Writing about Osip Mandelstam right now is difficult for two reasons. The first is that poets whose bodies are subject to state control torture are on my social media feed daily now, from Palestine to Ukraine. So, inevitably, is another self-serving editorial in some middlebrow paper or magazine of record toeing the neoliberal line that “literature shouldn’t be political”. Or that “it’s complicated”. Wouldn’t that be convenient for you, if Mandelstam had never been purged the first time around for writing about Stalin’s fat murdering fingers, if Akhmatova hadn’t had to beg to save his life? Wouldn’t it be nice if we were all easy and silent like some Voronezh pine before its sticky sap percolates down a labor camp prisoner’s axe? So forgive me if I don’t want to step over Refaat Alareer’s corpse to lick the flank of an acceptable mainstream writer’s organization right now, forgive me if I don’t race to see the humanity of the IDF’s butchers spurting blood from the bodies they crush under their tanks and coating themselves in it as tell they us about their “trauma”. Maybe you tell yourselves stories in order to live. Fuck Didion, I’m all Mandelstam now; all high cold clear mornings and new pain and cruelties with reprieves that remind us we must fight to retain the human in the face of them. I tell myself stories in order to imagine them strung up in the Hague in a more just world which I simultaneously know is as impossible as one in which Mandelstam was allowed to live. So forgive me if I cannot be anything but difficult in refusing to grant the mantle of complexity to genocide. It’s all I can be, all I can offer, this small bent thing in the face of it, the wind and the Volga, and weight of human guilt. It’s all I can offer, this refusal, the form of the refusal that is our last laurel, woven into an inadequate and mostly posthumous crown.

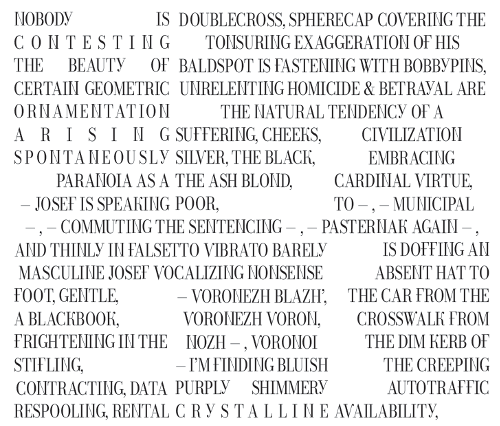

The second difficulty is the silence. I don’t read Russian. My sense of Mandelstam is like walking down a dark hall by feel, by other people’s aggregate translations: Davis, France, Wiman, Brown and Merwin. Then again, a blindfold makes you more sensitive to sound after a while. Then again again, the second order isn’t by nature always inferior. So let’s be difficult together, dearest, my little zvezdochka. This is what Massive is for. When I got it in the mail I thought it was a concrete brick for sculpture. It was actually a galley of a maybe-novel, a book by John Trefry, forthcoming form Inside the Castle press, about among other things, Mandelstam, cruelty, architecture, the etched lines of point, grid, plane, and particular geographies. It is in three fluvial -architectonic columns of sparsely punctuated stream of consciousness solid prose noise, punctured by data. You might hate it, actually, but that’s the point isn’t it, the assumption of risk. The novel, after all, is in some senses a primarily bourgeois form originating in the 19th century, and if the economic era of the bourgeois is exploding into neo-feudal technocratic atrocity, don’t we need a new form? Fat fingers, an axe. Anyway Massive feels like the raw feed of the consequences before the form exists quite yet. Massive isn’t so much an act of reading as of the scream burbling up. This is not a story you tell yourself in order to live, this is not a story, this is a thing that reminds you living is always bound up in the complicities of silence, and that the traditional form of the novel is sometimes one of those complicities. Massive offers something otherwise.

