(On a Marxist poet, the Indian New Wave, biography, space, time and the ghosts of knowledge)

(Ranbir Kaleka, ‘Not Anonymous Waking to the obscure fear of a new Dawn’,

Single channel projection on multiple surfaces. c. Vadehra Art Gallery)

How does space, erstwhile imprisoned, suddenly burst open? Like the delinquents of Genet’s fiction that have so endeared themselves to us, languishing, anorexic, teetering on the cliffside of blasphemy and orgasm, sauntering in the dark of the night. This juxtaposition of darkness and revelation occurs as a long-delayed climax in the works of Gajanan Madhav Muktibodh (b. 1917), a poet-critic occupying an almost cultic status in the world of Hindi literature.

Space, time, the refurbishment of language

Having poured his life-blood into editing dead-end magazines, writing, erasing, re-writing, and engaging in conversations around the present and future of Hindi poetry, Muktibodh died September 1964, having expressed not only regret for a life spent in poverty and drudgery, but also resentment over the reception of his book, Bharat: Itihaas aur Sanskriti (1962). The Poet had found himself a wanderer on the margins of the movements that gained speed in the Hindi literary circles of the mid-twentieth century, an island unto himself. The lineaments of this self, however, were always caliginous, losing themselves in a darkness born of the collective.

There is no other writer of Hindi that comes close to Muktibodh in terms of uniting a vision of political commitment and interiority. However, it is in the aftermath of the failure of his political ideals that the self of the poet, distraught, hungry, blind, forges forward through the language of space and time, architecture, film, technology and civilization, to plumb the depths of the self. Consider this quote from a short story titled ‘The Bird and the Termite’:

काश, ऐसी भी कोई मशीन होती जो दूसरों के हृदय-कम्पनों को, उनकी मानसिक हलचलों को, मेरे मन के परदे पर, चित्र रूप में, उपस्थित कर सकती। उदाहरणत:, मेरे सामने इसी पलंग पर, वह जो नारी-मूर्ति बैठी है। उसके व्यक्तित्व के रहस्य को मैं जानना चाहता हूँ, वैसे, उसके बारे में जितनी गहरी जानकारी मुझे है, शायद और किसी को नहीं।

How I wish for a machine that would present the longings of other’s hearts, the movements of their mind, onto the screen of my mind, as images. For example: the woman-idol that sits across me on this very bed. I wish to know the secret of her personality, however, there is no other who knows her as well as I do. (Translation mine.)

Intimacy and alienation coexist, coalesce to form the arcane, the realm of the spectral, where ghosts as old as the advent of language live, breathe, and rot with their knowing. Muktibodh’s world proclaims: there is no knowing. This holds true for both the human sitting across from you, and the space that you inhabit, if only momentarily.

Spaces of tourism and tafreeh, not limited to the body

Urban middle-class sensibility is one of negotiation with space, inasmuch as it is not an outright condemnation of it. We allow only that which is proper, respectable to be seen and frequented. To bring to light the sewers filled with domestic and industrial waste, the haze of chemical emulsions from steel-plants, the whorehouses and the shady taverns—a labyrinth of a space yet unexplored—is not, of course, the task of those who live inside of it, but that of those who can write of, read, and engage with the narratives of its exploration, grapple with it as tourists engage with space, with a spirit of adventure, caution, ‘symbolic boundaries’, and the necessary promise of return. You shall not be held against your will. Wherever he goes, the tourist arrives at a mise-en-scène, an arrangement of objects in space that evoke, move, bother, but are ultimately removed from open view.

Mani Kaul, one of the provocateurs of the Indian New Wave, proclaimed in an interview on ‘Cinematography and Time’, that the execution of his cinematic vision of Muktibodh is a work of recognition. . Not creation, but a recognition, a sudden synthesis of meaning, in line with Walter Benjamin’s dialectical image that is as fleeting as a dream. The veil, as ‘tormented glass’, which one sees through darkly, at the altar of an image negating temporality, where space exists only in secondary relation to the image, while duration continues to be. The overtures of language to this image are many, all more or less futile when faced with the enormity of its being. These are the virtues of stillness: “It is only when the object and the camera are immobile (without motion) that we make an entire contact with duration” (Kaul on Kaleka, an artist and friend, whose Man Threading Needle consisted of projecting a video upon the still surface of a painting.)

