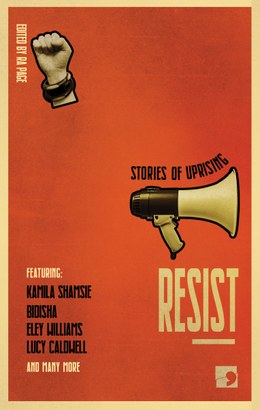

The Done Thing is an excerpt from the Comma Press anthology Resist: Stories of Uprising. In this new collection of fictions and essays, spanning two millennia of British protest, authors, historians and activists re-imagine twenty acts of defiance: campaigns to change unjust laws, protests against unlawful acts, uprisings successful and unsuccessful – from Boudica to Blair Peach, from the Battle of Cable Street to the tragedy of Grenfell Tower. Britain might not be famous for its revolutionary spirit, but its people know when to draw the line, and say very clearly, ‘¡No pasarán!’

Gran picks up a pair of heart-shaped sunglasses from the sea of crap on sale. The stall holder lifts a tiny mirror and smiles encouragingly.

Ben whistles, ‘Looking good Mrs A.’

Mrs A? Why has he started talking like The Fonz. He never talks like this when we’re back in America. It’s one of the hundred annoying habits Ben’s taken up since we arrived at Heathrow.

‘You don’t think I’m too old for them?’ Gran asks, tipping the glasses down her nose, doing her best Lolita impression.

‘You? Old? Never.’ Ben tries a pair too, with eyes shaped like flamingos. He nods along to the whiny Drake song from the stall holder’s phone. Ben’s being goofy, but Gran seems to like it, to like him. At least someone does. He’s gone down very badly with my dad the last few days.

‘Five quid,’ Ben shouts in a fake British accent, ‘bargain.’

Again, Gran chuckles. ‘Told you, it’s cheap here. Everything is cheap.’

She’s right, Dagenham Market is cheap. It’s also shit. I had forgotten that and now I can’t believe I suggested coming here.

They lay the sunglasses back on the tablecloth and walk ahead of me, arm in arm, past all the semi-decent things I want to look at; knock off handbags, vinyl, mini-doughnuts.

‘Do you have markets like this in America?’ Gran asks.

‘Of course there’s markets in America,’ I say as I catch up. ‘But where we live they’re a bit more artisan you know? Handmade soaps, truffles, limited prints, that sort of thing.’

‘Oh no,’ she says, ‘truffles. Sounds all a bit pretentious ’

Pretentious. She’s talking about me.

Gran slows, she’s getting tired. I take her other arm. ‘Are you okay? Do you want to sit down?’

She tuts, ‘Oh calm down. I can walk fine.’

‘Oh Mrs A,’ Ben throws his arm around Gran, ‘You would love Seattle. You’ve got to come and visit.’

‘Yes, I’ve always wanted to go. I do like Fraiser. They show the repeats on Channel 4. Was it really filmed in Seattle? You never know, do you? Like Eastendersis actually filmed outside of London. Cockfosters I think.’

‘Really?’ Ben says.

Even though he has no idea about Eastenders or Cockfosters.

We stop in front of a stall selling ‘bespoke’ furniture; a mannequin in a sequinned evening gown sits on a three piece purple velvet-effect couch.

‘Very posh,’ Gran says. But it’s hideous.

Maybe I am pretentious.

‘Ben, you’re right love, I could do with a sit down now. Let’s find the others and get a cuppa.’

They hobble off ahead to find Dad, who insisted on getting a chicken chow mein as soon as he arrived at the market, even though it was only half nine. He sits with his ‘new wife’ Elaine in the make-shift food court around a table covered in empty polystyrene bowls. Another Drake song plays through a tiny speaker propped against a large pan of jumbo prawns.

‘How was your breakfast son?’ Gran asks.

‘Perfect,’ Dad says as Elaine wipes at a yellow stain on his shirt with a paper napkin.

‘Didn’t buy anything then?’ Dad asks me.

