On October 31, 1918, the Viennese artist Egon Schiele succumbed to the flu pandemic at the age of 28. The collection of drawings and paintings that he left behind reveals the work of a precocious artist through a remarkably formative period. His prolific—some might say frenetic—output consists of many self-portraits of an ambivalently erotic nature. When we peruse Schiele’s catalogue we are alternately attracted and repulsed—drawn in by the immensity of his talent and then repelled by the skeletal frames, hollowed ventral cavities, and sickly straggles of hair that his nudes present to their viewers.

Consider Self Portrait with Red Eye (Figure 1) and Self-Portrait Masturbating (Figure 2), which dramatize the artist in various stages of partial undress. Schiele renders himself in sparing grey-scale, confronting the viewer with the electric red of his eye contact, or with the flaccidity of his penis. His forehead and ears, well-proportioned in reality, are swollen to cartoonish sizes. What are we to make of an artist intent on equal parts seducing and antagonizing his audience?

Self-portrait with Red Eye, 1910

Gouache and pencil with white heightening

44.9 x 30.7 cm

Self-portrait Masturbating, 1910

Gouache, watercolor, and black crayon

44.8 x 31 cm

In light of his early death, we might be tempted to view Schiele’s self-portraiture as a sort of visual solipsism: a means to display the immensity of a talent that could neither be contained nor redirected into more sophisticated visual allegorization. However, I believe that his self-portraits stand on their own merit, combining into a powerful set of statements the paradox of self-interpretation. Schiele instructs us about the modern urge to self-represent, an invaluable lesson in an era when so many of us have a camera trained at our own faces and at our own bodies, searching for a key to the transcendent in the physical and mundane.

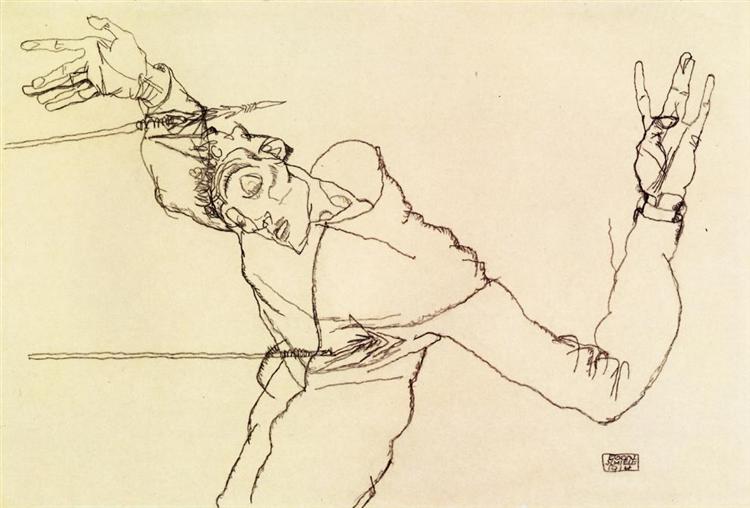

Indeed, much of the self-portraiture that exists from 1910-1912, when the artist was in his early twenties, strikes the viewer as remarkably modern. In Grimacing Man (Figure 3), the figure is rendered with his left arm outstretched, almost as if he is taking a selfie. Similarly, in Self-Portrait with Arm Twisted Above Head (Figure 4), the contorted figure holds his left hand off-frame, as though he might be wielding a front-facing camera. His expression betrays the awareness of a gaze—the consciousness of a viewership beyond the canvas, a community of followers that might recognize themselves in these images.

Grimacing Man (Self Portrait), 1910

Gouache, watercolor, and charcoal

44 x 27.8 cm

Self-portrait with Arm Twisted Above Head, 1910

Watercolor and charcoal

44 x 31.5 cm

Long before technology and media enfranchised the less technically-gifted among us, Schiele unearthed the secret to which most successful modern influencers lay claim: glamour breeds envy, and there is nothing more glamorous than unabashedly reveling in the strangeness of one’s own body. By representing himself repeatedly, in deliberately candid poses, Schiele anticipates today’s moody, febrile self-obsession.

And yet as modern as Schiele’s figures strike us, critics have consistently commented on the historical and religious imagery that he suffused into his landscapes and portraits. Consider Self-Portrait with Peacock Waistcoat (Figure 5) and Self-Portrait with Splayed Fingers (Figure 6), in which the white heightening behind the body glows like a halo or sacred light, an emanation that marks the figure out as holy in the manner of a medieval saint. In the Waistcoat image, Schiele represents himself with a halo around his own head, foreshadowing the religious allegory that he would incorporate, and of the martyred identity that he would assume.

