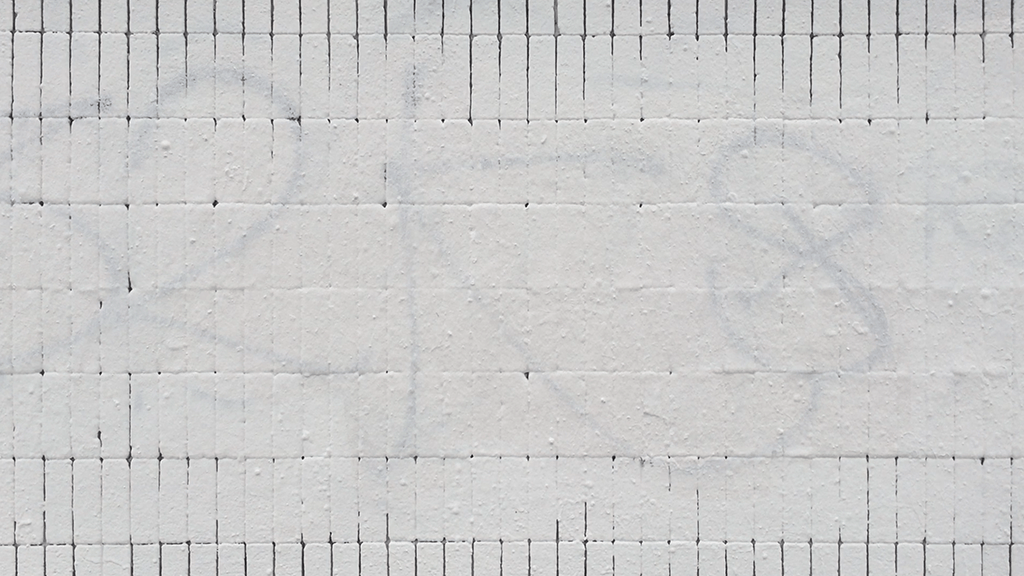

This was a Painting, Glendale.