I wish I bought something, to prove I’m not a snob. ‘I was going to get some toothbrushes, they’re so cheap here. But I didn’t have the correct change.’ I say.

‘Not your sort of thing anymore is it? Now you’re all living abroad.’

‘What’s living abroad got to do with buying toothbrushes?’ I ask, but hold off on asking him what exactly he means by it, I promised myself I wouldn’t argue with him this week.

Elaine leans across the table, showing too much of her freckly cleavage, and says, ‘I’d love to live in America, I’d get my teeth done.’ She runs a finger along her top row of teeth then drops out of the conversation to swipe about on her phone.

Dad nods over to Ben and Gran, their heads close to each other giggling about something.

‘1968?’ Ben says, ‘No way. You must have been a baby.’ And again Gran laughs.

‘What’s so funny?’ I ask.

Instantly she stops and her face falls back into neutral. How can she do that, go from vital and bright to pissed off and dull whenever I ask her anything?

‘Your Gran was telling me about her anarchist past,’ Ben says.

Gran slaps him on the knee. ‘Oh, stop it.’

‘What’s this about?’ I ask. But no one answers and Dad shrugs.

‘I didn’t know Ford made cars in England,’ Ben says.

‘They don’t anymore,’ says Dad. ‘We don’t make anything in England anymore.’

‘Right, shall we make a move?’ Gran wobbles as she stands and Dad rushes to catch her. ‘I’m fine. Stood up too fast that’s all. Blood ran right from my head.’

As we walk back to the car Gran falls behind with Dad and Elaine.

‘So weird,’ I say, ‘I never knew she worked for Ford. Can’t believe Dad didn’t tell us either.’

‘Sounds cool though. She said when all the women went on strike it brought the company to its knees.’

‘Yes, I know that,’ I say, frustrated with the history lesson. ‘Everyone knows that. They even made film about it. I just didn’t know that she was part of it. She never told me.’

But then she never tells me anything.

#

Downstairs, Gran sleeps propped up by cushions in an armchair, a half done Sudoku on her lap. I step close and put my face in front of hers until her nostrils flare slightly. She’s so still. Dad and Elaine are in the kitchen, whispering about something. Maybe they’re talking about Ben. About how much they dislike him. I creep towards the door but what I overhear is to do with appointments, injections and check-ups.

‘Everything okay?’ I ask.

‘Yep,’ Dad says. ‘Where’s Lover Boy?’

‘Asleep. He’s exhausted. The airbed kept waking us up last night. It deflates every few hours.’

‘Best I could offer I’m afraid.’ Dad takes the last bite of what looks like a ham and cheese sandwich. I thought when he remarried he would stop eating bread based evening meals.

Elaine, in her too tight vest and leggings, stands by the sink, tapping away on her phone.

‘So,’ I rap my nails on the table. ‘It was interesting that Gran was telling Ben about the Ford strikes right? I’ve never heard her talk about that before.’

Dad laughs.

‘What?’

‘Nothing, it’s funny how your accent keeps changing. You sound like him.’ He jabs a thumb up, then mimics ‘like, right, whatever you guys.’

‘I don’t sound like that.’

‘Yes, you do.’

‘Anyway, well,’ I stop and make a conscious effort to sound how I imagine my old self used to sound. ‘I’ve never heard Gran talk about Ford and the strikes before.’

But he’s not listening. ‘Elaine, can you make me another sandwich? Jam one this time please. There’s Hartley’s in the fridge.’

‘Dad, did you know?’

‘Everyone knows. There’s a film about it and everything.’

‘About her being involved. I never even knew she worked for Ford.’

‘Most of the old lot from round here worked for Ford at some point. It had the best wages in the area. It’s not a surprise. You’ve got to remember she was a single mum. She was always working. The chemist, the garage, the big Tescos, the mini cab station.’

‘Mini cab controller is the worst,’ Elaine says as she slops jam across four slices of bread, ‘I lasted about two weeks in that job. Couldn’t understand what most of the drivers were saying to me.’ She plops the plate down in front of Dad.

