Alienation was big in the twentieth century. Marx had a lot to do with it, but the despair went beyond the growing distance between labour and product—which was only the first measure in a devastating diagnosis of social ennui, ranging from our alienation from our own essence to our alienation from one another. Everyone along the political and sociological spectrum was considering the psychic effect that sent the masses into their own internal abysses, from Frantz Fanon to Robert A. Nisbet, which is to say: even if you weren’t an acolyte of the reds, it was difficult to escape the idea that societal fractures were growing more chasmic and irreducible with each major event—each war, each protest, each resetting of borders, each regime change. People changed in different directions, and in finally acknowledging that membership of the same class or race was not enough to hold us together, we required new understandings of how there could be such drastic bifurcations between people that looked alike, worked side by side, or lived in the same home. The badly hidden began articulating itself right at the urban surface (as in overarching senses of powerlessness and meaninglessness), and previously tolerable discordances became sharper and less repressible (as in intergenerational conflicts and shifting values). Human drama was forming around a more explicit cultural estrangement, in which one was increasingly liable to feel out of pace with the time, the culture, and the people they were supposed to love.

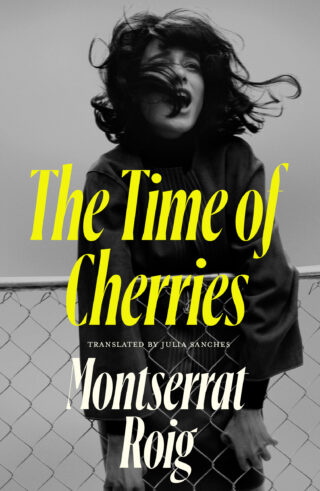

Montserrat Roig’s The Time of Cherries was written in its original Catalan in 1974, only one year before the end of Francoist Spain. For over three decades, the dictatorial state had ruled with unvarying brutality to enact its nationalist vision, which included devastating repressions of plural languages and cultures in the Basque Country, Galicia, and Catalonia; by its waning years, however, the Falangist agenda in the latter had shifted from total oppression into the co-optation of Catalan culture, activated in service of further legitimising the regime. It was simply a camouflage of autocratic violence with technocratic pragmatism, seeking to rein in the region’s conservative sectors for the regime’s own perpetuation, but if one squinted one’s eyes, it appeared that a spirit of “tolerance” had won over oppression. It is amidst this deeply conflicting, fundamentally imperialist limbo of Catalan life that Roig’s intergenerational tale unfurls, across the many divides that crack open along a single family tree. While the furious engines of political turmoil growl in the background, Barcelona swells here with nouveau-riche frivolities, heart-pounding protests, rotting palatial estates, Tupperware parties. Yet, in Roig’s clear-eyed descriptions, this turned-up urban volume ultimately defines its torn-apart city as one of loneliness. Amidst the fall-out of war and authoritarian ruthlessness, people tunnel down vortexes of memory, evade exchanges of any depth, and take long walks alone. Translated with mesmerising vividity by Julia Sanches, the fluid prose diffuses into these characters and their respective isolations, throughout dinner gatherings and doctors’ offices and police stations and crowded bars. They carry their thoughts, their legacies, their memories of pleasure and of unimaginable pain as if public life must be held at a very low volume. But inside blare songs. . . screams. . .

The clan at the centre of The Time of Cherries are the Miralpeixs, an old family with a prestigious legacy. And though much of their surname’s glamour has dissipated, this aristocratic ghostliness tails its heirs like a ruined shadow. It’s telling that the Miralpeixs have one enduring trait: heavy, dark bags under their eyes. Having long abandoned a grand, rural estate in Gualba for the central Barcelonan district of L’Eixample, the two scattered generations that make up Roig’s varied cast are the now-aged patriarch, Joan Miralpeix, his sister Patrícia, and his two children, Lluís and Natàlia—along with Lluís’s wife, Sílvia. Through the omnipotent third person, each of these individuals are in turn illuminated, their psychic landscapes explored, and in this myriad approach, one is afforded a multivalent view of the long-ranging animosities and simple differences that have drawn the family members further and further away from each other. Though there are certain pivotal incidents at the heart of these fractures, it quickly becomes apparent that their isolation cannot be pinned down to any event. Instead, as with any timeworn familial wound, there seems to be a lifetime of growing apart, rejections, misunderstandings, perceived betrayals, lack of sympathy. . . Or perhaps an impassable distance has always been there, instantiated by the lessons that each generation takes from their tumultuous decades.

