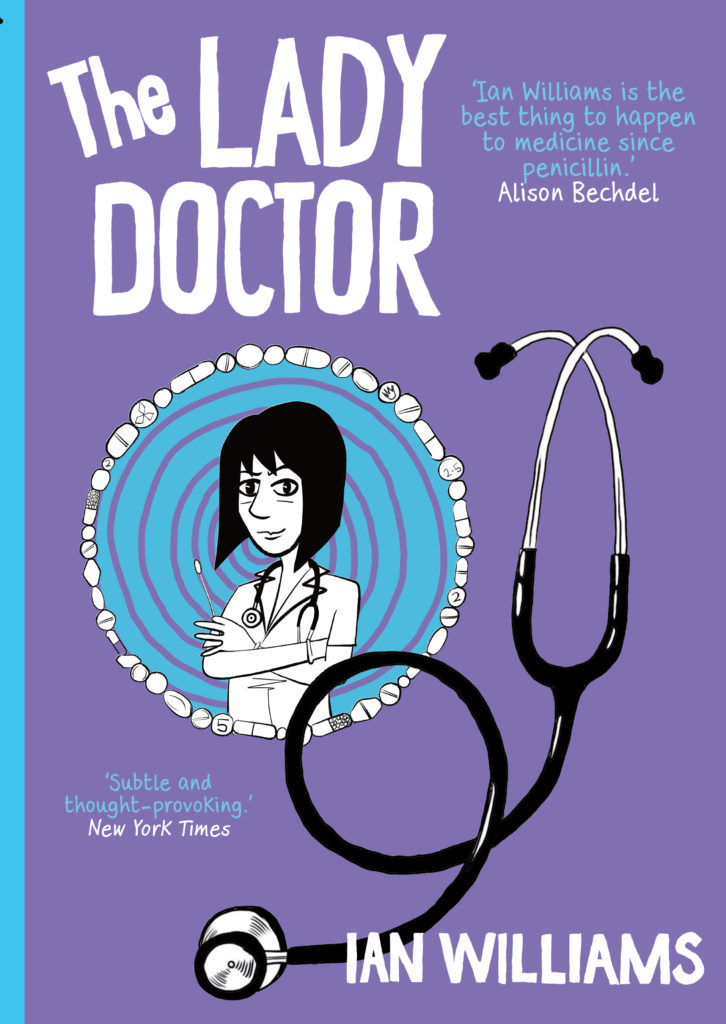

Ian Williams is a physician, printmaker and graphic novelist, whose attempts to fuse his various interests led to the development of Graphic Medicine, a new discipline which explores the use of cartoons to explore the interaction between cartoons and the practice of medicine. His latest work, The Lady Doctor, focuses on Dr Lois Pritchard, a single, 40 year old partner in a GP practice, who also works 2 days a week in a GUM clinic. The novel is a darkly comic look at current medical issues and the fragility of human existence.

The Momus Questionnaire was created by musician Nick Currie, and is designed to identify the aspects of the subject’s personality which give them a positive self-image, or ‘subcultural capital’.

***

Have you rebelled against someone else’s dreary expectations of your life, and become something more unexpected?

Yes, I think so. The teachers at school were skeptical about my chances of getting in to medical school. Then, when I qualified as a doctor, everyone expected me to have a conventional medical career: to work full time, marry another doctor, or a nurse, or a barmaid, make a lot of money, play golf or buy a boat, burn out at forty but keep working for another twenty years while hating my patients and family, etc. etc.

After medical school I went to art school and developed a side career as a painter and printmaker, then studied medical humanities, and started writing about healthcare narrative in comics and graphic novels. Then I became a graphic novelist, so my career has been odd, and twisty. I’m poorer, but I’d rather be doing this than working full time as a doctor.

What in your life can you point to and say, like Frankie, ‘I Did It My Way’?

I named a concept and helped found a movement – Graphic Medicine. I coined the term to refer to the intersection of the medium of comics and the discourse of healthcare and I set up a website. Without exaggeration, it changed my life. Ten international conferences later, we have a growing community and the term is in standard use, with numerous Graphic Medicine courses being taught in universities around the world. After naming the genre, I then created work that fitted within it.

The Lady Doctor is my second graphic novel.

What creative achievements are you most proud of?

My two books: The Bad Doctor (2014) and The Lady Doctor (2019). They involved insane amounts of work, and there were times that I thought I would never finish either one, but I did, and I am proud. I also drew a weekly comic strip in The Guardian for 18 months, which, while not my best work, gave me a certain amount of kudos at the time. In one of the strips I included a barcode which, If scanned, said FUCK THE TORY CUNTS. It was printed in the paper and is still online. That is something I am proud of. It always gets a laugh when I include it in talks, so I always

include it.