‘But to be part of the strikes must have been amazing. Don’t you think? I was reading about it. People credit it as kick starting the gender equality—’

‘Bloody strikes,’ Dad says, ‘Can you believe there’s another tube strike coming up? They walk out every time someone throws themselves on the tracks.’

‘That’s not why they strike.’

‘The teachers are the worst. They already get half the year off but they’re always pulling a strike about pensions. It’s ridiculous. You got a job, do it. Plenty people in this country desperate for work and can’t get it. Then the people with all the jobs don’t want to even show up to them.’

‘Tony,’ Gran’s voice from the living room calls, breaking him mid flow, ‘what you shouting about?’

Dad takes a bite from his sandwich and shakes his head, ‘Nothing Mum. Right, let me help the old bird to bed. I’ll leave you two ladies to chat.’ He walks out with the sandwich in his hand, leaving a trail of crumbs at which Elaine sighs before grabbing the Dirt Devil from the wall.

I don’t have a clue how to chat to Elaine. What can I say to try and bond us? To allude to what Gran did all those years ago so that women of my generation, which incidentally is also Elaine’s generation, could have equal rights at work.

The hoover stops and Elaine smiles at me, ‘She really appreciates you coming back to see her.’

It’s not true, Gran couldn’t care less if I’m here or not, but I nod along with Elaine anyway.

‘And it’s so nice that you’ve brought Ben here too. He’s very,’ she clips the hoover back onto the wall, ‘well Gran likes him doesn’t she? Bless her.’ Elaine glances at her phone, which sits blinking on the table. The conversation has officially died and it’s only a matter of time before one of us throws in the towel. ‘Do you play Candy Crush?’ she asks.

Online gaming. My worst nightmare. ‘Oh, not tonight. I’m a bit tired. Going to head up to bed.’

She smiles with relief and I go upstairs where I lie awake for hours on the wheezing airbed.

#

The next day all five of us are squashed on a bench at Leigh-on-Sea eating chips and drinking Ribenas. My diet always plummets when I come home. Carbs and sugar. Salt and grease. Surely, this kind of food can’t be good for Gran either, but she’s enjoying it, squashing the last of her chips onto the tiny wooden fork before raising her wobbly hand to her mouth.

‘Stop gawping at me,’ she says. She always catches me. It was the same when I was a kid, at her house after school, trying to watch how she cooked the dinner and ironed shirts. I didn’t have a mum growing up so figured Gran would be the woman to teach me what I thought I needed to know, but instead she would scold me for staring at her.

‘I was just thinking…’ I trail off.

‘What? Go on, spit it out.’

‘Well, I’m trying to work out how you got involved with the strikes?’

‘Oh, you do go on don’t you?’ She opens her handbag and pulls out a bottle of sunscreen.

‘No, I don’t. I want to know more about it, that’s all.’

‘Wish I’d never mentioned it now. It was only a strike. The film probably made it more glamorous than it was. Ben, here you go, put some Factor 30 on. You’re very fair aren’t you? My late husband was like you. People used to think he was Scandinavian.’

I lean forward, breaking her view of Ben. ‘I read a few articles about it. There’s loads online, I can show you. You might recognise some of your old friends. Maybe you could get back in touch with them?’

‘So, what was this strike for?’ Elaine asks as she begins collecting up everyone’s chip papers and handing out wet wipes.

‘Something about wages weren’t it?’ Dad says ‘The girls doing the sewing wanted a bit more money.’

‘Did you just say the girls? Dad, they were skilled machinists and the company paid them like cleaners.’

‘We only stitched seat covers,’ Gran says. ‘Ben, you look very distracted, what is it? Do you need a break from the sun?’

We all follow Ben’s eye-line out to sea. But there’s nothing other than brown waves.

‘Is that France?’ he asks.

Dad laughs, a big roar of it. ‘No, you silly sod. It’s Kent.’