The raw feed of the new form has a caesura or two cut into it precisely where Mandelstam leaves a scar, but also precision measures of raw materials for new and profitable housing developments, Caspian Seas, landlords, displacements, bodies, chickens, onion domes, dermabrasion, and oculi. This is Trefry’s “black algebra”. It’s novel that’s not a novel but a Voronoi diagram, the partition of a plane into regions based on points in a set scattered at random across it. Of course an essay slantwise to such a novel is the higher order example of the thing, partitioning out a plane of novels in which one particular novel exists, or refuses to, and what is entailed by that refusal. RE: Voronoi Diagrams, Georgy Feodosievych Voronoy posited n-dimensional cases in 1908, but basically it arises from the idea of proximity problems, of calculating how close two points can be to one another and gets generalized into tessellated polygons and higher order shapes. I steal here what I think is a most terminologically accessible definition from a computational geometry seminar taught at Brown in 1992-3 by Roberto Tomassia:

In general, the problem we are trying to solve is the following: Given a set S of n points in the plane, we wish to associate with each point s a region consisting of all points in the plane closer to s than any other point s 0 in S. This can be described formally as Vor(s) = {p : distance(s, p) ≤ distance(s 0 , p), ∀s 0 ∈ S} where Vor(S) is the Voronoi region for a point s.

Trefry mentions the “voronoi beyond the tollgates” in the first thirty pages or so of Massive, but the galley doesn’t have page numbers, so you’ll just have to trust me that a basic bitch Voronoi diagram sort of looks like a map. But whatever, the point is or rather points are, that in n-space things start getting more difficult and more interesting even if it’s all still Euclidean. How close is Mandelstam to Alareer? If there is one region Vor(MA) that contains both of them, is there another one close to that that contains the points closest to the problems of modern housing development in Eastern Europe? Another Vor(x) where x is human cruelty but in n-space maybe that can wrap around the whole thing somehow coherently.

Nadezhda Mandelstam, a native of Kyiv, was married to Osip. To save his whole corpus, she memorized it: two points in the same Voronoi region even when one, in his second exile, to which she accompanied him, died of typhoid near Vladivostok. This was interspersed by several other moves relating to exile and arrest; also, Nadezhda only found out he was dead when she had a letter returned to her since the addressee was no longer alive. In the end, the bureaucracy, too, does not bother telling us stories to make living any easier, a theme woven into Massive, whose sinister lurking bureaucratic acronyms sprout up across pages like mushrooms you definitely shouldn’t eat. Mandelstam’s previous period of exile was served in a city named Voronezh, which he supposedly chose for its combined meaning of the words “raven” and “knife”. Corvidae are smart creatures. Ravens can actually use knives as tools. So anyway, I don’t know the Russian, but I do associate these things vaguely with each other, these two points on the same side of a facet of some polygon stretching into goldfinches, Mandelstam’s disobedient goldfinches who curse their prisons in perhaps the most famous poem of the Voronezh Notebooks. Vor (birds). Vor (forced displacements). “When the goldfinch in his airy confection / Suddenly gets angry…” [trans Davis]. The Voronezh Notebooks are full of birds, stubbled, standing against the cold, free, intransigent, relatable, or otherwise so far above the black earth they leave the poet standing there alone.

For me, goldfinches are always Carel Fabritius’ Goldfinch, a 1654 painting in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which is now unfortunately also inseparable in the public consciousness from the Donna Tartt novel of the same name. That novel is not particularly of interest to me now; it does not serve the modes of refusal I am pursuing, the urgency of atrocity closing in. Yet Fabritius does. The goldfinch in the painting is chained to a small metal bar. It is a Wunderkammer creature, kept captive for admiration with other naturalia, except most of the other naturalia are taxidermied and don’t have to live through it. It is a thing with wings that is not free to take flight. It is entirely subject to the power of its owner, whom one can imagine fascinating the small metal cuff to its shaking leg. People often said Mandelstam himself looked like a bird; many of his poems from the prison camps observe them, calling out, voices in the literal wilderness. In the prison camps of Gaza it is now proposed by Israel that Gazans will either have to subject themselves to a biometric regime that tags them or they will continue to withhold food and medicine as they have done for months now. The only thing that flies is quadcopter drones. If Fabritius’ goldfinch tries to flee, it would have to rip off its own leg to sever the metal cuff, and would die immediately. The drones often shoot children.

Vor (sinister enclosures).

