The New York Review of Books began publishing books in 1999 and has several imprints. It provides a nourishing variety of books for the serious reader: offering books in translation, republications of neglected classics, children’s books, poetry, criticism and essays. The editorial staff of the book publishing arm of the New York Review seems to possess the necessary fervor and devotion so committed do they appear to the idea that good literature can bring about a better world. I commend them for their efforts and, I should add, I too believe in their cause. The world is not a spiritual place in most of its corners these days, but there are still good books to be found if one is willing to look and it is by those means one is able to find one’s self in another world and see through another’s eyes. Perhaps I exaggerate in order to make more emphatically my point which is this: the New York Review of Books has published great books for a number of years now and continues to do so in spite of the current unfavorable climate for publishing and a population increasingly distracted from reading actual books. Granted, the future might be bleak, yet it is organizations such as the New York Review of Books that give us hope.

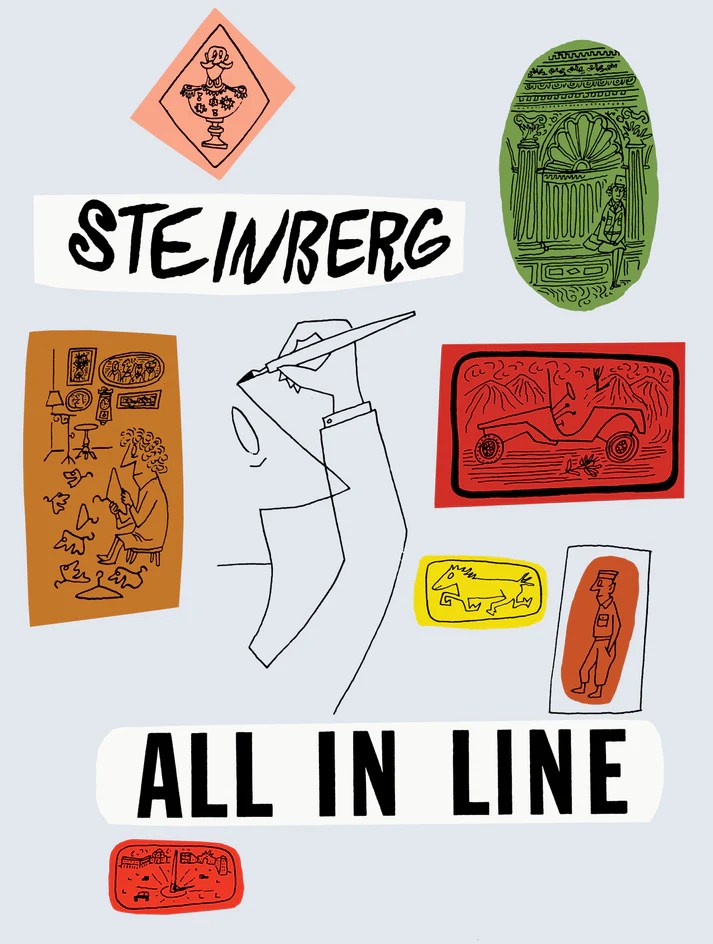

Thus was my frame of mind when I recently received with the greatest pleasure Saul Steinberg’s ALL IN LINE, published by New York Review Books (NYRB), in 2024. Originally published in 1945, All in Line is Steinberg’s first full-length cartoon collection. As Ian Topliss writes in his afterword, Steinberg’s book “was a triumph when it was first published”. Sales were good and by 1947 a paperback reissue would be prepared for the American mass market. Though Steinberg wasn’t particularly pleased with this reissue, he was at that point well on his way to establishing himself as a recognized artist in the world of top-tier print publications.

Steinberg’s book gathers from his earliest work as a creator of gag cartoons to drawings he made while under the superintendence of the Office of Strategic Services during World War II. Not surprisingly, there’s a noticeable shift in the book’s tone as it moves from those earlier creations to those found in the following sections titled ‘War’, ‘China’, ‘India’, ‘North Africa’ and ‘Italy.’[1] The surreal whimsy of the opening section, delightful and charming, often richly child-like and silly-seeming, is soon replaced with a different kind of seeing, a precise observing and taking note. Those drawings Steinberg made while serving abroad are unmistakably in his style but there is something of the correspondent in his purpose, an element clearly sensed: he wants his audience to see what he sees and feel what he feels in this distant world strained by the horrors of war.

