Writer’s guides occupy a precipitous vantage. By some, they’re assumed to be the how-to manuals, the instruction booklets for a product that doesn’t exist yet, a product that comes without a flatpack box, without allen-keys or bolts, that the DIY-builder has to assemble in the dark. By others, they’re thought of as self-help books, ready and willing to ease the reader through the trauma that is being-a-writer, through all the stages of literary grief, through the bardos of artistic torment, before reaching that promised land of acceptance: from oneself, if not from a publisher. Expectations are high. If they aren’t printouts full of cheat-codes, they’d better read more or less the same as the Tibetan Book of The Dead.

Many a good writer’s guide, then, has made many a good doorstop, or desk-side paperweight. When Wisława Szymborska published the wordily titled, Poczta literacka, czyli jak zozstrí (lub nie zoztrí) pisarzem, in the year 2000, she had been a Nobel Laureate poet for four years. But her writings collected in the book had been composed over a long period of production, and can’t be said to be a result of her status as a recipient of the coveted prize. Szymborska served on the editorial board of Literary Life, a Kraków-based journal from 1953 to 1981. In 1968, alongside novelist and critic Włodzimierz Maciąg, she began a column for aspiring writers: the Literary Mailbox, at a time when she had already published at least seven works, including Poezje wybrane, her selected poems of 1967. Her responses, from epistolary meditations on the nature of writing, to cutting put-downs and cheerful encouragement, were later to be gathered together into this lengthily-named book.

To a Seeker, from Kudowa

No, we don’t have any guides for writing novels. We hear such things appear in the United States, but we make bold to question their worth for one simple reason: wouldn’t any author who possessed a fail-proof recipe for literary success rather profit from it himself than write guidebooks for a living? Right? Right.

As of 2021, these collected letters of Szymborska saw publication in English, as How to Start Writing (and when to stop) translated from the Polish by celebrated critic, Clare Cavanagh, a specialist in Slavic literature. Cavanagh’s introduction to the work, sensible and intelligent as her translation itself, lays out for the reader some of the mysteries of the text. That, for one thing, Szymborska responded to her letters in the pluralis majestatis (the royal ‘We’) not out of haughtiness, but to keep both her gender and her identity secret, being the only woman on the editorial team. And that, for those in the rest of the occidental world fixated with the literary and artistic romance of an authentic and tragic Central and Eastern Europe, the reality for writers is still one of intermittent joy, crossings-out, and jottings in the margins.

To 71, from Otwock

The author must be wiser than his heroes, he must understand them better than they do themselves. Etch this phrase in golden letters on your soul before starting your next story. And remember: even future Nobel laureates get work rejected at first.

The text, as a whole, forms a pseudo-classical compilation of aphorisms and epigrams, a contemporary Ars poetica of practical and metaphysical musings. It’s also a minute sylwa rerum, a commonplace book of advice, anecdotes and letters, such as was kept by the late-renaissance nobility of Poland and Lithuania. These archival manuscripts — polonized from the Latin, Silva rerum — these forests of things with their leaves-on-leaves of contemplations, so many of which were torched during the six-year occupation beginning in 1939, echo faintly in Szymborska’s project. But, as its epistolary form is woven together, out of the scuffs, scratches and as-yet colourless bruises, rather than an insular act of documentation, comes to fruition something quite Rilkean. Her communiqués, spread out over the diverse multitudes of young poets, anthologise themselves until, much as Szymborska might oppose the concept, a theory of literary practice is thumbed together on the palette, to be applied to canvases (or notebooks) accordingly.

To Esko, from Sieradz

Youth is indeed a time of tribulations. And when authorial ambitions compound these troubles, an unusually sturdy constitution is required to survive. It must include persistence, industry, wide reading, powers of observation, self-irony, sensitivity, critical judgement, a sense of humor, and an abiding conviction that the world still deserves to exist, and with better luck than it has enjoyed thus far. The enclosed efforts demonstrate only the desire to write and do not as yet display the other qualities listed above. You’ve got your work cut out for you.