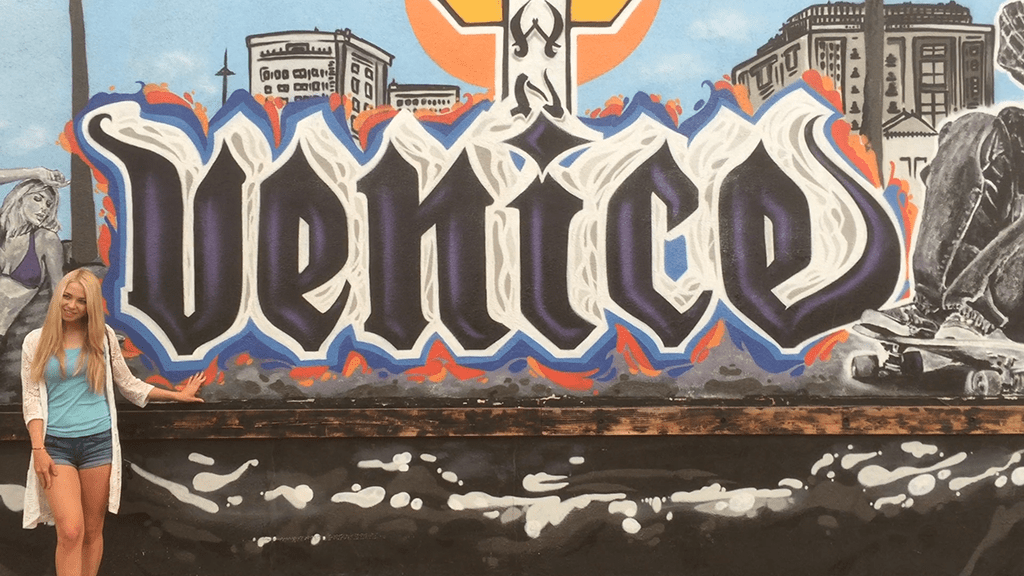

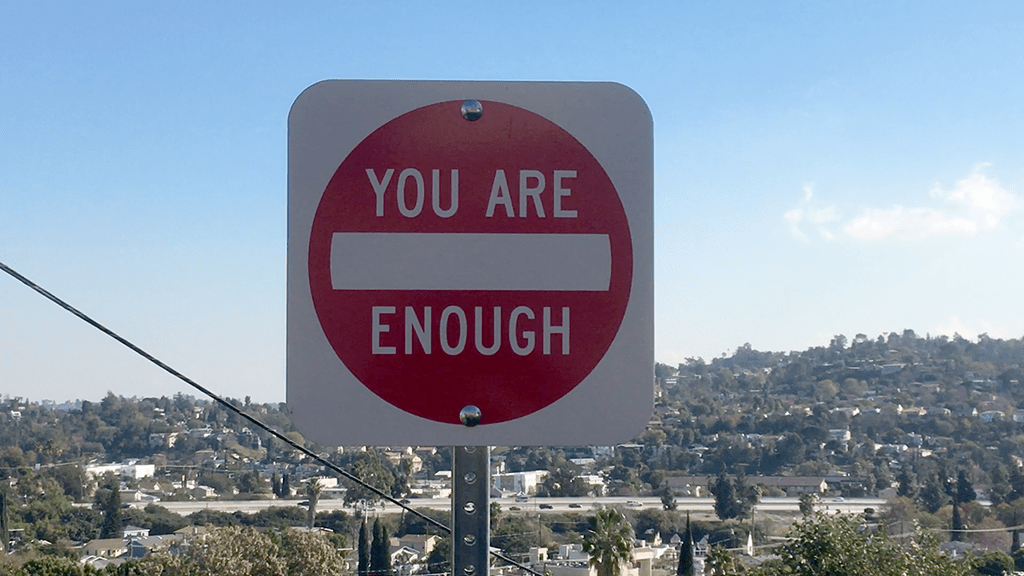

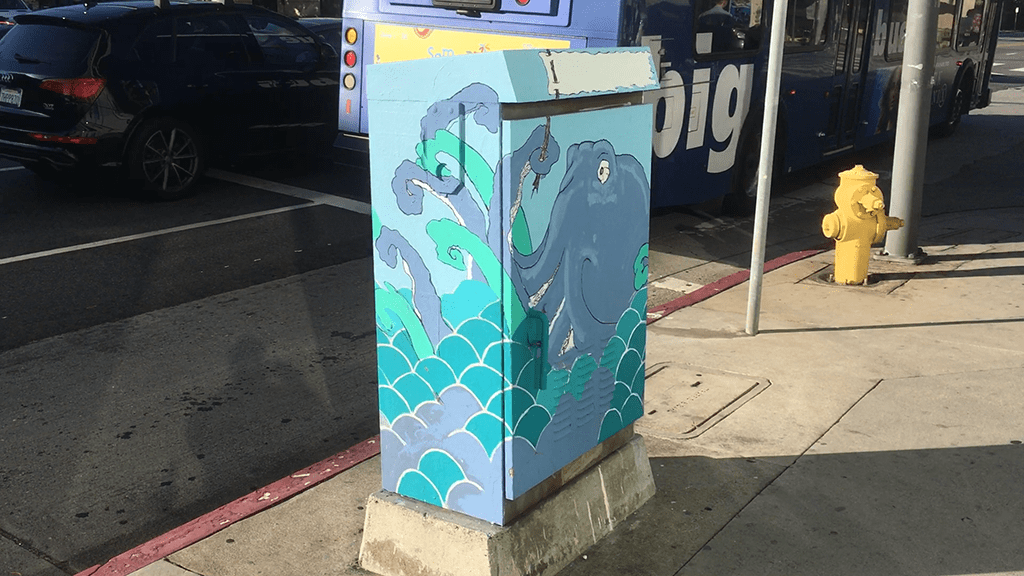

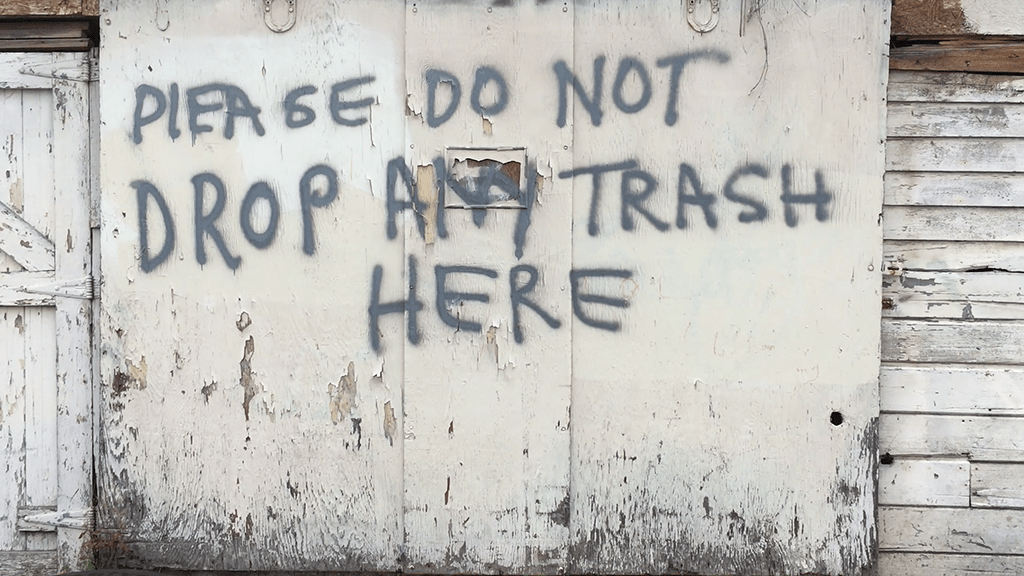

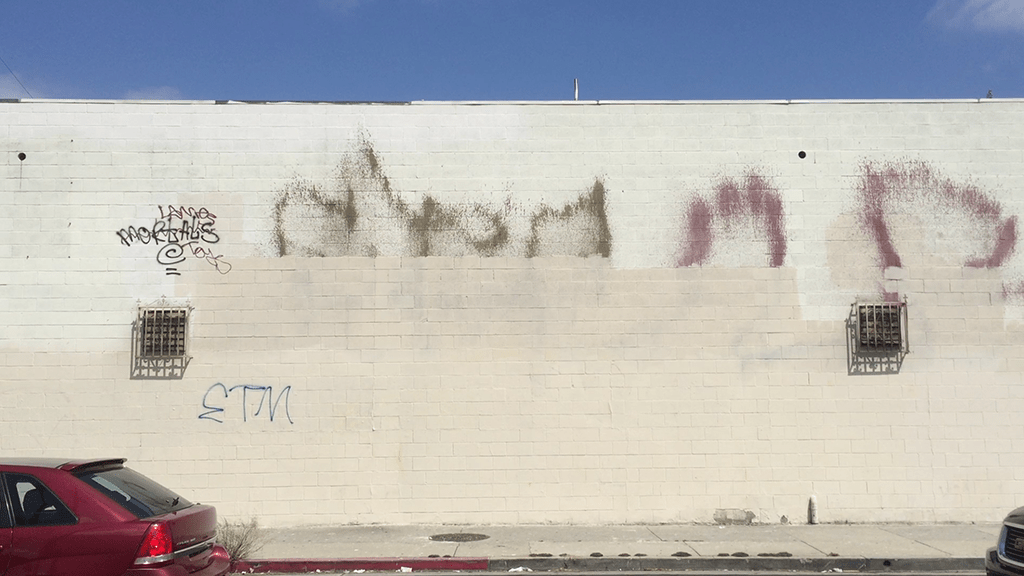

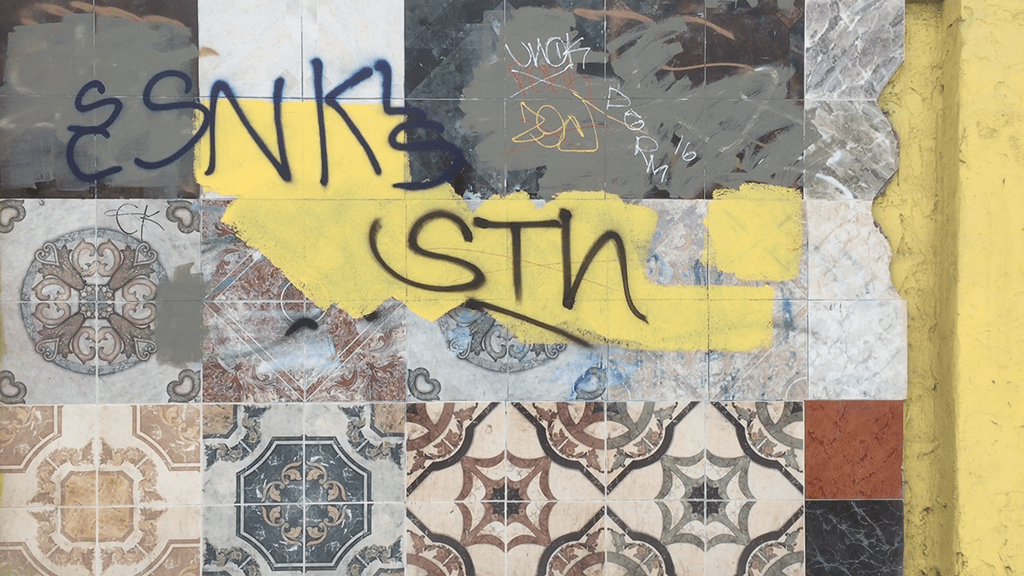

The Los Angeles metropolitan area has hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions of building walls with inscriptions and paintings on them. In some neighborhoods, store owners will depict the products they sell on the shop’s exterior walls. Some buildings have official or unofficial murals, just about everywhere in the city has some form of graffiti — from religious paintings to decorative abstractions, to painted wings for selfies, things written in foreign languages, and all sorts of gang tags that change depending on where you are. Even graffiti that has been painted over create amazing abstractions that function as strange post-linguistic thought bubbles. I find these wall paintings to be one of the most interesting and unique by-products of the city’s multiethnic identities. It is one of the ways that the citizens of Los Angeles indirectly communicate and intellectually intermingle with each other.

Upon seeing this nondescript wall in an industrial corridor of Glendale, Magritte’s The Treachery of Images immediately came to mind. This was a painting but it is no longer a painting. What is it then? I have looked carefully at the image and I can see the faint outline of some writing, perhaps graffiti, but I can’t really be sure. Was there a mural that was painted over with graffiti and then painted over again to obscure the graffiti, and then painted on once again to give us “this was a painting” as a final summary of everything? Hard to know. Even if this is true, aren’t we left with a painting nonetheless, one that perhaps John Baldessari would have been proud of? I recently checked, the wall has now been returned to the blue ground it began as. Google street views sometimes have a feature that shows a history of the images their cameras take in a particular spot. There were no such recordings made at this particular location. I suppose it doesn’t matter in the end. What we’re left with carries an ambiguous eloquence, a jumble of symbolic projections that reflect back upon one another.

