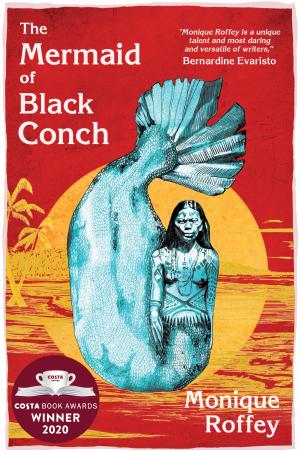

Monique Roffey’s sixth novel, The Mermaid of Black Conch, is set in a tiny Caribbean village in 1976. Attracted to the area by a fishing contest, an American tourist makes a remarkable catch: a mermaid, the victim of a centuries-old curse. The novel follows the battle for ownership of this mermaid, and the impact she has on the lives of the local people she encounters. Political, sexually-charged and brimming with energy, The Mermaid of Black Conch brings together many of the themes which have made Roffey such a compelling literary voice throughout her career.

Monique Roffey is an award-winning Trinidadian-born British writer of novels, essays, a memoir and literary journalism. Her novels have been translated into five languages and shortlisted for several major awards and, in 2013, Archipelago won the OCM BOCAS Award for Caribbean Literature. With the Kisses of His Mouth and The Tryst are works which examine female sexuality and desire. Her essays have appeared in The New York Review of Books, Boundless magazine, The Independent, Wasafiri, and Caribbean Quarterly. She is a Lecturer in Creative Writing at Manchester Metropolitan University.

Mermaids have been imagined by humans for thousands of years, across many different cultures – what did the figure of the mermaid mean for you?

The Goddess, per se, the matrifocal story of birth and of transformation and renewal, holism and transformation is really our first ever told story. It once had a central place in our early story telling. Slowly, this story was erased in the Bronze Age and replaced by the story of the hunt and the hero’s quest. The mermaid is a pre-Christian water Goddess. She is a 3000-year-old myth, first appearing in Assyria in the form of the Goddess Atagaris. She appears everywhere, though, in every ocean and some rivers: a woman who lives in the water. Humankind dreamed her up and imagined her all over the globe. The mermaid represents otherness, exile, blame, shame, beauty, sexual ambiguity, (having no genitalia). Many mermaids are associated with having a ‘sweet voice’, with singing, and most are young, and many are isolated, cursed and lonely. The mermaid represents so many ideas…..and of course I had started dreaming her too. She’s a complex loner, an outsider and a chimera. For all these reason I was drawn to writing about her.

The novel is set in 1976 – what was the significance of that time period?

I wanted a contemporary setting/time for the story, but not the 21st C. I didn’t want my mermaid to be captured on FB, Twitter and Insta, for example. I wanted there to be some doubt as to whether she had been caught at all, (everyone goes to the bar and gets drunk after she is caught, for example) and for the news story of her capture not to go viral within minutes….which it would if a mermaid was actually caught today and strung up on a jetty. Also, the Seventies was a time of uprising and revolution, especially in the Caribbean: Bob Marley, Black Power uprisings and of course feminism. Reggie, Miss Rain’s deaf poet son, has learned about deaf poems and has been given ideas about pride and community by a hippie leftie American teacher. I wanted the dawn of a Western and Caribbean social revolution to be part of the book’s backdrop. The Seventies in the Caribbean was a time of radical change in society, political thinking and across the arts. Cuba was communist and the Anglophone islands were no longer ruled by the British; there was self rule, black leaders, and a new era of nation building. And there were still big marlin in the sea to catch, too.

In the early stages of the novel, I saw some parallels with The Old Man and the Sea, and you’ve also mentioned Hemingway’s story Islands in the Stream, and Neruda’s poem ‘The Mermaid and the Drunks’. Was it important to you to be in dialogue with this masculine writing tradition?

Well, the Caribbean’s first canon of the 50s and 60s was almost entirely androcentric, so it’s hard to avoid referencing Caribbean literature written by men. I did see a photo of Hemingway standing next to three or four huge marlin in the Bahamas, and he stood proud. It’s a terrible picture. How dated it is now. They looked like racks of beef, or like human bodies strung up. I had that photo pinned to the wall while writing this book. And yes, there is massive catch scene in one of his books, which helped me with my own catch scene, e.g. just how long these big game fish hunts can take – hours – there’s ‘the strike’, then some skill in keeping the fish on the line, reeling it in, and then there’s ‘the fight’. Hemingway makes the whole event sound like a fearsome battle. So, while I hate all his big game hunting thing, I guess he knew what he was doing and writing about. And I didn’t. As for Neruda, his poem, The Mermaid and the Drunks, was also very central to how I imagined my mermaid. A man (Neruda) was writing about how other men might react to a woman like a mermaid running in to a bar for help. She would be violated. So I guess I have referenced men writing about their fantasies and ideas around this type of sexually ambiguous creature, a mermaid and /or a huge fish. Both are violated and dominated.

