During one of his public speaking engagements, recorded as An Audience with Quentin Crisp, Crisp was asked how one could die with style. In response, he told the story of the Mexican revolutionary Sancho Panza. Gunned down during an armed uprising, Panza was found lying in a broken shop window. Rather than attempting to save himself, he merely said ‘Don’t let it end like this. Tell them I said something’. In The Last Word, Crisp muses ‘a significant death is a death which somehow gets into everybody’s mind so that nobody says “isn’t he dead? I thought he was dead”. You want to die in such a way that everyone knows and remembers your death‘. His own death was probably closer to Panza’s than he would have liked, but this final volume of memoir, published some 18 years after his fatal heart attack, allows him to make a final statement of his own, and it is an appropriately idiosyncratic and contradictory epigraph.

In his foreword to The Last Word, Laurence Watts eulogises Crisp in his later years as ‘an openly gay man who hadn’t been imprisoned and broken like Oscar Wilde, who didn’t take his own life like Alan Turing, who wasn’t associated with “boys” like Bill Tilden, who didn’t remain closeted liked EM Forster or John Maynard Keynes, who wasn’t disgraced like John Gielgud and who didn’t succumb to AIDS like Rock Hudson‘ – a gay man who had survived decades of oppression, triumphed by outliving his opponents, and lived out his old age in comparative freedom.

However, as Watts acknowledges, whether Crisp was ‘the kind of gay icon that the emerging global gay community wanted or needed‘ is very much up to question. His strongly individualistic viewpoints tended away from solidarity and towards reaction, while his contrarian nature led him to make damaging statements about AIDS and the abortion of homosexual foetuses in particular. Crisp’s fame was in large part a product of the era in which he lived: he put the success of The Naked Civil Servant down to the fact that, when it was first screened by the BBC, there were only two television channels available in Britain, providing him with a near-captive audience. It also ensured that he faced less scrutiny, compared to the omniscient media of the present day. In a 2013 blog post, Cathy Leech asked ‘if Quentin Crisp was on Twitter, would we all hate him?’:

‘Crisp was someone for whom it was inconceivable to admit he had been wrong. He privately made large donations to AIDS charities in his later years, after proclaiming to an audience in the 80s that “AIDS is a fad, nothing more”. But he never said sorry, or took it back. Which makes me wonder if he would have been able to resist the temptation to tweet similarly vile, offensive things, knowing that they would be so much more likely to trend on the back of a wave of outrage than any more benign witticism he could come up with.’

Interestingly, The Last Word is the only book which Crisp wrote because he wanted to, rather than because he had been commissioned. Unable to type, due to paralysis in his left hand, he dictated the manuscript, giving it the feel of a monologue. Crisp was aware of, and indeed welcomed, his imminent mortality; he maintained a frugal lifestyle, but had amassed over $1 million in savings, and had no immediate need of money. So what compelled him to work on this final document, at the age of 90?

In his second memoir, Resident Alien, Crisp noted that his public statements are ‘aphoristic, not in order to conceal my meaning, but because they have been made so often that they have become crystallized – if not fossilized’. Based on this, we may not expect much beyond the familiar witticisms which had become Crisp’s meal ticket. However, Last Words does bring something new for long-term readers. Crisp opens by discussing his identity, and making a remarkable declaration: ‘At the age of ninety, it has finally been explained to me that I am not really homosexual, I’m transgender. I now accept that’.

Watts refers to Crisp as ‘very much a victim of the time in which he lived’, not simply because his homosexual lifestyle was outlawed, but because there was little understanding of trans identity which could have helped him to make this identification sooner.

While there is some truth in this, and progress has been made in terms of access to information and online communities, it also overlooks the serious difficulties which trans people continue to face, with almost half of trans pupils in the UK having attempted suicide, and a resurgence of trans-exclusionary voices within the mainstream media, including nominally left-wing publications such as The New Statesman: trans people have not stopped being victims of the time in which they live. This idealised view of the trans experience mirrors Crisp’s own.

Looking back, Crisp says ‘My daydream as a child was of growing up to be a very worldly, very beautiful woman… I was in a terrible bind about who and what I was, something she [his mother] didn’t recognize or bother to think about’. Crisp had no framework within which to express these feelings: while he references trans pioneers such as Jan Morris, he had no awareness of them at the time, and reassignment surgery is viewed, even in retrospect, as having been an unattainable goal (‘had the operation been available and cheap when I was young… I would have jumped at the chance’).

It is deeply moving to read Crisp’s realisation of the suffering that this silence has cost him: ‘Had I been born a woman, none of my life would have happened and I could have been happy. Well, perhaps that’s stretching a point. Let’s just say I might not have been quite as unhappy‘. The effect of this new identification has a profound impact, breaking through the ‘fossilized’ layers of public statements and actions:

‘Now, for the rest of this book you will have to forgive me. Having labelled myself homosexual and having been labelled as such by the wider world, I have effectively lived a ‘gay’ life for most of my years. Consequently, I can relate to gay men because I have more or less been one for so long in spite of my actual fate being that of a woman trapped in a man’s body. I refer to myself as homosexual without thinking because of how I have lived my life. If you are reading this and are gay, think of me as one of your own even though you now know the truth. If it’s confusing for you, think how confusing it has been for me these past ninety years.’

As ever with Crisp, his views are not unproblematic, and his view of what life would be like as a woman is idealised to say the least (‘I would have gone to live in a distant town and run a knitting wool shop and no one would have ever known my secret’). In reality, the lives of trans women are even more threatened and marginalised than those of gay men.