I think about the phrase “this was a painting” as a kind of metaphor for what Los Angeles looked like in terms of landscape, before and after Europeans showed up, and its development ever since. There are reminders of what the land might have looked like in the imposing mountain terrain that surrounds the city. The Angeles National Forest hasn’t suffered a lot of tampering and it somewhat serves as a time machine for those who venture up there. When the Spanish missionaries arrived, they built churches and small townships as they developed the agriculture of the basin land. According to the US Census Bureau, in 1850 the population of Los Angeles was only 1610 people — that same year, California was annexed into the United States. Its population has been ballooning ever since, growing exponentially every decade. The growth chart of the region shoots upwards consistently, with small bursts here and there, steadily documenting the relentless influx of immigrants. The city has been in a constant process of expansion and development, building and rebuilding itself over and over again. These historical layers of the city can be hard to find as a result of the neglect shown by the city planning office.

Los Angeles does not dwell on its past, any place in this city can face the bulldozers and bricklayers if it means getting more people to pay out for more mortgages and rent. Currently, the vast majority of the city is going through another growth spurt, with an unprecedented amount of horrific high-density dwellings shooting up all over the place. Downtown as well, with a rejuvenated desire for compact vertical living, has seen a boom of residential high-rise buildings flying up with a fair amount of regularity. Up until the 1990s, the city continued to expand outwards towards the high desert. This is still ongoing, but there are limits to long car commutes, because of poor mass transit infrastructure the city must now build upwards and on top of itself, adding yet another fresh layer to its own urban history. I find myself wondering what the city will look like for the incoming generations of wanderers who end up here. Will it be, as most people expect, the apocalyptic acid rain-soaked shithole depicted in Blade Runner? Or will it just be a dumping ground for cultural and philosophical bric-a-brac? A matter of fact warning, like Margritte’s, to all who misunderstand what they’re looking at.

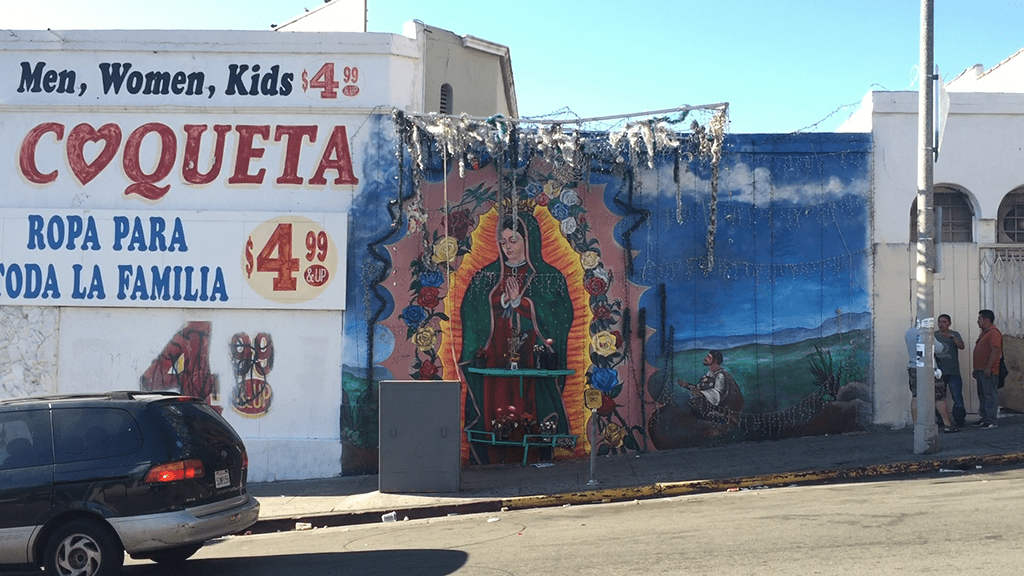

The Virgin of Guadalupe, South Westlake.

The Alpine Market, West Carson.

Abstraction, Ocean Park.

The Eighties, Venice.