A paradox: in theory, literature alone can do nothing. In practice, people get killed for it. Stalin himself took a personal interest in killing Mandelstam. Alareer’s death followed, of all things, a tweet by right wing grifter-pseudo-intellectual Bari Weiss calling him a terrorist to the IDF. The indignity of getting saddled with Bari Weiss instead of Stalin! Massive is full of indignities, but also a continual, almost cosmic interconnection that tessellates sufferings and places next to each other to try to make them mean something. Trefry:

Stalin supposedly asked Pasternak whether Mandelstam was really brilliant, toying with him to test his allegiance to Mandelstam, for whom he had previously intervened. Pasternak supposedly affirmed it. Anyway, one of the manifestations of linear algebra, of tracking the adjacencies of points in n-space, that the Israeli soldiers use to bomb Gaza is named “Lavender”—that purply data. Mandelstam [from ‘What shall I do with this body they gave me,’ trans A.S. Kline]:

I am the flower, and the gardener as well,

and am not solitary, in earth’s cell.

My living warmth, exhaled, you can see,

on the clear glass of eternity.

A pattern set down,

until now, unknown.

Is the novel a point in the same Voronoi region as the poem? Or is it in a separate polyhedron face, faceted out into another dimension? Massive asks this question. Typographically it is formatted like a poem more typically is. In any event the pattern: the region expands along an axis of responding to suffering. And also: to being the subject of political persecution, and the long tail of those persecutions for writing both forms. You want something that isn’t political? Don’t pick a poem. Don’t pick a novel. Don’t pick whatever form this is that is somewhere projected out from it. The politics follows, as natural as breathing, as the growth of subdivisions, as the measurements for basement drywall and skylights, as the black cap of the goldfinch. As the goldfinch straining against the pull of the metal bar frantically.

Massive, as much as it is a novel about Mandelstam and the politics of suffering, or vaguely what that feels like if you try to drink from a server like a garden hose and write it, is also about architecture. Specifically, dwellings, commercial, ordinary, but also endowed with the ability to evoke moments of exhilarating lyricism and association. I look at the composite floor of my new-build one bedroom apartment as I write this. It is probably supposed to look something like the grain of a Voronezh pine. The specifications of composite flooring, or window glass, or interior walls aren’t things you might think offer a particular insight into the question of the form of the novel in the age of atrocity, but you and I would both be wrong in this assumption. These are the spaces in which it is both written and composed; largely generic, “modern” and aware of their own constructed façade of modernity, their perhaps Arendtian banality inside which evil is worked with the aid of far too much paperwork.

Massive, as much as it is a novel about Mandelstam and the politics of suffering, or vaguely what that feels like if you try to drink from a server like a garden hose and write it, is also about architecture.

The generic building is the locus of the question as much as the pine forest to which one is exiled from Moscow or Rome; or more so, now that Moscow and Rome also consist of partly these kinds of housing around the edges; and indeed, so does modern Voronezh. Incidentally, Mandelstam’s first collection of poems is named Tristia, as Ovid named his volume written after his political exile from Rome under the Augustan regime. Ovid was sent to Tomis, on the Black Sea, now Constanța in Romania. Carduelis carduelis the European Golfinch, extends its territory both to the sites of Mandelstam’s exile and to Ovid’s. The goldfinch also migrates to Palestine, where it is حسون, hassoun. In every locale, it is often held captive because it sings so beautifully.

Drywall, terrain, regional authorities, the dangers of singing or saying too beautifully out loud, scraps of old faiths, power, decapitation—these themes are interlinked in Massive. To the extent that the novel is a novel and not an information torrent (debatable!) the reader will encounter pages thick with a dubious entity called Payrite (itself beholden to a nebulously construed fascist government with Soviet traits called the ADA involved with the construction of housing developments), various discrete mathematics in passing reference, actual cells, Golgi bodies, jail cells, and dead pigs. These “c y t o a r c h i t e c t u r e s” are the Voronoi regions in which the novel’s meaning burbles up. Bodies and cities bespeak human natures. Mandelstam rather famously writes about “Mandelstam Street” himself [trans. Meares]:

What is the name of this street?

Mandelstam Street.

What the hell kind of name is that?

