In Staro Selo, a deprived neighbourhood in Bulgaria, everyday lives are dominated by crime, fear, and violence.

It is a dark place, cold and bleak, where the snow blankets the blood on the streets and the wind silences secrets. The neighbourhood is ruled over by Ginger Dimitar, the tyrannical owner of half the town. The residents live in constant fear of his control, and go silent when faced with his tyranny.

The novel is infused with a feeling of claustrophobia. The residents are trapped, and whoever leaves is referred to as a coward or aloof. In Staro Selo, life repeats the same old cycles. Time is a powerful theme in the story. Time, in the sense that fates can change in a heartbeat – attitudes can turn, anger can rise, illness can fall as quickly as hailstones – but also in that things never really seem to change.

“It kept raining; the weatherman said that a cyclone or maybe an anti-cyclone could roll around these parts for a whole week; it would cause rivers to overflow. Climate change, damn it; we were walking around in T-shirts in January! Then in March, the polar bears turned up to break our necks. The wind whipped and whistled. At one point, it started howling so strongly that the rain hid in the sky, and you couldn’t work out if it was raindrops or sky falling before your eyes. A camel coat came out of the house. The horoscopes said this was colour was favourable in all aspects of life this week.”

The community can predict the actions of the town’s tyrannical resident – Ginger – when Elena, Staro Selo’s local healer, steps out of line. Warnings come unfiltered. Neighbours hide indoors when they smell trouble on the air.

But then we are struck dumb by moments like this one:

“Two kids strolled along the street, bathed in sunlight – not a street, but a treasure trove, all the house windows were diamonds.”

Moments of beauty. Of clarity. Of seeing through the grime and poverty to a moment of light. Evtimova balances this light and dark throughout, painting community that survives by the skin of its teeth, but that also sees joy and wonder in the faces of friends, in healing abilities, and in friendship. Here, it’s worth noting Yana Ellis’s work to translate Evtimova’s lyrical, dream-like prose. The language throughout the novel is exquisite, bursting with juxtaposing portraits of poverty and spectacle.

“The kids didn’t know God often stops by in Staro Selo and even more often transforms into a tiara and shines in a girl’s beautiful hair. Like this, her face is clearly visible even after dusk.”

But with awe comes fear, and segregation. Evtimova sketches out life in Staro Selo through a range of narrators and viewpoints. We see action unfold through the eyes of both elders and children, hear their stories through spoken word and letters. And while each voice is distinct, when read together we begin to learn how each individual is simply trying to survive with whatever skills or assets they have been born with. Like old Damyan and his beauty, remarked upon by all who see him, or Siyana and her keenness for mathematics.

But it is Elena who carries us through the novel. She is the nucleus of both the story and Staro Selo. Around her, her family tries to cope in their own way with love, loss, and poverty. She is both witch and doctor, quiet yet powerful. She alone stands up for the injustices that she and her neighbours endure, from violent attacks to vandalism. She is the strength, the backbone, to which we readers cling, hoping that good with triumph over evil.

Light and dark, good and evil. Themes associated with fantasy, yet here entwined with realism. Evtimova evokes the Eastern European tradition of using fairytale-like structures, ambiguous magical elements, and dreamlike language to discuss hard, often brutal real-world issues. This technique – while harking back to old traditions of oral tale-telling around the hearth and heart of the home – offers a veil for both author and reader. For Evtimova, the veil allows her to depict situations where the reader must pull back the veil to the truth themselves, thus inviting the reader in closer to the domestic settings within Staro Selo. For the reader, this device offers a sense of control, but also allows for more interpretative reading, with some readers choosing to take the story at face value, and others delving deeper into Elena’s story as allegory and fable.

While Evtimova seamlessly brings together the fantastical and the true, it is never gratuitous. We’re often left with the feeling that imagining a more supernatural way of things is the only way to cope with the entrapment of Staro Selo. Seeing beauty and wonder where they can provides an escape, and enacting small moments of what feels like witchcraft is a way of creating a moment of purity in the grime of the neighbourhood.