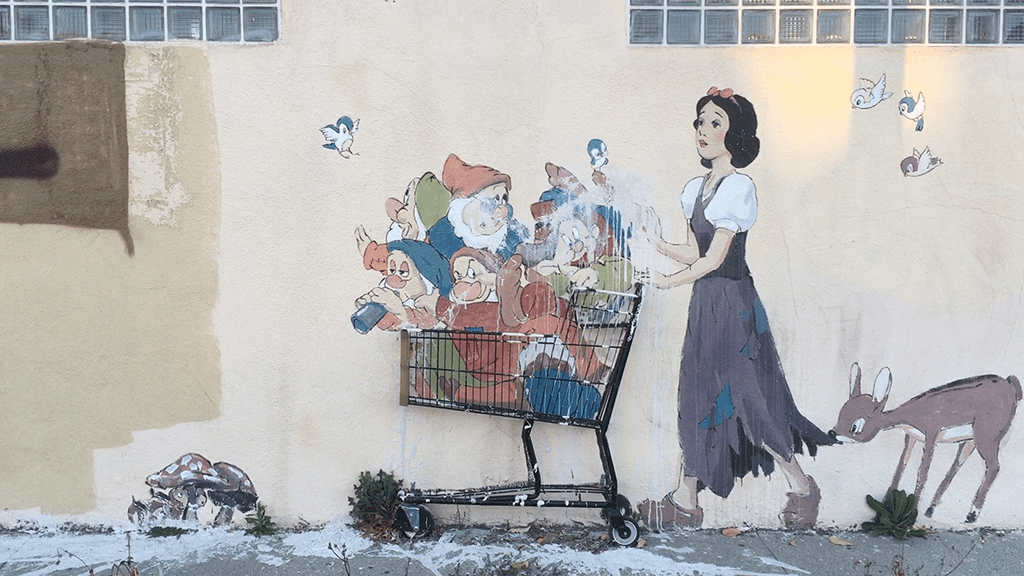

Snow White, Culver City.

Nipsey Hussle Memorial, Fox Hills.

Market Murals, Playa Del Rey.

Inside Out(side), Valley Glen.

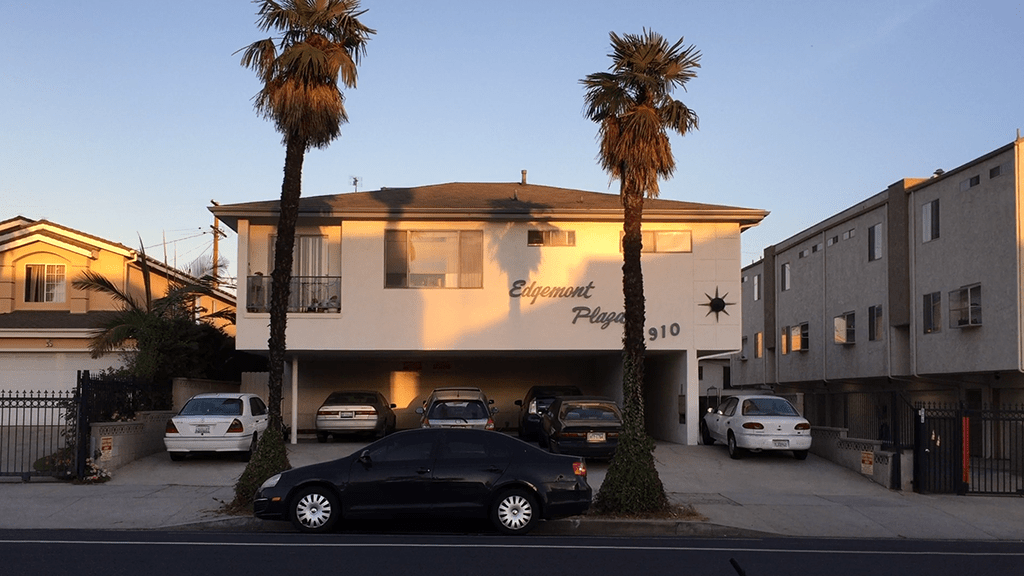

Edgemont Plaza, East Hollywood.

The Pink Flamingo, Studio City.

The Alamar, Hollywood.

Cheri D, Santa Monica.

The four images above represent the most typical kind of apartments in Los Angeles: Dingbats. They tend to inspire indifference from most people but in recent years many have been torn down and replaced with higher occupancy buildings. Indifference has shifted to a kind of nostalgia, they actually seem quaint now. However, they are being replaced with what I refer to as The New Dingbats, shown below. These buildings have underground parking and a commercial ground level topped with three to four levels of residential apartments. Tacked-on exteriors tend to match the dress codes of potential occupants, ranging from business casual, to confused serial killer, to Dieter visits America. All seems to amount to the same thing.

[CLICK ON THE RED MARKER TO VIEW VIDEO]

Dingbat Manor, West Los Angeles.

Casa Dingbat, Palms.

The Dinglebat, Beverly Hills.

Chez Dingbat, Mid-Wilshire.

The Present, Van Nuys.

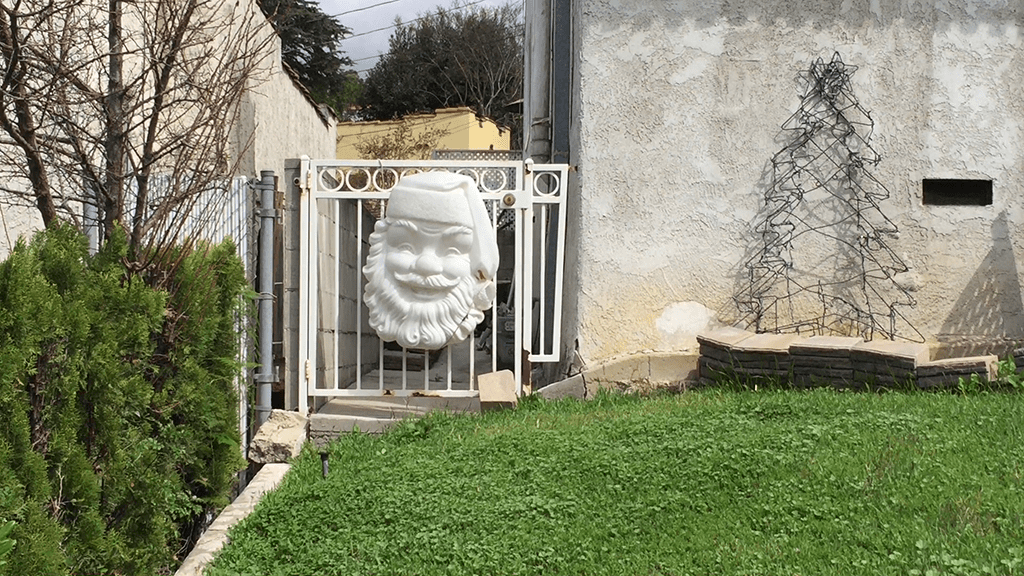

Yard Art, Encino.

