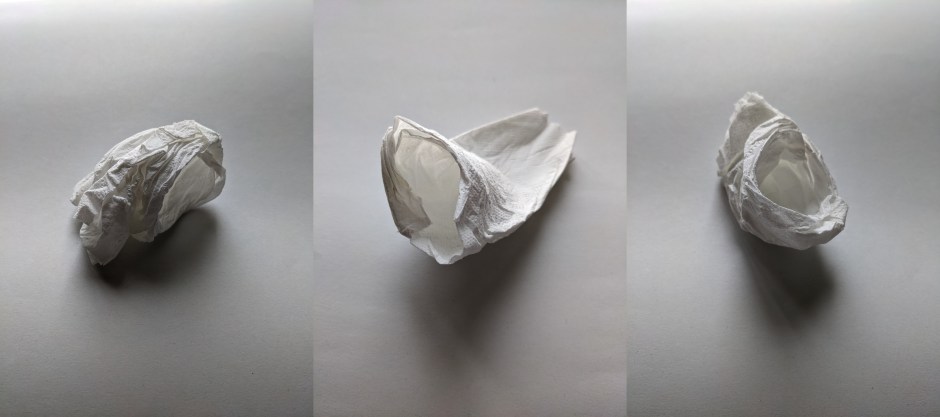

Pádraig Ó Raghallaigh: Three Studies for Figures at the Base of an Extinction Event (after Bacon), 2023, digital photographic triptych, (moulded tissue paper)

Pádraig Ó Raghallaigh: Three Studies for Figures at the Base of an Extinction Event (after Bacon), 2023, digital photographic triptych, (moulded tissue paper)

Pádraig Ó Raghallaigh’s 2023 triptych Three Studies for Figures at the Base of an Extinction Event (after Bacon) repurposes Francis Bacon’s 1944 triptych Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion for a 21st Century marked by biodiversity loss, rising sea levels, ecological breakdown, resource depletion, and a global pandemic.

With various neurological disorders under his belt, Ó Raghallaigh’s artistic practice embraces the bitterness and disillusion of a career spent labouring in the margins of cultural production. His Three Studies is no different in this respect; and it finds the artist at his most rigorously pessimistic. Emerging from the rubble of lockdown, expunged of civility and absent any semblances of propriety or decency, the work is nonetheless possessed of an insouciant beauty.

Three Studies is drawn from the dry well of Outer Limits, a database containing hundreds of digital images of moulds the artist took of his penis, using tissue paper, after he had masturbated, something Ó Raghallaigh says he indulged in compulsively for the duration of the lockdowns.

The work channels the cultural vacuity into which Ó Raghallaigh says we are being sucked, a death spiral intertwined, intimately and inexorably, with societal breakdown, environmental degradation, and the planet’s sixth mass extinction event.

The professional cultural managers—Ó Raghallaigh’s nemesis—are, although they do not know it, steeped in what Ó Raghallaigh terms ‘the masturbatory imagination’, where auto-erotic vectors of personal advancement are discharged into the fabric of the collective imagination, as projections of socially engaged and environmentally friendly identities. Aligned with dominant economic and political forces, they sift the coarse-grained rubble of a despairing world for assets into which to sink their index-linked, statue-driven teeth.

“The degradation I experienced during the lockdowns,” said Ó Raghallaigh, in a recent interview, “through compulsive and habitual masturbation, showed me that when push comes to shove the nobility of the human spirit can begin to look a little off colour. My artistic practice, for what it was worth, was reduced to servicing sexual urges that provided but passing relief.”

Stripped of ameliorating colour, Bacon’s studies have been reduced to the bare essentials. Resembling husks or shells, they are all that remain of Ó Raghallaigh’s pandemic desire for the intimacy of physical connection, a desire that was unable to connect or interact, except with and through the artist’s curdled imagination.

With a return to flaccidity the tissue paper in which Ó Raghallaigh’s sexual organ was bound descends into photographic representation and the deadening axioms of artistic accomplishment. Its spent payload of generational reproduction and species survival resurfaces as an image for our visual consumption.