Having left Barcelona in a self-imposed exile twelve years prior, the story opens with Natàlia’s return. She does not know why she’s going back, only that she must. Two days before her flight, a shattering piece of news arrives: the Franco regime has just executed the anarchist and liberationist Salvador Puig Antich in a malevolent reprisal against the struggle for Catalan independence. Natàlia is devastated—but not only by the young militant’s murder and the resulting shocks sent across Spain: “The problem is that [she] had left the same year as the miners’ strike in Asturias . . . and as Grimau’s arrest.” In naming the legendary Communist leader who had secretly operated against the regime, Roig draws a parallel between the first and last years of Franco. Julián Grimau García was arrested for “continued rebellion” on November 7, 1962 and given a farcical trial in military court; despite overwhelming outcry from the international community, he was executed by firing squad at the age of twenty-five, only five months after his arrest. History has named him as the last person shot in the Civil War.

From the intensity of this opening chapter’s historical context, one could assume that Roig has written a novel dense with the furtive, heated politics of life under dictatorship. Instead, The Time of Cherries taps into the vein of a city that does not know how to keep struggling, as the present has converged on being almost bearable. One is reminded of Herbert Marcuse’s indictment of false liberations, which “encourages . . . letting-go in ways which leaves the real engines of repression in the society entirely intact, which even strengthen these engines by substituting the satisfactions of private and personal rebellion for . . . a more authentic opposition.” The most devastating of ruling powers have always counted on superficial leniencies to prevent overwhelming dissent, manufacturing a complicity that comes in the shape of complacency; in the years prior to Natàlia’s homecoming, pedestrian life was no longer threatened by the overwhelming hunger that defined the first decade of Franco’s rule; strategies of economic improvement had been rolled out to placate the business elite; and even the state’s National Literature prizes were open to entries from the Catalan language, for the first time in nearly thirty years. . . But all the while, the state was putting their muscle behind eradicating the Communist Party, fuelling entities of de-politicisation, encouraging people to look the other away. Roig chooses to explore the pulse of this time via its aftereffects—by how individuals have absorbed and navigated these radically shifting years, in which comfort has been redefined into something that is just slightly better than terrible; opening with Antich’s execution is a brute awakening to the masses who have sank into lethargy. In the words of W. I. Thomas: “If men define situations as real, they are real in their consequences.”

When Natàlia returns, she is still unsteady at the thought of seeing her brother and father, so intead opts to stay with the aged, long-widowed Patrícia. Roig lets the hurts of the family unravel slowly, letting out hints here and there (Lluís thinks that Natàlia has arrived to “stir the pot”), but soon the pieces are put together. In her youth, Natàlia had gotten involved with the resistance—and one charming Communist named Emilio in particular; this potent combination led her to a very brief stint in police detention and an illegal abortion that took a devastating turn. The former strained her relationship with Joan, while the latter shut down any closeness with Lluís. From Natàlia’s side, her father and brother are people who seem to care of nothing but making money and shutting themselves away from the world’s open wounds, while she herself has at least opted for a wandering aimlessness instead of a hardened stoicism. Having grown up in the shelter of an upper-class upbringing, she was shellshocked when Emilio first exposed her to the wreckage that is Barcelona, dizzy from misery and grime. In the pervasive gesture of young men seeking to educate an ingenue, he had taken her to a working-class neighbourhood, taking care to define a “left-wing Falangist” and a “xino” (“What does that mean? she asked. A xino is a communist.”). But after a traumatising evening at the mercy of the state, juxtaposed by the torture going on elsewhere, and sharing a cell with the dispossessed whom she could’ve spent her whole life overlooking, what she derives from this clarifying episode is that nothing changes, “whether you’re in here or out there”.