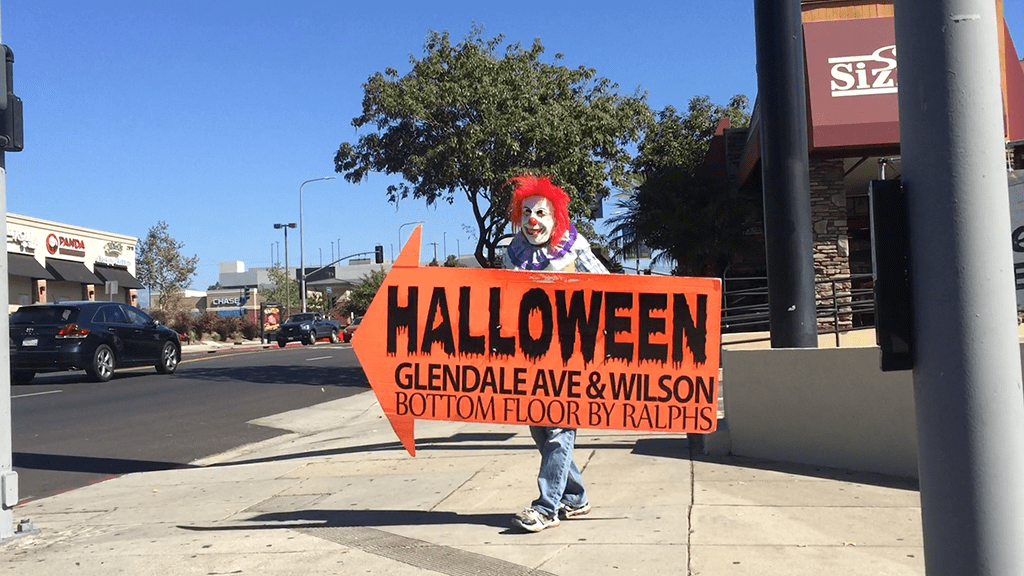

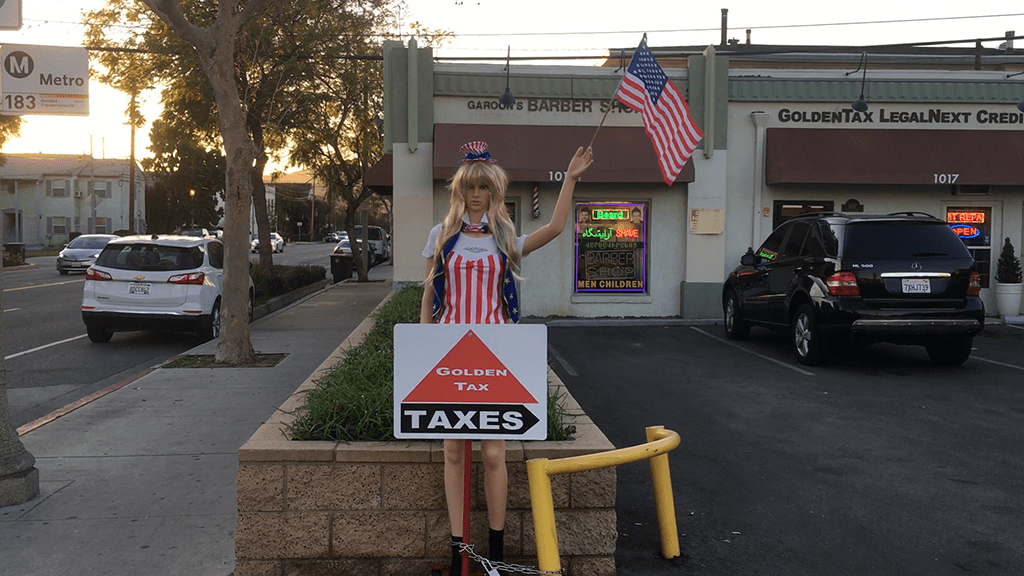

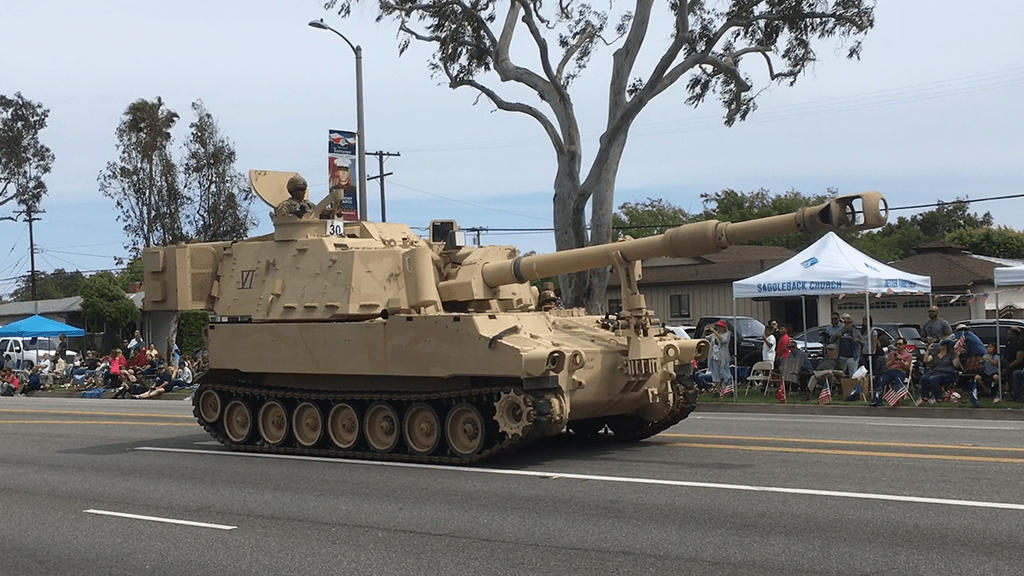

In other areas of Southern California, like Irvine or throughout the beach communities, there are very specific rules about how houses are built and how they’re painted, landscaped, and ornamented. Although there are rules in Los Angeles, they are far less strict and seemingly unenforced. Despite the efforts of a few pockets of local development and many outlying gated communities — areas attempting to emulate right-wing territorial fascism of states like Texas and Florida — Los Angeles is, and somehow remains, the great unplanned community. Homeowners do as they please in regards to the exterior decoration and presentation of their properties. Front yard art, curated and installed by the homeowner, can be found just about everywhere in the United States, but especially in Los Angeles. Perhaps it’s because of the city’s proximity to Disneyland and Hollywood, that many of these front yard installations seem to operate with a certain benchmark of production values. They are often well made, going out of their way to get the attention of the neighbors and entertain passersby. They can communicate a symbolic order unencumbered by the pretensions of the art world. Many of them seek to percolate the American psyche, developing personal themes directly addressed to a larger audience. Most reflect the kitschy dramas of Disney tableaus and often seek to recreate some cultural event or a favored perspective. One of my neighbors, much to the dismay of the rest of the neighborhood, has recreated battle