I found the character of Miss Rain very interesting, as a white Creole woman who is both socially liberal and the major landowner of Black Conch, living with the legacy of slavery which literally exists in brick and mortar around her. Is it important to you to show that tension between the character’s benevolence and her family’s legacy?

Bar the mermaid, all the characters in this book I know well; they are loosely constructed from people I know, including Miss Rain, the benevolent white landowner. I think the ‘evil white land landowner’ and the ‘crazy white mad woman’ are already well explored tropes in the Caribbean’s literature and both have become a little over typified. Miss Rain owns land and yet she is fair and also very much part of the island, from birth; her whole life has been lived there. She is of the island, a white island Creole. I know people like her. I know more than one white woman like Miss Rain.

Your mermaid, Aycayia, was cursed by jealous women; in the present day of the book, she is once again the subject of jealousy and hatred. Do you see this treatment of women as a constant throughout history?

Women have been so subjugated by patriarchy that we also internalise patriarchy. This can show up in the form of jealousy over men. It’s been around for millennia. The Aycayia legend is millennia old. So there must have been female jealousy then. We have this idea that our ancestors were in some way morally better and spiritually more connected to nature. But I don’t think we’ve evolved that much since pre-history. Women competed over men then and we still do. A young, beautiful and innocent virgin with a huge talent and who draws men to her in droves against her will (so the legend says) would activate jealousy in women then and now. Priscilla is ‘bad minded’, ‘born vexed’. She is a crusader for social justice, but she also has a huge blind spot too, or so I hope to portray, by making her zealous about making money from the mermaid.

There are parallels between Aycayia and The Tryst’s Lilah – both are symbolic figures of the mythic feminine – but whereas Lilah was a destructive force for Jane and Bill, Aycayia’s impact on characters like Miss Rain’s son Reggie and the fisherman David is more benevolent: David says she taught him to be a man, for example. Where do you see the divergences between them or their situations?

Lilah and the mermaid both act as catalysts. Lilah maybe be destructive, at first, but in a way she is also the making of Bill and Jane and she is the way Jane finds her dark side too and becomes whole. Jane ingests the part of her that is like Lilah. Or that’s how the novel ends. Lilah may be a wicked imp, but she has a positive long-term, holistic impact on a couple that are trapped in a sexless marriage. Aycayia, on the other hand, brings with her a shamanic purity and innocence. David knows no one like her and she inspires him to be good, or the best he can be. Both the mermaid and the imp carry transformative possibilities for the humans they meet. They are figures of old myth and have both been around for millennia. I’m not sure they diverge in any way. They are both part of pre-Christian mythology and represent a sacred feminine.

You’ve been very active in supporting Extinction Rebellion, becoming an organiser of Writers Rebel and hosting a series of events. What role do you think writers can play in political activism and bringing about cultural change?

Writers can and should join the climate crisis movement actively. XRWriters Rebel is a small Working Circle within Extinction Rebellion. We have been holding meetings, talks and actions around the climate crisis and we aim to galvanise writers and hold a space for them to come together. Our website will launch late March 2020. Many writers are already out there and have been for some time, e.g. Robert Macfaralane, Gregory Norminton and Joanna Pocock. Many writers are actively contributing to the debate. Many contribute to ‘green Twitter’ on a regular basis. Many are part of XR, as I am. The movement will grow, develop, and change; but it’s not going away, though. As writers we need to be developing new stories and a new language around climate change for the future. Writers, as culture bearers, can and should, inspire others, particularly the generations under us. It’s younger people, the ‘XR Snowflakes’, who are a massive driver in XR. Stories help heal humanity. I believe we writers need to be writing for the young, the old and for our planet.

Following on from that, do you see your activism influencing your writing in the future?

All my writing, to date, has been inspired by activism and been an act of activism. They are all novels which write about women, have female central protagonists, give agency to women, and Archipelago is an eco-novel. Should I keep writing, then I see myself as continuing this activism.