She couldn’t have known that her father had travelled along a similar trajectory of youthful idealism and bitter awakening—but we do. Rejecting the feudal lordship of his own father, Joan Miralpeix had preferred to sit in front of an aperitif, “discussing art, literature, politics, and of course, their hopes and dreams for a better world” with his friends. He romanced the mother of his children, the peculiar and striking Judit, who upon seeing rosebuds, “tittered like a bird”, and there was the beautiful reprieve of love that united life with his vision of poetry: “The way Huxley tries to reconcile physical and spiritual pleasure.” But then the war came, and with the war a need to strip one’s selfhood away, to lose logic in the dirt and exhaustion of combat and to sit in a concentration camp writing letters that stated, in a language foreign to him, the things they needed to hear—dismissing his own past convictions as “Commie nonsense!” His friends were executed, sent off to extermination camps to starve. Judit went to political meetings and was convinced of a Republican victory, but when the smoke cleared for the Nationalists’ arrival, she too learned that she was not brave.

The word “change” appears again and again throughout The Time of Cherries: hoped for by those who have the stomach for hope, gazed at with suspicion by those who have sidestepped responsibility, reneged on by those who have seen enough to know better, pushed off on the young by the old and tired, ignored by those who have other priorities in mind, and sitting with the weight of so many alternative worlds on those who still seek its vague promises of absolution.

By the time of Natàlia’s return, the Miralpeixs have all gained plenty of reasons to avoid politics; their motivations are indicative of individual personality, but still carry the strong flavour of their respective milieus. Patrícia and Judit are repelled by the suicide of their revolutionary friend; Sílvia harbours the marks of Catholic punishment (a dominant aspect of Franco’s Falangism); Lluís has a faith in technology that is apropos to the advancing industrial civilisation, claiming that “both the right wing and the left [are] a plague that ought to be stamped out”; and Natàlia and Joan. . . They can’t bring themselves to forget, and they can’t quite move on. No one has the drive or the attention to fight for much of anything—let alone a new reality—but the fires are being stoked just to the side of the narrative, and something is running its course. Roig is not a writer who is cynical about the prospect of change; the author knows the dictatorship will end, but she also knows that there is no momentous victory waiting to be celebrated. Francisco Franco died peacefully in bed in 1975, and his funeral was very well attended; his remains were sent to the Valley of the Fallen and given a hero’s burial (they were moved out only in 2019). Spain then instated their infamous pact of silence, and much of the regime and its aftereffects were dealt with in the peoples’ own alone ways. Having the historical facts in mind, Roig aims at the psychological effects of endurance, of an utterly private frustration that cannot be articulated. It is a portrait that has never ceased to be relevant: someone who knows that things should be better, but can’t actually allow that feeling to overtake their everyday lives, their patterns and menial pleasures. Between Joan and Natàlia, she suggests that we all carry a certain threshold for disappointment: that when we are proved wrong enough times, when the things we build keep crumbling down, or when the most quixotic amongst us are sent to their deaths, we reach a state of despair that we translate pragmatically into complacency. We find other things to care about—marriages, careers, beauty, trinkets—which are simpler in their fulfilment of needs, and we displace ourselves into the bystanding role to observe only our own uncontrollable aging. It posits an interesting theory regarding cynicism: that we are not jaded because we grow older, as the younger generations are wont to accuse their predecessors, but simply that we get jaded and we get older, at the same time. One civil war followed by three decades of dictatorship is enough time for a minimum of two generations to be profoundly affected, but the inability of Joan and Natàlia to come to an about-face—to diagnose the dictator-shaped hole in the middle of their bitterness towards one another—is based more in their similarities. First with faith, then the obliteration of that faith, they experienced the same limits of human autonomy; what’s crucial is that they came to their revelations in different decades.