tableaus from various American wars. His front yard has boasted a recreation of the iconic Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima image, using slightly smaller than life-size figures, constructed with home-mixed concrete and clad in era-appropriate uniforms and helmets.

Additionally, there are seasonal front yard shows that make use of lights, inflatable sculptures, carved pumpkins, a variety of religious motifs, and a horrifying number of plastic ornaments eventually destined for the local landfill. Depending on where you live, this kind of annual activity can work itself into a frenzy. Certain neighborhoods are known for this and attract families from neighboring communities. Many of these particular installations are temporary by design because of their seasonal nature, which makes them less open to ambiguous interpretation. Once a year, another one of my neighbors positions hundreds of commercially produced Santas in their front yard, in rows assigned by height. The arrangement seems to suggest a bizarre school class portrait. The figures have all been damaged by rain, sunshine, and pollution, which gives them a slightly sad and creepy look, one that unwittingly nods to the work of Mike Kelley and Paul McCarthy. Made by artists without institutions or intellectual affiliation, these works are a kind of manifestation of the suburban subconscious. With no written curatorial or artistic statement, no body of past work to draw up, viewers are left to imagine what they will.

Abstraction, Winnetka.

Abstraction, Sylmar.

Industrial Building, San Fernando.

Industrial Building, San Fernando.