‘Leave him alone, he’s foreign.’ Gran says. ‘Come on Ben, walk me up the road and buy me a stick of rock.’

He helps her up and together they walk off towards the small parade of shops while Elaine strips down to a bikini and sunbathes a few feet in front of us.

‘I think you’re making too much of this Ford thing,’ Dad says.

‘Why? What do you know?’

‘I know that women of her generation don’t like talking about themselves too much. Not like now. Women these days, they’re different aren’t they? Need to shout about everything all the time.’

‘Actually no, women are the same. We’re just speaking up more.’

He laughs, ‘I’ve noticed.’

‘What’s that meant to mean?’ I look back to the waves and try to calm down. I will not argue with my dad. I will not let him wind me up. I’m not sixteen anymore.

‘To be honest sweetheart, I don’t know where I stand with any of it.’

‘Any of what? Fairness? Equality? Women having a voice?’

‘Feminism,’ he says with a laugh. ‘I’m surrounded by women but still never seem to say the right thing. Complimented a girl in the office the other day and my manager came down on me, going on about sexual harassment.’

‘Oh come on Dad. This is ridiculous. Also, we prefer to be called women.’ I can feel myself losing it.

‘You’ve always been like this.’

‘Like what?’ I’m definitely shouting now, even Elaine sits up and looks back at us.

‘A little know-it-all.’

We sit in almost two hours of traffic on the way home, me squashed in the awkward middle seat in the back while Ben snores on one side and Gran hums off-tune on the other. The air-con’s on too high the entire journey and by the time we get back to the house I’m convinced I’m coming down with a cold. I wash the smell of chips and sea from my hair and climb onto the airbed, waiting for the slow process of deflation to begin. Ben clatters around in the bathroom for long enough to save me from having to pillow talk with him. But he wakes me up anyway. ‘Hey, I thought of something.’ His breath tickles my ear.

‘I’m asleep.’

‘Maybe something else went down with your Gran during the strike. It was London in the swinging sixties right? Lots of bra burning. Free love. Women standing together in solidarity. Maybe she had a fling with someone.’

I definitely don’t want to talk about this anymore. Not now.

‘She must have gotten lonely over the years. She told me she was widowed in her thirties. I didn’t know your Granddad died so young.’

So, she’s even spoken to him about Granddad. She’s never once spoken about Granddad with me.

‘Anyway,’ he carries on, ‘I told Gran we’d do an early lunch with her tomorrow. What time are we meeting your school friends?’

I can picture it already. Ben asking for vegan options at the pub, my friends smirking across the table at his accent and wondering how I ended up with someone so alien. ‘You know you don’t have to come tomorrow.’

‘Why wouldn’t I come tomorrow?’

‘Well, it’s just that it’s going to be a lot of talk about people you don’t know. Wouldn’t you rather do something touristy? I know you wanted to see the Tate Modern.’

He doesn’t say anything, but the sheets rustle as he turns away. When he speaks his voice is quieter, ‘You’re right. I’ll got to the Tate. Leave you to catch up with your friends. Night then.’

‘Night.’

Despite my earlier exhaustion, I can’t sleep.

#

Ben hardly speaks to me the next morning, except for some complaints about the British weather while he rubs Aloe Vera on the back of his sunburnt neck. Then he’s gone, without a goodbye, off to the Tate, just like I told him to. And I feel gutted.

Elaine is in the kitchen in her short-shorts, crop top and marigolds.

‘Morning,’ I say as I flick on the kettle.

‘There’s no milk. Your Gran’s gone to get some.’

‘Oh, I don’t drink cows’ milk anyway. Black is fine for me.’

Elaine runs the cloth under a tap, ‘I didn’t realise how smeared my cupboards were until the sun started shining on them. Filthy.’

I nod and make a kind of agreeable noise. ‘Do you mind if I put the radio on?’

‘No. Of course not.’