Man Rising From The Surface: profane illuminations

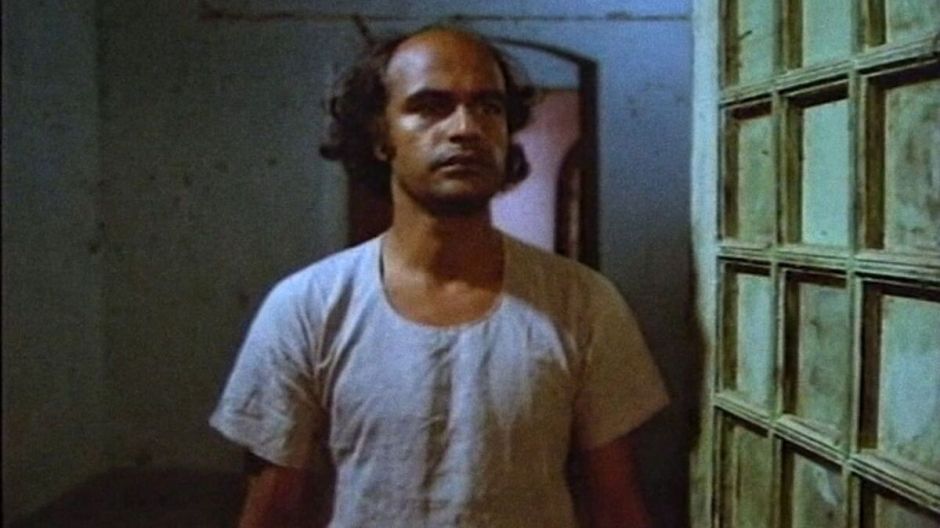

still featuring Bharath Gopi from Arising from the Surface, 1980

still featuring Bharath Gopi from Arising from the Surface, 1980

One thinks of Blanchot when viewing Mani Kaul’s film, Satah se Uthta Aadmi (Arising From The Surface). Publishing the fragments, letters, archives, etc. of a literary persona is an unveiling which “…would finally allow us to stop a dead voice…”, to exorcise, exhaust, empty the language fettered within the being now dead. Kaul is unapologetically Bressonian, and formalistic. Architecture and language. The language of architecture and the architecture of language as augury of space, where faces do not hold the key to meaning. (Kaul is equally dismissive about the face of the human and the inanimate.) To exist in his spaces, one must forego the individuality of revelation, and bask in flatness.

Types of flatness

- And when I am formulated, sprawling on the pin/ When I am pinned and wriggling on the wall// (TS Eliot)

The flatness of a full-frontal display, to be seen, gazed at, the clown in a room filled with an expectant audience who shout, perform for us!!! The face then becomes a point where shame, fury and humiliation are concentrated. In a book by Nirmal Verma, the narrator thinks of a childhood carnival; a retired clown tears off the rags of his costume, announcing: this is joy!

- Cézanne, non-perspective Mughal miniature, de-centred.

The stand-in for Muktibodh, Ramesh (played by Bharath Gopi), trembles within the labyrinth of his consciousness, the further he retreats, the sicklier he becomes. One sees the trembling poet move within domestic and industrial structures without reason or purpose, traversing the maze of his blundering mind on his feet. Space within projected without, the self, if it exists, is marginalised in both. Kaul says he is influenced not only by the absence of perspective in Mughal miniature paintings, where all that comprises a scene is given an equal splendour of detail, but also by the flatness of Cézanne’s paintings. The forms must refuse to be gazed upon.

Kaul, much like the poet himself, sees in the expanses of the city of Ujjain ample opportunities for what Benjamin calls ‘profane illumination’. Suddenness, which becomes a virtue in postmodern thought and exercise, presents itself within the otherwise ordinary, commonplace and mundane, transforming them into something else. But what if it is only the poet-protagonist who becomes disoriented, vertiginous (as is the condition of the modern literary man), and no one else…least of all the spectator-tourist, who, after closing the screen which displays the film’s only edition open to the public (a 320p YouTube video with echoing sound), returns, ordinarily, to a world Muktibodh spent his life critiquing?

The rolling stairs to darkness

Muktibodh’s critique is also directed at civilizational space, and the fatuous limitations it imposes upon those who inhabit it. In a story, he says, “…however, barbarianism is not as bad a thing as you take it to be. It has an instinct, a free-play of temperament, without hide and seek.” The Poet cannot come to terms with a post-socialist urban dystopia (Kaul’s film takes place in the foreground of a trade union movement and a thwarted Marxist revolution) in which the intellectual is banished, indeed why should he? Kaul recalls the question of Muktibodh’s writing: What is the poet’s role? Trapped in the post-Nehruvian state, which bears the marks not only of a recently post-colonized nation, but of partition, ethnocide, caste violence, illiteracy and poverty, the ruins of industries and socialism’s dreams, the rise of kitsch, populism and advertisement. The poet looks at a figure shrouded in darkness, sitting at the last steps of a stairwell, only to realise that the figure, perhaps, is himself and no other.

The revelations of knowledge, if they come at all, present themselves in darkness or ruins; the ruins of a factory, workhouse, bureaucratic offices, each as suffocating as the next.Or in wells and palaces haunted by the Brahmarakshasa, a mythic, malevolent being, a Brahmin-sage cursed to dwell in the mortal world as a monster. Much like Kaul, there is an absence of convergence in Muktibodh’s works, where the Brahmarakshasa becomes in one place a benign, grateful teacher, and in the other an obsessive, filthy being dwelling in the loathsome dark of an abandoned water reservoir. Two visions of knowledge—one that is, quite optimistically, passed on; and the other, more realistic, and truer to his vision, where knowledge, like all else, misused and distorted, festers as filth on a spectral body.

____________________________

Asmi Kartikeya is a writer based in Delhi, India. Her work has been published/is upcoming in RIC Journal & Sabertooth Magazine, among others. Find her on X @kafka_aise_kyun