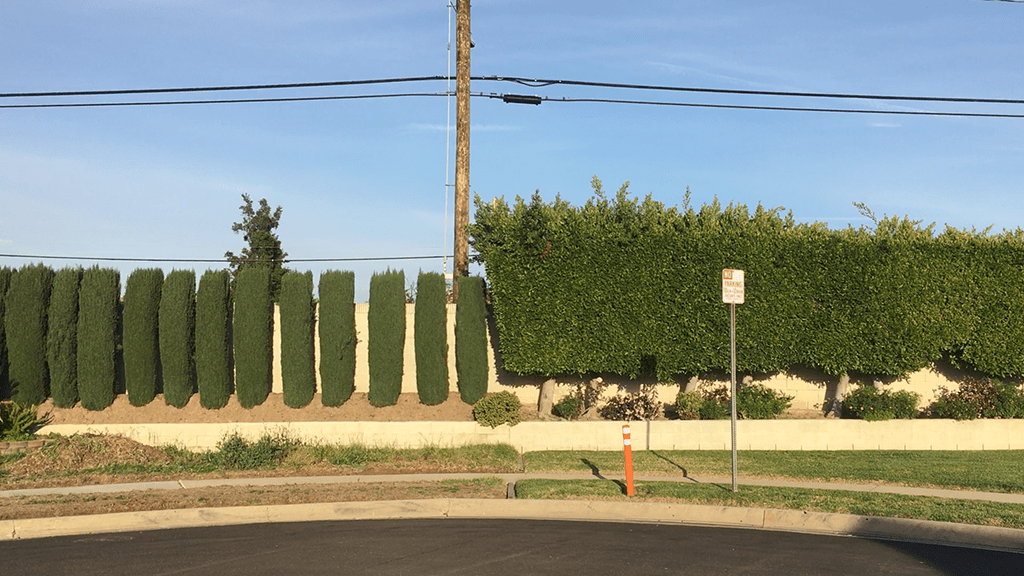

Fence, Beverly Hills.

Fence, Holmby Hills.

Fence, Highland Park.

In Southern California, putting up a fence around a property — particularly in affluent communities like Bel Air and Beverly Hills — explicitly delineates one’s position in the social hierarchy almost as much as the kind of car one has. A cursory drive down the western edges of Sunset Boulevard reveals gigantic fortress-like hedges 20 to 40 feet tall, effectively sealing off the inhabitants from the rest of the citizenry. These fences are often made from Boxwoods, Cherry Laurels, or densely planted Italian Cypress trees, which have tightly packed leaves and branches that require lots of water. As a bonus, they’re graffiti resistant — the LAPD website recommends choosing prickly varieties as an additional deterrent.20 These barriers are a prerequisite for creating compounds and fortresses that not only hide but protect the wealthy owners from outsiders, who are usually seen either as intruders or as possible threats.

A depressing trickle-down of this bunker mentality can now practically be found in all of the city’s neighborhoods. It makes sense that the pretensions of up-and-coming petite bourgeois areas like Westwood, Century City, West Hollywood, and Beverly Grove would adopt this kind of allusion to wealth and status, even spreading below Sunset Blvd and taking root in other working-class and low income areas as well. Highland Park, Mid-City, and even parts of South Los Angeles have smaller smatterings of these hedgedoms popping up all over the place. Its origins probably stem from overly ambitious real estate agents and house flippers catering to a young affluent demographic willing to slum it for the right price.

20 “Get Informed.” Los Angeles Police Department, http://www.lapdonline.org/get_informed/content_basic_view/23481, 2021

Garages, Jefferson Park.

Garbage Niche, Glassell Park.

Burnt Cart, Los Feliz.

Soul Development, Atwater Village.

Butterfly Weed, Venice.

Urban Camper Van, Filipinotown.

Coyote Path, Silverlake.

Free Dirt, Woodland Hills.

Got Rats?, Tarzana.

Techy y su grupo Aroma, Reseda.

Illegal Shooting, West Hills.

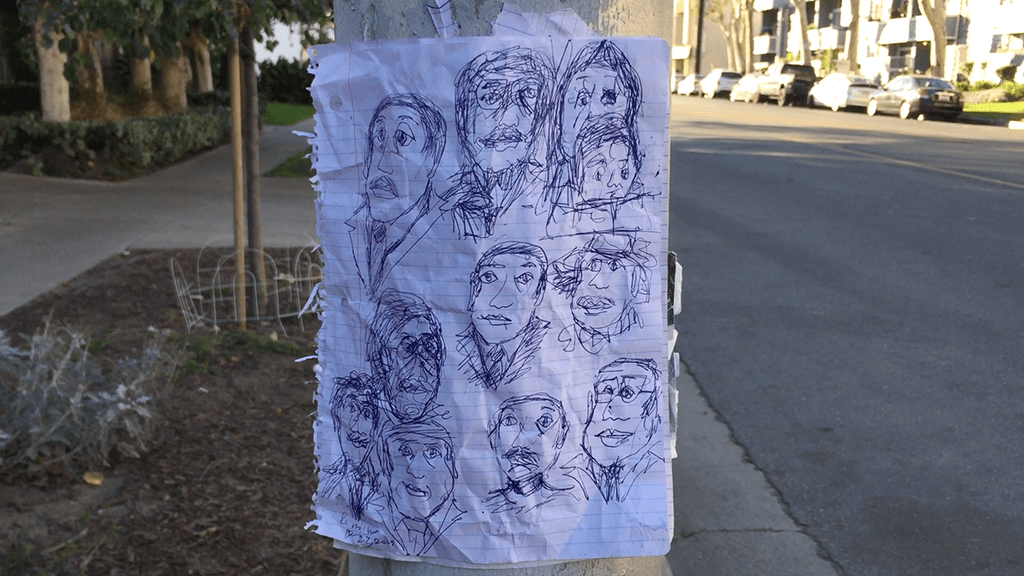

Facial Studies, Valley Village.

Retaining Wall, Montecito Heights.

Decorative Cinder Blocks, Glassell Park.

Turquoise Tiles, Lincoln Heights.

Brick & Lattice Fence, Winnetka.

Plastic Lattice Fencing, Panorama City.

Circular Ironwork, Central Alameda.