Karl Mannheim, in “The Problem With Generations”, posited that history is shaped by independent social dynamics that have to do with “individuals who come into contact anew with the accumulated heritage”, which results in “a novel approach in assimilating, using, and developing the proffered material”. These novel approaches are not only affected by our individual generations, but on how the trajectory of life moves differently for us all. Some of us go from one country to another; some go from one class to another; some get married or have children; some don’t. It’s not the number of lived years that leads people to have divisive understandings of political matters, but a variance in how and when societal change meets up with their individual experience—which are often (though not always) tied up with age. For the people who have personally lost a war, they perhaps have little patience left for those who believe they are still fighting it. For those who are still urging for a better future, it may seem ridiculous that one loss should lead to complete forfeiture. When it comes to the possibility of something as momentous and temporally specific as social or political revolution, any resurgence can act as a reminder of past failures; there are those who can keep the spark of political consciousness going forever, but in many more, this initial conviction will wane, and the appearance of it in someone else can incite a judgment of naivety. That familiar adage of parents comes to mind: I don’t want to see you making the same mistakes.

Therein lies the need to distinguish memory from history, and the vast discrepancy in how the past is organised in each mode. When one experiences a social event through the channels of memory, the present is expanded in accordance with what one already knows, whereas history tracks verifiable actualities in order to progress its own linearity; the function of memory is to forge internal connections, and the function of history is to replace personal experience with surviving absolutes—to forge a single, true, and universal “memory”. For those of us who learn the past through history, it is automatic to diminish those who hold on to it through their own recollections; they seem limited, defensive of a single perspective. As for those who remember, it may very well feel like that history has abandoned them altogether.

The lack of memory, when it is relinquished into history, has disastrous consequences of alienation; with the wealth of data that has become increasingly available and the technologies of historical preservation well-established, memory has never been so neglected and impoverished. Even what we recognise as remembrance today is quickly sublimated into the greater plot of history, as Pierre Nora warned: “. . . we should be aware of the difference between true memory, which has taken refuge in gestures and habits, in skills passed down by unspoken traditions, in the body’s inherent self-knowledge, in unstudied reflexes and ingrained memories, and memory transformed by its passage through history, which is nearly the opposite: voluntary and deliberate, experienced as a duty, no longer spontaneous; psychological, individual, and subjective; but never social, collective, or all encompassing.” Essentially, memory is no longer in service of uniting us, because it has chosen to marry itself to material evidence: to photographs, documents, recordings. In attempting to create a comprehensive archive of human behaviour, we chip away at the instinct to find humanity in the lives around us. We become more liable to treat each other like symptoms of a generation, basing our definitions on a contemporary evaluation of the past. We reduce one another’s consciousness.

Society has an unlimited array of factors by which to change; people—they might go through all sorts of things, but they mainly go from young to old. It may seem simple then, to characterise the aged and the youthful with the qualities that they most commonly display, and our language has even adopted a generation-based shorthand by which to immediately compartmentalise—but in order to validate our individuality, we must allow memory to complicate history in a way that destabilises meaning and intergenerational regard. Should the immense proportions of time be queried not through solid forms of identity but the ever-changing dynamics of relationships, we would be better poised to locate ourselves in the midst of great change. As such, reading The Time of Cherries in present day is a ride of great sorrow and a strange journey of various empathies, which feels particularly potent in an era where most of us have experienced some kind of dinner-table political blow-up with someone we love. When the world feels on the verge of transformation, there is mounting frustration when one is met with apathy or a lack of solidarity—or even worse, disparagement or mockery—from the various generations of one’s familial line. Such fracturing of intimate relationships lead not only to a psychological isolation, but a decisive break in one’s own line of memory; the sense of betrayal is compounded because the self is left stranded amidst the unseeing facades of history.

Towards the end, Natàlia takes a long walk with her nephew, Màrius, the young son of Lluís and Silvía. She meets his friends, who talk about The Rolling Stones and seductive poetry teachers. One of them dreams about having seven children, and a surprised Natàlia comments, “You want children while we did everything not to have them.” The girl responds easily: “That’s because you’re the pill generation. . .” Later, Màrius confesses his desire to follow in his aunt’s tracks and to run far away, to which Natàlia gives the best advice that she can: “. . . but then I left and realised we carry the city inside us.” It is a wistful chapter that insinuates some subtle shuffling of the ranks, as the old guard is being replaced by the new. Different dreams but similar desires, different tastes but similar impatience, all borne anew. Out of the need to pinpoint oneself amidst the flow of the era, we must discern the differences between ourselves and those who came before, but at some point, we become the subjects of someone else’s difference. In the beginning of the novel, Natàlia describes herself as “the reluctant daughter of Francoism”, but here she’s an incarnation of “the pill generation”. The many insufficient little labels we adhere to our predecessors, our successors, and ourselves.