It’s a talk show, a caller passionately defends a Head Teacher’s right to ban skirts from its school uniform policy and I laugh. ‘Lucky them, I always hated my uniform. It was the tights really; I could never get on with tights.’

The front door opens and Gran comes in, she plonks the milk down on the counter and looks around the kitchen. ‘Where’s Ben?’

‘He’s gone to the Tate.’

‘What? What for?’

‘To see a world class collection of modern art maybe,’ I laugh, and she rolls her eyes at me.

‘Well, he could have told me. I thought we were going to the new café in the park together. I’ve got a BOGOF lunch voucher.’

‘Well, I haven’t gone to the Tate and I’m not meeting my friends till later. I can come with you?’

‘Oh,’ her face falls.

‘Actually Gran, should we have a walk up the high street first? Do some shops then lunch?’

‘No love, bit hot for that today. It’s already scorching out there.’

‘Okay, well I’m happy with the park café then. We could go early, have brunch instead.’

‘I don’t think they sell that. It’s mostly burgers and stuff.’

The kitchen falls silent and a caller explains how a genderless uniform will make transgender young people feel more comfortable. Elaine gasps.

‘What isthis drivel you’re listening to?’ Gran stands and switches off the radio.

‘It’s a debate Gran. People discussing issues that matter. Remember, you used to be interested in things like that?’

‘Right now I’m only interested in eating. Elaine, are you bothered about going up to this café? Bit hot to be walking about I think.’

Elaine snaps off her marigolds and throws them in the sink. ‘I’ve got some ham in the fridge, needs eating. I can make us a few sandwiches instead?’

I give up. ‘You know what, I don’t really fancy eating another sandwich, so I’m going to go up to the café by myself.’ I know I’m being stroppy and that I should rein it in. But I can’t help it and before I can calm down I’ve already slammed the front door leaving my phone and money behind. But I’m too proud to go back in and get them. So instead I walk towards the park and the café I can’t even eat in. Gran was right, it is hot and I feel my nose burning so hide under a tree. Two Romanian men sit on the bench opposite laughing with each other and sharing a bag of sunflower seeds, the ground below them is covered in empty shells. I remember Dad said the mess of sunflower seeds in the park was in his ‘Top ten reasons for voting Brexit.’

I’ve never agreed with any of them on anything, not Dad or Gran or Elaine or even the school friends I’m meeting later.

I miss Ben. I feel bad for how I’ve treated him, and for the fact that right now he’s probably looking at modern art with no one to make fun of it with. I can’t even message him.

When I get back to the house no one is there. I pick up my phone but I don’t want to apologise to Ben over text. I cancel my friends and spend the afternoon eating jam sandwiches and watching Made in Dagenham. It’s stupid but I find myself looking for Gran in it, for the woman she must have been, one so determined and full of will that she walked out of her job until the right value was put on her skill. But the women in the film are plucky and homely, all ‘saucy’ jokes and sixties clichés. I feel even more deflated.

Dad tries to call me a few times but I don’t pick up. Then finally, Ben calls and I rush to answer, keen to say sorry straight away but he talks first.

‘Where are you? Your dad’s looking for you.’

‘I’m home. Well, not home, I mean back at the house.’

‘Your Gran’s in hospital. She collapsed.’

#

I see Ben first and he grabs me for a hug, but I pull away, embarrassed that I was watching a film and eating Hartley’s jam from the jar while everyone was here, with Gran.

It doesn’t even matter but I have to ask him, ‘How did you know what happened?’ Did they call him before me?

‘I went back to the house to speak to you, then the ambulance arrived.’

Dad comes over and raises his eyebrows at me. ‘I tried to phone you.’

‘I’m sorry.’ I hold Ben’s hand, as if he can protect me.

‘What happened this morning? Elaine said you stormed out the house in a mood about school uniforms?’

‘Are you blaming me?’

He puts his palms up, ‘Don’t start an argument with me now. Go and see your Gran. She was asking after you.’