At the start Steinberg has his interests. He is wonderful at depicting simple activities by means of simple uncluttered lines. A woman folds coat hangers into smiling faces and one dog. Four men on a street corner tilt heads in perfect alignment to read from newspaper piles. A sleeping mother dreams of counting sheep with baby sheep while her baby sleeps beside her. Steinberg was good drawing drunks. A man lies on the floor passed out, drink at his side, a concerned looking dog keeping watch on his chest. In a saloon a drunk takes up three bar stools, horizontally unconscious, like a stiff plank. Steinberg’s interest for the down and out, it should be stressed, is never condescending. His drawings are acts of delicate empathy. They might make us laugh but he insists we do so without cruelty. It is Steinberg’s strength, his great humanity. He also loved to draw mothers and children, large mothers in great warm coats and hats, small children in great warm coats and hats. Two mothers meet and smile at each other, while below them their children exchange glares. One drawing has a mother proudly marching her family, as she looks over her shoulder at a dog, who is similarly marching her adorable puppies. Their shared look suggests an emotional bond that transcends species. The pride of motherhood, Steinberg says in his cartoon, can be seen in all created beings. One cartoon has a large mother decked out holding the hand of her tiny charge. They are in an art gallery. The mother wears a hat with veil. They stand before a painting. If you look closely, you see the woman is ever so subtly looking not at the painting before her but down at the girl whose hand she holds. The woman knows clearly where the true work of art is. Both woman and little girl share the same tiny familial feet.

Few of Steinberg’s cartoons use language. He was Romanian by birth, English was his second language though he could speak and write proficiently enough. In many respects, his model is Chaplin. The visual is silent and doesn’t require language. Though there are moments when his cartoons, especially the early ones, make use of brief captions. Two medics carry a man on a stretcher. The man on the stretcher is standing upright, hands in pockets. The medics are approaching a doctor. The lead medic says to the doctor, “He feels better.” Another: two men standing at the end of a dock looking out at a man in the water. The man in the water is crying out, “au secours! au secours!” One man says to the other: “If’s he’s not a Frenchman he’s certainly an awful snob.” Good gag lines, but it is in his silence that Steinberg maintains his purest moments, the full measure of his humanity expressed by subtle means. In one cartoon a woman sits behind a young girl who is practicing the violin. The woman weeps, dabbing a handkerchief to her eyes. Is she crying because the child’s playing is beautiful or horrendous? As any parent or music lover can attest, it isn’t always easy to tell. An optometrist is looking at a patient in an examination room. Before the patient is a gigantic letter A. The optometrist has a look of sheer exasperation on his face – the look is rendered by wide eyes and a simple straight line to indicate the mouth. His face seems to be saying, ‘you’re kidding me?” Yet it is Steinberg’s sympathy that comes through. We’ve all been the optometrist in certain situations and we have all been that patient looking at a gigantic letter A unable to see it. One other cartoon deserves mention, since it indicates his European sophistication lurking behind an art form not usually associated with that trait: a boy is drawing with chalk on a sidewalk. Three men in business suits look down at the boy’s handiwork. It is the outline of a woman. The boy has given her naked breasts. The men haven’t noticed that luscious detail. And the boy wears a mischievous grin.

Leafing through the pages of All in Line, one must work hard to avoid the impression Steinberg took real delight in drawing mothers and children, artists, musicians, drunks, dogs, large rooms, crowds, sidewalks, animals, curtains, framed paintings, flowers, facades. His artist’s eye was charmed by the ordinary gesture, the outlined figure. If shapes are filled in, such shapes tend to be placed far in the background.

The section entitled ‘War’ is the least appealing in the book. Here Steinberg seems constrained both by the horrors of the subject matter and the obligations of his office. This is Steinberg employing his skills in the service of propaganda, a necessary task but one that seldom results in the creation of great art. A variation of the mother and her children motif is presented: a mother in full-Nazi regalia pushes a stroller decked out in Nazi insignia. The stroller has attached to the front a portrait of Hitler. She salutes Hitler. Her children in the stroller, similarly bedecked, salute Hitler. It is a sickening little cartoon that conveys the sense that Hitler’s hateful cult had infiltrated all aspects of German life, even the most domestic of activities is corrupted. This section contains the longest instance of Steinberg using text. Hitler and Mussolini write a letter to Santa:

Dear Herr Santa

Since 1939 we have asked you

please to bring us der Viktory

We have been waiting for one

so long you know how

good we are

Adolf

Benito

P.S. Our patience is at an end

We suspect you are not

aryan

[page 51]

The drawing depicts Hitler as a dandified father and Mussolini as a child in a dress with a bow on his head. Angels wearing German helmets play musical instruments and float in the air. In the far corner is a noose. Hitler leans on some ghastly tripod for holding a garden vase. This drawing has an ugly splotchiness unlike Steinberg’s usual lightness and balance. It befits the subject matter and meets an obligation. One last cartoon, a silent ancient tragedy, has death dressed as a German military commander, striding forward, arms raised, in the background, the ruins of a devastated Europe.