Self-Portrait with Peacock Waistcoat 1911

Gouache, watercolor, and black crayon mounted on cardboard

51.5 x 34.5 cm

Self-portrait with Splayed Fingers, 1911

Gouache, watercolor, and black crayon

52.5 x 28 cm

Like Van Gogh and Gauguin before him, Schiele played with the trope of martyrdom in his self-portraiture, indicating that he viewed himself as an unjustly persecuted visionary, in the image of Christ, who suffered for his status. Consider his facial expressions—the grimace in which his face is often fixed—alongside the physical contortions of his hands—the exaggerated protrusion of his knuckles and phalanges (Figures 6, 7, 8). The reliance on allegory and on the sparing media and techniques that focus on the face and hands recalls pre-Renaissance painting. A master of visual language, Schiele deliberately instrumentalized the vocabulary of the imitatio Christi by adopting the grimace as a sign of martyrdom, and the exaggeration of the hands as both a vehicle and a receptacle for stigmata.

Self-Portrait with Eyelid Pulled Down, 1910

Chalk, watercolor, gouache

44.3 x 30.5 cm

Self-Portrait with Lowered Head, 1912

Oil on wood

42.2 x 33.7 cm

Indeed, Schiele’s short life was marked by trials and pitfalls that must have reinforced his sense of divinely-sanctioned victimhood. Elements of his biography read as a microcosm for the spiritual crossroads at which the Austro-Hungarian Empire, at the dawn of the twentieth century, found itself. As a youth, Schiele violently rejected the classical methods that he was forced to study at art school, fiercely denounced the instructor who insisted on the strictly structured, conformist elements of figure drawing, and, perhaps most importantly, was briefly imprisoned in 1911 when his nude sketches were seized and condemned as corrupting to local youth.

The titles of the works he completed in prison indicate that Schiele saw it as his sacred, inalienable mission to create art (For My Art and For My Loved Ones I Will Gladly Endure Until the End! and Hindering the Artist is a Crime, It is Murdering Life in the Bud!). How do we reconcile the grandiosity of his self-proclaimed mission with the repulsion of the figures and the vulgarity of the nakedness with which they confront us?

Later in the twentieth century, Georges Bataille would examine the line between the sacred and the abject. He considered the thirteenth-century Italian holy woman Angela da Foligno, whose spells of mystic ecstasy moved her to imagine herself licking the wounds of lepers. According to Bataille, self-disgust is a mechanism that has the potential to move us closer to the sublime. Abjection—the breakdown of meaning through degradation—is a means of testing and confirming the love of God. Similarly, in Schiele’s portraiture, we are audience to the exaltation of malady, neurosis, sickliness, and sexual obsession as saintly states of being.

In Figure 9, Self Portrait as Saint Sebastian, Schiele treats us to an explicitly allegorical drawing that dramatizes a legendary martyrdom. His body as Sebastian, rendered in black pencil with an emphasis on the shape of the hands and melancholic, suffering expression on the face, is pierced by two arrows mid-flight. Schiele’s version of Saint Sebastian borrows heavily from Gabriele D’Annunzio’s and Thomas Mann’s vision of the saint as an emblem for the transgressive and countercultural potential of a Catholic icon. Theirs is a focus not on the intercessory powers of the saint, but on his poise and acceptance of his fate amidst unjust torment leveled by a cruel and merciless crowd.

Self-Portrait as Saint Sebastian, 1914

Pencil

32.3 x 48.3 cm

When we synthesize the medieval with the modern, the divine with the abject, we arrive at the crux of Schiele’s obsession with self-representation, and with our enduring fascination with his art: self-representation is a way of moving beyond the profane, of using self-portraiture in order to put our own bodies and faces in dialogue with the sacred. Consider the forms of abjection that social media reduces us to—broadcasting self-consciously curated images that have been carefully filtered, cherry-picked, edited, re-sized. In a ploy for absolute control over the creation of the self, we channel the obsessive, self-conscious attempts at agency that Schiele’s portraits dramatize.

What can Schiele’s self-portraiture reveal to us about individuals as they grapple to articulate an identity? About our need to resolve the dueling impulses of casting ourselves as the protagonists in our stories and having bodies that are ugly, misproportioned receptacles of fever, excrement, and sexual desire? Perhaps Schiele teaches us that self-representation might serve as a vehicle to move us beyond our isolated, fragmented, uncertainly autonomous selves, towards the divine. For Schiele, self-portraiture transcends the mere narcissistic desire for self-love and puts the viewer in touch with—if not God, then—something beyond the visible, something that connects us with versions of ourselves that transcend the ways we merely appear to be.

Cristina Politano is a writer from New Jersey. Her essays can be found at Return.Life and on cristinapolitano.substack.com.