A hood. A balaclava. A hollow testicle.

The first study resembles a hood, a balaclava, a hollow testicle. It is not so much a study for a figure as a covering for a figure or part of a figure that isn’t there, an empty shell from which a figure might or might not emerge.

Instead of a figure we get a hollowed out study, a study that is studying the figure’s absence, and its own emptiness, as a form of extinction, one of three locked-down figures that have emptied themselves of their desires to be figures. They are stained with the grief-stricken seed of material manifestation, a seed that mourns and laments its own presence, and the artist’s inability to connect and interact.

Such a seed scuppers the imagination and makes it go flaccid, when what is required is a return to the cold hard cash of arousal that can compel us to dream and consume. But arousal stimulates and reinforces production, which further hastens and enhances a culture of consumption and over-production that leads to increased biodiversity loss and environmental degradation.

So this first study is ostensibly a study for a figure that does not or will not exist in the future, and yet we imagine there is a head inside the hood. So we think that must be the figure being studied, a figure resting on its side, a ghost figure, a figure dead or sleeping. The absence of this figure makes its presence all the more palpable. Its photographic incarnation is a mortal wound that renders it both potentially and already extinct. The artist has let it be known that after he photographed the moulds he destroyed them.

That the contours of this head are connected, intimately, to Ó Raghallaigh’s genitalia is both material and immaterial to our aesthetic evaluation of the work, something not lost on the artist. The die has been cast within an imagination caught between the commercial hysteria of the market and the incendiary violence of a fast approaching future.

The tissue’s fragility, where its form and structure derives from, conjures a sleeping beauty that functions as a Trojan horse. Ó Raghallaigh has laced and undercut his aesthetic accomplishment with a rude awakening.

Faced with such a dilemma, the imagination reacts by filling in the gaps in perception, to move the narrative away from its origin story and replace it with something more edifying. A covering for a head contains an invisible head, and with it an invisible body. We feel the head tilted downwards. We sense the eyes downcast. We imagine a body lying on its side, fatally wounded, contemplating its potential non-existence, the portent of an emergent species extinction.

This sense of injured or offended reflection calls to mind the Roman sculpture of The Dying Gaul, also known as The Dying Galatian and The Dying Gladiator (1st Century BC, Capitoline Museums, Rome). This tenuous association is fleshed out in the second study, where pacified desire segues into anguished frailty.

In contrast, the first study is reminiscent of a bleached, hollowed-out Guylian chocolate seashell and an ashen hijab, associations that contain an array of allusions and insinuations.

The mould’s scrotal contours and furrowed marbling migrate within the imagination from its physical origins to myriad resonances and resemblances, all of which are out of the artist’s, and the viewer’s, control.

But as the narrative progresses, we are drawn back into the quagmire of the work’s inception. Imagination on the rampage, sowing its wild oats, mirrors mass extinction, as allusion after allusion, insinuation after insinuation, is devoured in an orgasmic frenzy of consumption.

As studies for endangered figures, the work breaks free from these allusions and insinuations, slipping between the portals of the imagination, stealing through the ornate apertures and decorative crevices of aesthetic refinement, as something whispered under the breath, between clenched teeth, behind pursed lips, a candid, unguarded murmur of prostrated affirmation.

A cavity. An orifice. An empty socket.

In contrast to its predecessor the figure in the second study resembles a headless body, a torso caught in a spasm of some sort, most likely sexual—as much dying gall as Dying Gaul. The study is a view of the figure as cavity, as orifice, a socket empty of the thing it is designed to contain, which once again draws the willing eye back to the flawed pedigree of its means of production.

The extinction event for which the figures being studied are intended has seeped into and embedded itself within the forms, as sites of infestation, violation and defilement, but also as objects of confinement and containment: wounds, cavities, orifices, caves, dungeons, craters, crevices, purses, pouches, wallets, pockets and sacks.

The circumstances in which the moulds were created, the pandemic lockdowns where the artist experienced a protracted dark night of the tissue, is revealed to be integral to the structures of the studied figures, within the logic of their fidelity as moulds to the thing around which they were formed.