Ben lets go and nods me ahead, and I walk slowly down towards her bed at the end of the ward.

‘Oh Gran.’ I burst into tears and take her frail hand.

‘Stop it,’ she waves me away from her. ‘Sit down will you.’

‘I’m sorry. I’m sorry.’ I sit in the chair and pull a tissue from a box on the side.

‘I’m fine. It was only a fall, so stop bringing the theatrics in, alright?’ she lies back on the bed and puts the air mask on her face. The sound is slow, deliberate and long and I wish someone else was here now, to fill the silence.

She puts the mask down and rolls her eyes, ‘You’re doing it again.’

‘What? I’m trying not to do anything.’

‘You’re gawping.’

‘Sorry. I’m sorry.’ I’m useless.

‘So, how was the new café in the park then?’

‘I didn’t go. Well I did, but I forgot my purse. So went home when I got hungry, but you were all gone. I must have just missed you.’

‘Everyone was trying to phone you. But they couldn’t get through.’

‘I was watching Made in Dagenham.’

She chuckles, I actually made her laugh. ‘Oh, why are you so obsessed with this?’

‘Because you were part of it, and I think, well I think that’s so amazing.’

‘No, it wasn’t. It was ordinary. Ford was a rowdy place to work back then, there were strikes all the time. It was the done thing. Anyway, I would never have got involved with that one if I’d known.’

‘Known what?’

She sighs and turns away, up to the ceiling.

‘All those hours on that bloody picket line, standing there trying to fight for something I wasn’t even that bothered about. It was a job at the end of the day. I should have stopped working altogether and gone home to spend time with him.’

Him? I have to think about. The strike was in the summer of 1968, why hadn’t I made the connection?

‘Some of the women’s husbands were getting embarrassed, you know, that we were out on the picket lines. Especially when Ford shut down production completely and everyone was out of work. But your Granddad wouldn’t hear of it. He was a union man and really encouraged me. Believed in it and pushed me to continue. And then a week after we went back to work, he walked out in front of that van and that was that.’

‘Sorry. I never realised. I wouldn’t have kept asking if I did.’

‘Course not. You weren’t to know. Just like I didn’t know what was round the corner back then. You never have as much time as you think. Oh, listen to me, now I’m the one being theatrical. Here, pass me one of those.’

I pull a tissue from the box and look away while she wipes her eyes.

‘So, now you tell me something.’

‘Me?’

‘Yes, you. Why are you being so horrible to that lovely man you’ve dragged all the way here?’

#

I find Ben sitting near a bank of vending machines eating a Sesame Snap bar.

‘You know those things are over 50% sugar?’ I say.

‘It’s the only vegan thing I can find.’

He offers me a bite as I sit down next to him and for what seems like a long time the only sound between us is crunching.

‘Your dad gave me a very impassioned speech about the National Health Service earlier.’

‘Sorry about that.’

He laughs. ‘No, it was great; it’s the longest he’s spoken to me all week.’

‘I don’t know why I’ve been such a bitch to you these last few days.’

He puts a hand on my knee and I feel worse.

‘Ben, I’m sorry.’

‘It’s okay. Families make everyone act weird.’

I put my head on his shoulder and we sink back into the vinyl plastic chairs together.

‘You were in there for a long time,’ he says. ‘Did your Gran finally tell you what you wanted to hear?’

‘Yeah,’ I nod, ‘I guess she did.’

Luan Goldie is a primary school teacher, and formerly a business journalist. She has written several short stories and is the winner of the Costa Short Story Award 2017 for her short story ‘Two Steak Bakes and Two Chelsea Buns’. She was also shortlisted for the London Short Story Prize in 2018 and the Grazia/Orange First Chapter competition in 2012, and was chosen to take part in the Almasi League, an Arts Council-funded mentorship programme for emerging writers of colour. In 2019 she was shortlisted for the h100 awards in the Publishing and Writing category. Her debut novel Nightingale Point was published in July.

Resist: Stories of Uprising is out now from Comma Press.