I wish that there could be a way to take a comprehensive survey of all the readers of The Time of Cherries, to see which characters resonated most with various age groups—although I have the feeling that the findings might not be so neatly portioned. Having recently entered my thirties, I initially sympathised with Natàlia, discerning that familiar current of repressed rage and common cowardice, but also recognised something of Màrius’s subtle blend of hopelessness, deep dissatisfaction, and propellent dreaminess. I got Silvía too, the way her boredom and thwarted ambitions made a crepuscular, almost unfathomable puddle in the centre of her mind; and Patrícia, who fell into one thing and then another, with always a glass wall between her and her desire. Finally, it was Joan—exhausted, defeated—who saw the worst and still lived, who saw the false promises of freedom carved across the history of his choices, whom I saw so clearly. Those faraway eyes.

With an approach that is uninterested in generation as signifier, The Time of Cherries posits the perceived divide as the veneer on top of a much more unfixed narrative—one that forms a connective tissue between the separate groups, instead of insisting on their mutual unintelligibility. One is guided into loss by arbitrary divisions that deny us the holistic comprehension of a shared world, shutting off the portals by which we may communicate with one another across divides, and the enduring role of storytelling is to once again reconnect our disparate alienations to the overarching repressions that dictate them—to visualise a separate position and see the ways in which it could resemble our own. As Foucault once said, “It is possible that the struggles now taking place and the local, regional, and discontinuous theories that derive from these struggles . . . stand at the threshold of our discovery of the manner in which power is exercised.” Generations are often spoken of in the language of succession—one “takes over” the other—but the reality of the situation is that nothing is simply handed over, and no one is displaced into disappearance, no dimension is lost. The narrative extends, growing more multiple and more complex, and our methodologies of resistance and conceptualisations of liberation must also grow to meet it—that is, if we are ever to feel less alone.

Earlier in the year, as students across the world courageously mobilised against the genocide in Palestine, my father rolled his eyes as he said to me, “They’re getting all worked up for nothing.” It made me think: if the notion of solidarity is separating from the family module in times of political difference, perhaps there is a different role for the family to occupy—one that doesn’t necessarily stand with us in our pursuits of a better future, but that can fill up the gaps in the story. It is, after all, the story of oneself. I opened my mouth to retort with something along the lines of you don’t know what you’re talking about, but then remembered that in the spring of 1989, he was in Beijing.

Montserrat Roig (Barcelona, 1946-1991) was an award-winning writer and investigative journalist. Her journalistic work focused on forging a creative feminist tradition, and on recovering the country’s political history. Her novels take similar stances, reflecting on the need to liberate women who were silenced by history. Her first novel Ramona, adiós, published in 1972 has become a cult hit and is considered one of the greatest Catalonian books. The Time of Cherries is published by Daunt Books.

Julia Sanches is a literary translator from Catalan, Portuguese, and Spanish into English. Recent translations include Living Things by Munir Hachemi and Mammoth by Eva Baltasar, both finalists of the Cercador Prize; and Reservoir Bitches by Dahlia de la Cerda (co-translated with Heather Cleary). Her work has been supported by multiple grants and residencies, including ArtOmi, the New York State Council on the Arts, and the PEN Heim, and she has been longlisted and shortlisted for several prizes, among them the International Booker, the National Translation Award, and the PEN Translation Award, which she won in 2022 for Mariana Oliver’s Migratory Birds. Born in Brazil, she now lives in Providence, Rhode Island.

Xiao Yue Shan is a poet, writer, translator, and editor. Born in China and living on Vancouver Island. then telling be the antidote won the Tupelo Press Berkshire Prize and was published in 2024. How Often I Have Chosen Love won the Frontier Poetry Chapbook Prize and was published in 2019. She is one of the editors and translators of Ten Thousand Miles of Clouds and Moons: New Chinese Writing, an anthology published in 2025. shellyshan.com