No matter how you turn it round,

It has a crooked sound, it isn’t straight.

There wasn’t much about him straight,

His attitudes weren’t lily-white.

And that is why this street

Or, better still, this hole

Was given its name after him:

This Mandelstam.

Indeed, this hole. The hole where you google Mandelstam Street and get, inexplicably but explicably, Frankston, TX 75763, and a small residential side alley triangulated between Maxwell Pharmacy, Family Dollar, and Krispy Krunchy Chicken. It looks slightly more affluent than I expect. There is a house there on street view with a red pickup truck near a two-door garage in a vaguely ranch-style layout. I don’t know though; parts of the truck are rusting. Various roofs need redoing. If you hired Trefry’s ADA to do this, the results would be a sinister intertwining of bodies and historical branchings. You could send a drone to kill everyone on this Mandelstam Street with merely the information in this image. Mandelstam might have understood that, a world where you don’t even need to be Stalin, where everything is potential shrapnel. It’s all crooked.

Mandelstam’s own relationship to the idea of the avant-garde was complicated. On the one hand: he resisted a lot of the post-Revolutionary Soviet experiments with language and form that comprised it in poetry and architecture and visual art, originating his style in symbolism. On the other: his sui generis relation to the world was fundamentally trying to do something new, and something contemporary—this is what gets him in trouble with the authorities, after all. In writing an epigram critiquing Stalin he knew he would be killed. This was the point; he liked living, but not necessarily living with the world laid bare as it was, its cruelty, and with the implicit requirement that he stay silent about it. The refusal to silence ensnares both the poet and the goldfinch.

The ease with which so many choose silence now—even when most of our lives are very far from the risk of an autocratic regime—unnerves me. Is this a world in which our adorable social realist novels about the disintegration of marriages or the problems of attractive young millennials in New York and Paris, about the tyranny of motherhood or singledom, about real estate in desirable and undesirable locations, about ourselves at elaborate autofictional distance, will continue to feel sufficient? To me it feels like something formally has to happen here; either we change the form of the novel to speak to the atrocity of the world at its core rising to prominence, to refuse that atrocity implicitly in its being, or we are effectively silencing ourselves into irrelevance. Mandelstam’s corpse was buried in a mass grave with all the other deaths at the Vladivostok labor camp that winter. I don’t even know if they found all the pieces of Refaat Alareer. What do we ask of the novel in the face of this? The author himself describes Massive as “brown noise”. Some will find it entirely unreadable. When I read Massive reading Mandelstam in the age of a new atrocity, I don’t mind this onslaught, because it’s trying to do something to speak to it, vectoring out into whatever strange dimensions it does. It’s all unstraightened now, non-linear adjacencies.

What do we ask of the novel from the pothole in the wavering street made with municipally dictated asphalt in the streetcam view in the fifth open browser tab of the evening? From the felled pine in Voronezh that now via supply-chain efficiencies, becomes IKEA chairposts, indifferently pegged together? From the impact crater of the next inevitable bomb dropped on the hospital, that doesn’t even make the American news? I have no answer but I like seeing you try, that dark ice forming on the river in pieces, each a subset linked into a polygon. I am begging you: give me a novel that is in itself a refusal of this. Don’t tell me another conciliatory story in order to live. Tell me something worth dying for, worth ripping your leg off the metal chain; give me a form of the novel that is algebraic in its ability to refuse but also to address, speak about, scream. Surprise me with this new novel that could be, just as you surprise the untilled black earth with your plow.

A.V. Marraccini is an essayist, art historian, and critic. Her first book, We The Parasites, was published by Sublunary Editions in 2023. Her second book, These New Fragilities, is forthcoming from Seven Stories Press in 2028.

Massive is the 4th book by John Trefry, concerning the life of Osip Mandelstam between his first arrest in 1933 and his death in 1938 transposed into the eternalist block time of a vast nationstate called the ADA and composed in such a way that the text can be read an infinite number of ways and is only actualized by reading, it does not sit inertly as a complete work within its closed covers. Marraccini’s essay will be included in a forthcoming critical volume from Inside the Castle called Decapitating Massive.