The oppressive nature of unfulfilled desire reproduces itself and is reified in the diversified emptiness of the moulds and the visual associations the wound of their photographic incarnation engenders.

Frozen in a spasm of agony or ecstasy, the central study balks at its own gaunt, disjointed rigidity. Its legs are fused into a tale or flattened fin. Its shoulders open as a gaping vaginal mouth, the oval aperture birthing an ‘Ooh!’ or ‘Ah!’ of disintegrating selfhood.

The second study is a fish out of water, a carcass pulled from the depths of lockdown, leading us into a subterranean realm of the tersely heterogeneous.

Imagination sets to work, stitching, patching, mending, and manufacturing. Putting things right. Making things up. Setting things straight.

We imagine the figure under scrutiny as a composite: part cuttlefish bone, part toothless jaw, part severed hollow tongue, part pelvic socket, part sex toy or therapeutic sex aid, part bio-prosthesis.

We tell ourselves it is an image of a work of art, a version of the Dying Gaul, dragged through a hedge backwards by Pablo Picasso, Alberto Giacometti, Marcel Duchamp, Georgia O’Keeffe, Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth, and Louise Bourgeois.

The artist has supplemented the first study’s hollow testicular head with a study of a vaginal body. The correlations with masturbation are unavoidable: subjective desire and depersonalised object, the hollowing out of artistic autonomy, an ejaculatory death of the self, an intensely pleasurable, as-nature-intended, temporary or maybe not so temporary, extinction.

A yelp. A yawp. The Dying Gaul perks up.

The third study is a riposte to the previous two. The figures under scrutiny have been reduced or condensed to a naked yelp, a licentious yawp, the moulded tissue paper wracked by an amalgamation of sexual longing, sexual frustration and sexual release, undercut by grief and melancholy sadness.

Upon closer inspection we see that the third study is the first study spun around and flipped over, so that the hole in the balaclava is now facing upwards. The testicular head that was tilted downwards has become detached from its imaginary body and appears more like a disembodied mouth, not singing for its aesthetic supper like the second study, but piercing the air with a silent shriek or scream, similar to the one emitted by the figure on the right in Bacon’s original.

Mouth on mouth. Silence on silence. Silence overlaid with silence. Silence buried under silence.

From figure to figures. From figure to figures to species of figure.

From creation to domination. From domination to extinction.

On. On. Overlaid with. Buried under.

From to. From to to of.

From to. From to.

The Dying Gaul has perked up and is repurposing his demise. He’s girded his semen-stained loins and is preparing to bear witness to his own aesthetic immortalisation.

This third study contains elements of the other two studies. As such it prepares the way for an understanding of each of the three studies in terms of a study for an extinct figure, which taken together represents a species of figure.

Hard graft. Lingering gaiety. Bankrupt assumptions.

Echoing Bacon’s three studies, which were ‘for figures at the base of a crucifixion’, the work hangs like an impenitent thief between the need for physical connection and interaction the lockdowns created, and the wounds inflicted upon the artist by his imagination for his failure to satisfy such needs.

This returns us to the cycle of inconsolable longing and unsated arousal that leads to renewed material production and consumption, which in turn stimulates and reinforces the deliriums of mass-production and intoxications of mass-consumption.

Taken together the three studies are sweet wrappers for sweets that are more bitter than sweet, more hard graft and grindstone than the unmitigated bliss of beating one’s meat.

Expunged of their figurative payload, an expectant festivity and gaiety linger on, in doomed and dishevelled shrouds for figures that we suspect have already made their exits.

These are figures for whom being studied is something terminal, a death sentence to usher and ease us into thoughts of our own extinction.

Ó Raghallaigh’s photographic vignettes are whited sepulchres for bankrupt assumptions: the assumption that humanity will always be here, the assumption that nature will always provide, the assumption that the dilated aperture of the earth’s cornucopia will never diminish, that the earth will never cross its legs and say not tonight honey, even though we continue to plunder and exploit it and each other, as mournful and repentant ghosts, already and forever absent, lost to ourselves and a world that’s already dreaming of a life without us.

_________________________________