She can be anti-mammalian in her coldbloodedness, surveying the brownfields of half-constructed, shoddy, or derelict poetry, and its rundown companion in decommissioned prose

Wisława Szymborska, the bad-cop to the literary good-cop act of Letters to a Young Poet, is more of an anti-Rilke, than a disciple of the poet of Das Stunden-Buch. Her responses are sometimes like that of Rainer Maria Rilke, but through a glass, darkly. Rainer Maria Rilke if Letters to a Young Poet had been more critical, cynical, and perhaps, more honest. She is never flighty, though often-if-not-always witty. She can be anti-mammalian in her coldbloodedness, surveying the brownfields of half-constructed, shoddy, or derelict poetry, and its rundown companion in decommissioned prose: a gauntlet of peril for even the most patiently stoic or unoffendable among the literati. The wasteland sprawl of knocked-together monuments she curates seems enough to make any prospective writer doubt their life-choices. In turn, her cutting repartées are the brave parries of one who has already walked through the valley of the shadow of death. Her responses may seem harsh, but her criticisms are veiled insights, and her insights unveil depths.

To Ewa, from Bytom

Who knows, perhaps poetic powers lie drowsing in your soul’s depths. The fact remains that they have yet to surface. You impede them with heaps of clumsy metaphors piled so high that the world beyond them vanishes from sight. “Poeticity” is the reigning sin of novice poets. They fear simple sentences, they make things difficult for themselves and others. One in ten outgrows this phase and becomes a good poet; five quit writing completely; one switches to prose (with better results, we hope); while four keep fussing over ever more impenetrable poems. Looking back, we see our ten has suddenly become eleven. Another poet born every minute.

Her recommendations and conclusions are paternally Ecclesiastic: she seems to have lived through these vanities herself. And thus the conundrum necessarily arises: what authority is granted to Szymborska, and by what means? Did she follow her own advice? It’s easy to criticise, but the same can’t always be said of living by the aforementioned criticism. What seems transparent is that Szymborska is writing from a body of experience and not a Trojan horse: she hasn’t infiltrated herself into her position, she has constructed it through a lifetime that, though brief (as it necessarily is for all), has given her (as it necessarily does to all) a wealth of details, and in her hands a willingness and perspicacity to abridge them further into poetry. For Szymborska, though, writing seems not so much a matter of persistence or of skill, but of talent, without which there’s no absolute invocation to despair, but a warning not to heed the siren-call of GLORIA, LAVS ET HONOR chiselled on the imagined gateway of the bards, at the cost of neglecting the pale reality of study, humble interest, and near-monastic dedication.

To Elżbieta G., from Warsaw

“How can I teach myself Polish literature, especially poetry?” If you don’t have a high school diploma, then you should at least tackle the required curricula for literature and history. Pick up literary journals. Attend readings. Follow discussions. Seek out friends who read widely. A rather pleasant course of study, though it can’t promise immediate results. Such is life. Brief, but each detail takes time.

There are two afterwords to the letters. The first, titled ‘Pseudo-Afterword’ and written by Szymborska herself, describes the Orphic figure of The Editor, who, in his omnipotence, is solely responsible for the Literary Mailbox, who, in a Heisenbergian twist, is alleged to be vacationing in two places at once (Kashubian Switzerland and Warsaw’s Italian Quarter) and who, curiously, is described in the masculine: ‘He.’

He is tidy, pleasant, and kind. He adores animals, which alas can’t be guessed from the photograph. He prizes docility in women and pluck in men. He loves history and politics, but it is not mutual. He is exceedingly sociable, which comes more easily since he never reads his colleagues’ work. He is best known for a few experimental textbooks and a railroad timetable modelled on the avant-garde prose of Nathalie Sarraute.