If there was one event in your life which really shaped you, made you the person you are today, what would it be?

Owning my history of mental illness. The Bad Doctor was a darkly humorous, semi-autobiographical tale of medicine, obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), cycling, and heavy metal. I suffered from a debilitating OCD from puberty until my late twenties, and still have the traits. I had never really discussed it with anyone and sought treatment relatively late (par for the course in people with OCD). I tried to hide it

through medical school and through my early years as a doctor, as medicine is a terribly judgmental and competitive profession where illness amongst colleagues– physical or mental – is seen as weakness. In autobiographical comics, however, illness, flaws and failure are currency. OCD is not about being punctual or tidy: the clue is in the ‘disorder’ bit of the diagnosis. For me it was a hellish decent into a tangled web of virally-proliferating thoughts and a general feeling of damnation; very dark and mostly to do with magic, religion and luck. I put a lot of my experiences into The Bad Doctor, but had not decided whether to admit that it was semi-autobiographical until I was asked by The Independent, if I would write an article about OCD. I thought ‘Fuck it. Let’s do it.’.

‘Coming out’ about it has felt good, and given me courage to speak freely about an illness that shaped my life. It prevented me from doing many things I would have liked to do when younger, and for years it stopped me from having children or committing to relationships (I cannot exactly regret this now, as I am married to a wonderful woman and have a two year old son who is everything to me). It probably had its benefits as well – I might not have become a graphic novelist if I hadn’t had OCD to write about. The condition shaped me, for good or for ill, but owning it,

making peace with it, is the more significant event.

If you had to make a song or rap boasting about your irresistible charm and sexiness, how would you describe yourself?

I AM irresistibly charming and sexy, I just don’t make a song and dance about it.

Have you ever made material sacrifices because of your integrity?

Probably, because I always try to avoid doing things just for money, or getting involved with things that I find ethically suspect, shallow, or in poor taste, but I can’t give you a unique, glowing example of flipping the bird at ‘The Man’, apart from the story of the barcode. I’m always ranting on about celebrities appearing in adverts for banks or payday loan sharks, or for fronting tacky lowbrow TV shows, but a comedian friend of mine pointed out to me that I do have the luxury of a bit, at least, of regular income (I work two days a week as a doctor) and added ‘Show business, innit? The clue is in the name.’

Most comics artists struggle to make a living, and anyone who tries to make a living from creative work has to market that work, or be marketed. I’m sure we’d all compromise our principles now and then if the family need feeding, it’s just a question of how close we get to selling our souls.

Describe a public personality who exemplifies everything you’d like to be yourself, then another public personality who incarnates everything you’d least like to be.

I’d like to be Leonard Cohen, but still alive. He was cool and interesting and complex, and he kept on going and updating his style without becoming embarrassing. In fact he started songwriting relatively late and became more successful the older he got. He was a poet, novelist, songwriter and a ladies man. He was a ‘lazy bastard living in a suit’. And he was Canadian. I’d like to be Canadian, right now.

The latter is easy: Trump, that odious dick-wad.

If you were an Egyptian pharaoh and had to be buried with a few key objects to take to the next world, what would they be?

So, I’m assuming I can take modern technology as opposed to ancient Egyptian gear? I’m temped to say, a fountain pen, an eternity’s supply of black ink and Papuro notebooks, but those other Pharaoh motherfuckers would would have armies and slaves and chariots, so maybe it would be more sensible to say a couple of tanks and a fighter plane.

Do you have a favourite joke, quotation or proverb?

I do, and I refer to it frequently. It is by the cartoonist Ivan Brunetti, from his book ‘Cartooning – Philosophy and Practice’ but it is apt for any creative endeavor :

“Although you have no control over the future, you have control over what you are creating right now, and if what you create is honest, it will be compelling. Whether or not it is truly good will be decided long after you are dead. But if you hedge your bets, compromise, prevaricate… you are lost. Something has to be at stake, a part of you that has to die and be reborn into your work, if it is to ‘live’ on that sheet of paper, cave wall or assemblage of pixels. In the end, all we can do is try our best. We are none of us perfect.”

What’s your favourite portrait (it can be a song, a painting, a film, anything)?

Possibly Meredith Frampton’s painting of Marguerite Kelsey (1928), which is in the Tate. It is just so beautiful, painted in a classical style with a subtle foreshortening and a brilliantly understated palette. There is nothing shocking about it, the work has an air of serenity. It looks very modern, considering it was painted nearly a century ago. The painting is calming and cool, reassuring in some way, but at the same time, it speaks of money and a cultural elite to which few would be admitted.