At times, it sounds as though, more than anything, Crisp is longing for a non-queer existence. He fetishizes cishet identity, and has a corresponding disdain for those who fall outside of heteronormative categories – himself, and others like him: ‘I wish I had been born a woman, and one attracted to men, as I myself once was. That is my definition of real. It’s the reality I wished for myself’. This sentence reveals again the (understandable) messiness of Crisp’s position: as a trans woman, he had been ‘born a woman’, but not a cis woman – the only form of female identity which would have been ‘real’ to him. Crisp has gone from speaking as a homosexual with problematic attitudes on homosexuality to being a trans woman with problematic attitudes towards trans identity.

Further light is shone on this attitude as, finally, he shows some form of contrition for his controversial statements, acknowledging that ‘my views on gay sex may have also caused hurt in certain circles’. In particular, he attempts to clarify his opinion that mothers should be allowed to abort foetuses carrying a gay gene: ‘I didn’t want them murdered, I wanted them never to be born, which is different… what I was proposing was an act of compassion. I wouldn’t wish what I have suffered throughout my life on anyone‘. He explains this further through reference to ‘the context in which they were formed’:

‘My view of homosexual sex was certainly tainted not only by my experience in London as a rent boy, but by the times during which I was sexually active… with hindsight I would have been happier being celibate in a monastery than in degrading myself before strangers as I did. I thought it would bring people to me and that they would like me and they would be happy, but, of course, they despised me because their interaction with me made them ashamed’.

Again, one feels a sense of melancholy for this ‘victim of his time’. The queer subculture of his youth was proscribed and limited to hooligan cafes in Soho and all-male subscription dances, often held in rooms above Woolworths: ‘the events were held in secret, which means of course that everybody knew about it and they were always raided by the police’. By contrast, in old age, ‘I live my whole life unified by the fact that I can I can live in the outer world the way I live in my head. I couldn’t always do that and it’s a freedom I now cherish’. Not that he has any high hopes for the coming millennium: ‘If I had a vision of the twenty-first century, and I assure you I do not, I would have to say that things will generally get worse. That seems to me to be the trend that time is taking. Everything in my lifetime has become louder, cheaper, faster, nastier and sexier, and I don’t think it will suddenly reverse itself and go in the opposite direction’.

Mortality hangs heavily over The Last Word. According to long term friend and occasional amanuensis Philip Ward, Crisp had begun putting his earthly affairs in order, to the point where he had even ‘created a path from his front door into and around his room, a path that hitherto had not existed’. He confronts these imitations of mortality unflinchingly: ‘The truth is my body is dying on me. These days I carry it around like a horrible old overcoat‘. Crisp died shortly after The Last Word was completed, in Chorlton, Manchester, where he is commemorated with a series of murals.

The Last Word is a slim volume, which lacks some of the structure and style of his earlier memoirs, yet still allows a great insight into Crisp’s life. There is a remarkable clarity to the way Crisp narrates this final chapter of his life, even allowing for an element of digression. The work does not appear to have been edited significantly; there are some rather unnecessary footnotes, which don’t give much extra information about Crisp, but do helpfully explain that ‘Mr Shakespeare’ refers to William, ‘widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language‘. But why should we expect editorial intervention to bring us to a closer understanding of Crisp’s unique worldview? True to the title of his final work, we should allow Crisp the last word here. And so:

‘It seems to me that epitaphs and tombstones exist only for those who weep for the dead and bring them flowers. In which case, the perfect epitaph for me would be “I am not worthy”. Yes, that would be lovely’

Note regarding gendering: Although Crisp identifies as a trans woman in The Last Word, he also continues to refer to himself as a homosexual man, in line with the way he has lived his life, and does not specify any preference for an alternate pronoun. For that reason, I have continued to use the male pronoun in this review.

Quentin Crisp (Dec 25, 1908 – Nov 21, 1999) was an English-born writer, actor, eccentric and raconteur. He became famous from the publication of his 1968 autobiography The Naked Civil Servant, which chronicled the oppression he faced as a homosexual in England before, during and after World War II, when being gay was illegal, as well as his careers as a book designer, prostitute and artist’s model. The Naked Civil Servant later became an award-winning film starring John Hurt. Crisp performed a one-man show, An Evening With Quentin Crisp, which he toured nationally and internationally and which won an L.A. Drama Critic’s Circle award. Crisp moved to New York at the age of 72 where he wrote books on style, culture and manners, appeared in numerous films, published a second autobiography, How To Become A Virgin, and became the inspiration for Sting’s hit song, An Englishman In New York. In 1993 he became the first-ever presenter of Channel 4’s Alternative Christmas Message in the UK. Dinner with Crisp, whose telephone number was listed in the local telephone directory and who never turned down an invitation to dine, was often called “The best show in New York”. Frequently in demand from journalists as a social commentator, Crisp frequently proffered contrarian views.

Thom Cuell is unwell.

Image (Twitter): Thom Cuell

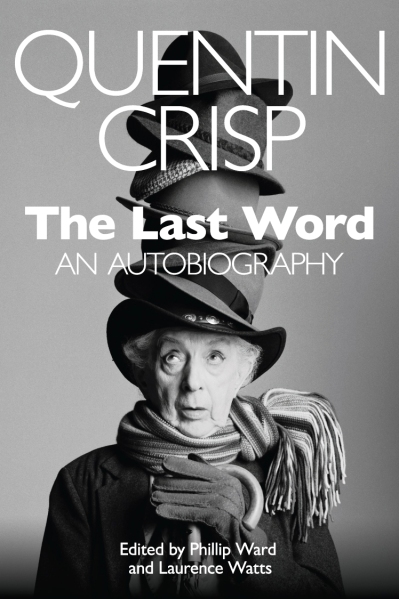

Image (book cover): courtesy of Laurence Watts

The Last Word is published by MB Books. Quentin Crisp biography courtesy of crisperanto.org