The final four sections headed ‘China’, ‘India’, ‘North Africa’, and ‘Italy’ show Steinberg’s eye and hand still in the service of the military but he is embedded now and so he is travelling. His role is less ideological and more reportorial. The result is work that has an immediacy to it, the senses fully engaged. Perhaps these cartoons exhibit the mature Steinberg style, or perhaps it is a matter of his art finding itself once given greater freedom from the burden of an overt political obligation. Most definitely Steinberg’s art gains in authenticity in these sections. As the American troops move into foreign lands, Steinberg works to record both their circumstances, the landscape and towns they enter, and the gaze of the people whose lives their intrusive presence disrupts, disturbs and amazes. Steinberg pays great attention to people looking at these strange American servicemen: in one drawing the tiny heads of children can be seen peeking into a window of a room where soldiers are temporarily housed. In perhaps the most chilling realistic cartoon, a soldier stands in a rice field and shoots a snake with his pistol, while behind him a field worker struggles under a shoulder yoke balancing two buckets. In the distance a woman has a baby on her back. Why did the soldier just shoot the snake? No answer is given. One field worker has raised his head to look at what has transpired. His expression must be examined closely: it is a look of bewilderment and concern. Of course, as the military traveled in these countries many activities were mundane. Steinberg records these with precision and without glorifying them: soldiers eat in restaurants; soldiers buy items in shops; soldiers work on vehicles; soldiers read letters from home; soldiers sleep and dream of naked women. Often the poverty of the country that Steinberg finds himself in is suggested though never dwelled on. His is a subtle art, leaving much for the attentive viewer to ponder. One can imagine Steinberg working quickly, even in public where an audience might soon gather about him as he drew. At times Steinberg’s art assumes the status of testimony. He is a brilliant cartoonist. One believes he is an honest witness too.

The section on ‘Italy’ might contain the book’s finest work, most of it dated from the year 1944. A solitary jeep drives down a city street, the city on either side reduced to rubble. Servicemen pause to eat K rations. They look ordinary. They do not look like conquering gods or even heroes. A soldier stands upon a chair and reads beneath a low-hanging light-bulb his letter from home in the form of V-mail. (V-mail was the required format for writing letters to servicemen: letters had to be written on special paper which was read by censors. Once letters passed the censors they were photographed, then transferred to microfiche and sent overseas as a large batch mailing. When the microfiche arrived at its destination the letters were then enlarged to 60% of the original size and delivered to the soldiers. The system freed up an enormous amount of paper for the war effort.) Servicemen walk city streets. They pose with arms around girls. They look at women passing by. A soldier sits on a box in undershirts smoking a cigarette, a gasoline can nearby. Others lounge beneath historical monuments. One has his shoes shined by a small boy. One looks out at sea while another sits alone at a café with his eyes closed. Steinberg is very good with architectural structures, suggesting magnificence, Old World beauty, and he does so often in his Italian section though the military presence is always there. A large piazza with its central monument, a large tower, sits in the background while in the foreground an American tank and various smaller military vehicles rumble across stirring up the ancient dust. Steinberg saw in Italy the eruption of Mount Vesuvius. He draws that eruption too: a soldier holds a camera and takes a picture. Finally, Harold Ross, the legendary editor of the New Yorker, had a favorite of Steinberg’s drawings from this book. A military convoy winds its way through mountains over an ancient bridge. There’s a town nestled high-up, and another in the distance. What is wonderful about the image is not the convoy but what you see if you look closely. You see people and animals, you see humanity going about its daily chores, you see life in the midst of all that moving metal. I truly believe Steinberg in his heart wanted us to attend to those other details of rural life he saw in the Italian mountains.

[1] The NYRB reissue also includes an ‘Introduction’ by Liana Finck; ‘Afterword: the Making of All in a Line’ by Iain Topliss; ‘Notes on ‘All in a Line’ by Sheila Schwartz; and ‘Captions’.

Saul Steinberg was a Romanian-born American artist; his covers and drawings appeared in the New Yorker for nearly six decades, starting in 1941. “All in Line” has been published by New York Review Books.

Jon Cone is a poet, playwright, editor, and writer who lives currently in Iowa. His recent poetry has been published in SCANT (Manchester, UK) and ant5. His reviews have appeared recently in RAIN TAXI (Minneapolis, MN). He still exists at the dumpster fire formerly known as Twitter: @JonCone.