The author, Zdravka Evtimova, born in Pernik, Bulgaria, was raised in a community not entirely dissimilar to Staro Selo. She speaks of running wild with local children, and her strong-willed mother driving a pin through her tongue as a punishment for uttering a swear word.

Evtimova’s work interprets her beginnings through fictional landscapes that not only reflect the brutality of poverty, corruption, and marginalisation in a close-knit setting, but also the fierce, unquenchable strength that exists in community.

Evtimova is a prolific writer, whose literary contributions include seven novels and eight short story collections. Her stories have been published in over 30 countries, and translated into multiple languages. She is also a translator in her own right, and her work has been instrumental in bridging cultural and linguistic divides, enriching both Bulgarian and global literature. But when it came to translating The Wolves of Staro Selo, Yana Ellis was able to bring her own interpretation to the text. Drawn to narratives that explore issues of identity, immigration, and the ‘other’, Ellis’s fascination with local history, coupled with her skills in rhythm and lyricism meant that Evtimova’s poetry wasn’t lost, and neither were the meanings behind referenced community folk tales.

“Then I drank your tears, one by one; they were salty and light like nimble fingers that cure the most terrible of illnesses – loneliness. I told you the old Radomir story, about the tears and the special friend.

“You said, ‘I have no tears in my thoughts, Christo. I have eyes in my fingers. They see that I’ll never meet a better man than you.’

“What a stupid thing you said.”

Here, Christo, the handsome yet naïve son of Elena, performs part of an old local tale to demonstrate to Siyana the force of his love for her. In return, Siyana – clinging to her childhood passion and skills for mathematics – repeatedly reminds Christo of an equation which – when solved – gives the answer of love.

The interactions between Christo and Siyana are mostly remembered from before their relationship went sour, but even here, we see the classic abrasive communications which are typical of Staro Selo. Siyana cannot truly play along with Christo’s story, and neither can Christo ever solve Siyana’s algebraic problem. In this town, voices and characters are strangled by those with power, and so turn inward to preserve themselves, whether this is joining with those at the top of the power-tree, or by abandoning their own family to work in a different country.

Perhaps then, the reminder that Staro Selo’s ‘most generous place’ is Second Chance, the second-hand thrift-style shop, is the true hero of the tale. Though the shop be ‘dark as stout inside’, it offers the local people a steady stream of ‘sweetest happiness.’ Here, you can walk in as one person and leave as another, wearing a new skin, ‘nearly new’ and ‘feeling gorgeous’.

Simply another kind of escape.

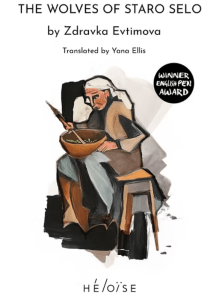

Zdravka Evtimova (Radomir, 1959) is a Bulgarian author and translator, winner of numerous literary accolades. Her novels and short story collections have been published in more than ten countries. Her short story “Vassil” was one of the award winners in the BBC international short story competition. The short story collection Pernik Stories won the Balkanika award for Best Book of the Year. The Wolves of Staro Selo has been published by Héloïse Press.

Yana Ellis found her ideal career in her middle years and graduated in 2021with a merit in her MA in Translation from the University of Bristol. She was shortlisted for the 2022 John Dryden Translation Competition and in the same year was awarded an ALTA Travel Fellowship. She translates fiction and creative non-fiction from Bulgarian and German. The Wolves of Staro Selo is her first full-length literary translation.

Caroline Hardaker lives in the north-east of England and writes quite a lot of things, mainly dark and brooding tales exploring everything speculative, from folklore to future worlds. Author, poet, novelist, librettist, and sporadic puppeteer, her work has been featured in The Washington Post, The Guardian, and New Scientist, and was shortlisted for a Golden Tentacle Award (The Kitschies). Caroline’s debut novel, Composite Creatures, was published by Angry Robot in April 2021. Her most recent novel – Mothtown – was published by Angry Robot in November 2023. Caroline’s debut poetry collections, Bone Ovation and Little Quakes Every Day, are published by Valley Press. Find out more on her website: https://carolinehardakerwrites.com/