The second is an October 2000 interview with literary critic, theorist and historian Teresa Walas, also included in Cavanagh’s translation. This is something of a respite at the end of a troubling odyssey. For readers daunted by Szymborska’s harsh-but-winged words, yet not discouraged by the wisdom they present, the interview helps to clarify that behind the curtain is not the Wizard of the Emerald City, but a real human person, themselves defending their own written efforts.

TW: You didn’t feel heartless at times, crushing some timid would-be-author?

WS: Heartless? My first poems and stories were bad too. I know firsthand the curative powers of cold water over one’s head. I was brutal, though, when anyone who claimed to be a teacher used “comparisen” in a letter.

The collection reads as a reminder, and the shooting pains and jolting whiplashes it induces will — no hay absolutamente duda — be best understood by writers, as they set about coruscating all they’ve written up to the present moment with such on-the-spot alacrity that they upturn the many writer’s guides they forgot to throw out, tossing down Szymborska’s book and wringing the sweat from their craniums with a guilty sheet of notebook paper. This seems exactly Szymborska’s objective. To prove that, though it might seem that the world’s creative impulses are by-and-large the recalcitrant dirge of rebellious mediocrity, beyond it all, in that promised land of perseverance, exceptions do exist. But first, they must be written.

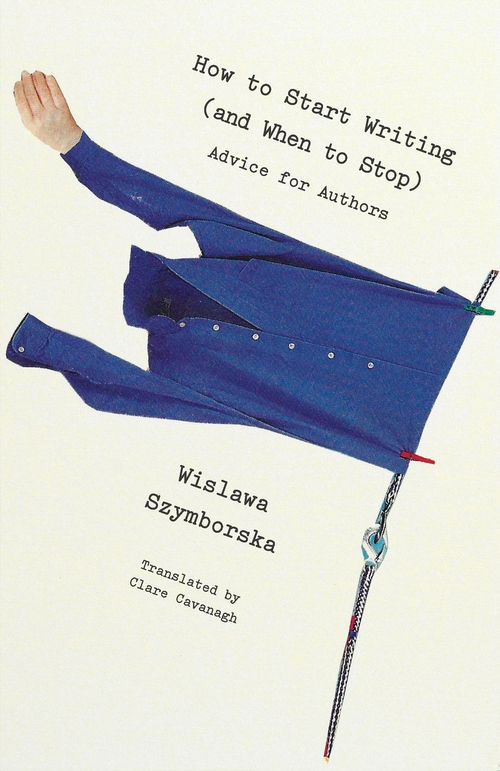

Wisława Szymborska: Well-known in her native Poland, Wisława Szymborska received international recognition when she won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1996. In awarding the prize, the Academy praised her “poetry that with ironic precision allows the historical and biological context to come to light in fragments of human reality.” Collections of her poems that have been translated into English include People on a Bridge (1990), View with a Grain of Sand: Selected Poems (1995), Miracle Fair (2001), and Monologue of a Dog (2005). How to Start Writing (and when to stop) is published by New Directions.

Clare Cavanagh is associate professor of Slavic and Gender Studies at Northwestern University. With Stanislaw Baranczak, she translated Wislawa Szymborska’s View with a Grain of Sand and Poems New and Collected; she is also the translator of Adam Zagajewski’s Mysticism for Beginners, Another Beauty, and Without End: Selected Poems. Cavanagh’s work has appeared in The New York Times Book Review, The New Republic, The New Yorker, The New York Review of Books, and other periodicals. She has received the PMLA William Riley Parker Prize and a Guggenheim grant for her work on Russian and Polish poetry. She is currently at work on Czeslaw Milosz: A Biography.

Joshua Calladine-Jones is a writer and the literary-critic-in-residence at Festival spisovatelů Praha. His work has appeared or is forthcoming from a number of journals, including 3:AM, The Stinging Fly, Freedom, The Anarchist Library, Minor Literature[s] and Literární.cz. His short collection, Constructions [Konstrukce] is available from tall-lighthouse.