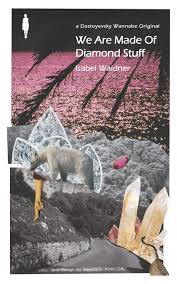

Set on a crumbling tourist resort on the Isle of Wight, Isabel Waidner’s novel We Are Made of Diamond Stuff interrogates the intersections of class, gender and nationality, and the lingering impact of empire on modern British society. Bringing in elements from science fiction, experimental novels and working class culture, Waidner is reclaiming avant-garde writing from the elite, whilst distorting and laying bare the form of the state of the nation novel. Their previous work includes Liberating the Canon and Gaudy Bauble, both published by Dostoyevsky Wannabe.

Last year, you edited the anthology Liberating the Canon, a manifesto for an intersectional and experimental literary avant-garde. How has working on that book influenced your work on We Are Made of Diamond Stuff?

It’s more accurate to say that Diamond Stuff influenced Liberating the Canon, rather than the other way round. I started writing the former in December ’16, and work on the latter not until September ’17 (towards publication in January ’18, a quick turnaround). My objective for Diamond Stuff was to write a highly contemporary novel that performs a queer working class culture and subjectivity in both, form and content. In order to achieve this, I made the strategic decision to work across formal distinctions that in my view have contributed to the normativity of the historical avant-garde canon, including disciplinary limitations, formal distinctions between prose and poetry, and traditional high and low culture distinctions. Re the latter, I’ve introduced a narrative strand based on the character of Eleven from the Netflix series Stranger Things, a deliberately mainstream reference, as well as borrowing one of my villains, House Mother Normal, from B. S. Johnson’s British avant-garde novel from 1971. I’m 100% working against the idea that formally innovative literature now should be this rarefied thing, of interest to an elite readership with a very particular educational capital only. One of my main ambitions for Diamond Stuff was that it should be formally aspirational *and* have the potential to be popular to diverse readerships at the same time. I’ve started to apply the term interdisciplinary writing, as well as formally innovative or avant-garde writing, to describe my work, which I know the writer Maria Fusco has been championing. To get back to your question: I’ve developed my understanding of what a more popular, inclusive, politically relevant, queer and working class form of literature might look like in the process of writing Diamond Stuff, which influenced my editorial policy in Liberating the Canon.

Your novel is set of the Isle of Wight – first of all, what drew you to that location?

The Isle of Wight, and maybe seaside towns more generally, lend themselves as catalysts to explore societal class inequalities in Britain. First of all, they occupy this mythical place in the British psyche. L, my real-life partner, is Portsmouth working class. She regularly spent family holidays on the Isle of Wight in the ‘70s/’80s, and her and I go there on holiday now.

What’s potent perhaps about seaside towns as a literary setting is how English Riviera mythologies clash with the realities of a tourist industry in decline since the ’70s charter flight revolution at least.

Spain is—or was, prior to the referendum-related slump in the GBP—cheaper. Any ongoing decline has been exacerbated by governmental neglect since 2010. Dereliction is real on the Isle of Wight—place is falling to pieces, the shops on the High Street are shut, half the town is on the sick or the dole or has fallen through the crack formerly known as the welfare system. The Georgian villa, though, in that really out of the way posh part of the island is ok. Passed down the family through generations, no one’s in it much anymore. Worth holding onto because sea views.

In Diamond Stuff, the Isle of Wight doesn’t just stand for endemic underfunding, high unemployment rates, former glamour and old Etonian money, but for imperialism per se. One of the thematic strands running through the novel is the embeddedness of empire not just in the British psyche, but in the Isle of Wight’s actual infrastructure and landscape. With countless prehistoric forts in the surrounding sea (against the threat of a French invasion), the island’s proximity to Portsmouth harbour (home of the English navy since the Middle Ages), its role as a key site of defence in the Second World War, and the physical ruins of the historical British Space Rocket Programme left on some cliff, imperial violence is basically one with scenes of natural beauty down there. Imperial violence is literally naturalised, which I know is news to precisely no one, but working through a specific example (the Isle of Wight’s landscape) really brought the truth home.

It’s an important feature of We Are Made of Diamond Stuff that you explicitly acknowledge the structure which surrounds your narrative, and the ideology which shapes the world your characters inhabit, for example colonialism, capitalism and class. It seems to me that the typical ‘state of the nation’ novel alludes to these factors, but rarely acknowledges them so directly. Was this something you wanted to do from the outset?

As a queer working class writer, colonialism, capitalism and class 100% shape my work. Similarly, these realities and systems of oppression are foregrounded in the work of those writers and peers I’m inspired by. But typical state of the nation novels as you call them are also 100% shaped by and within colonialism, capitalism and class – it’s just, their writers tend to occupy positions of privilege within these same systems which is why they (the systems) tend to recede into the background.

Privilege is entirely normalised within literature – its conditions disappear from the text.

This Spring, I was commissioned by Dundee Contemporary Arts to write a text on the occasion of queer artist Patrick Staff’s forthcoming exhibition The Prince of Homburg.[i] I wrote a bizarro play in which I have looked at the normalisation of privilege within canonical literature more closely. Coming in Summer ’19…

Following on from that, what do you think are the risks and benefits of rooting a work so clearly in a defined timespan?

Arguably, the present dates quickly – or does it? Certain historical moments (like now) seem to re-mediate far more longstanding histories (of imperialism, class inequality, and tensions within liberation movements e.g. the LGBTQI+ movement), and this is what Diamond Stuff explores in relation to Brexit. Many of the most exciting writers are writing the present at the moment, I’m thinking of Huw Lemmey’s Red Tory, for example. Most recent queer innovative poetry writes the present, e.g. Callie Gardner’s Naturally It Is Not or Jay Bernard’s Surge, but crucially, in relation to the past.

There’s a sort of anti-realism at work in the novel – as one character remarks, ‘where’s reality? I want to change it’. Is that a reaction to the aesthetic of mainstream literary fiction?

Yes, ok! But it’s also a reaction to the state of actual reality rather than literary realism. Alternate realities and parallel universes are a thing in Diamond Stuff. It might be the proliferation of TV series like Stranger Things and The OA, but it feels like many of us are desperate for alternate realities. I don’t blame us.

Given the state of actual reality, maybe positive prospects and less than depressing futures have to be relegated to parallel universes, or the anti-real realm, literally, in order to be half credible.

In the book, you set out a vision of working class culture defined by the twin pillars of BS Johnson and Reebok Classics. It feels as though the novel is, in part, an attempt to reclaim avant-garde art for the working class, after its appropriation in recent decades by the middle and upper classes. Do you see digital culture opening up opportunities once again for working class people to create and experience experimental art? Or is the establishment art world too deeply entrenched?

Digital culture is definitely opening up opportunities and platforms for working class writers and artists to put out innovative work that reflects their lived experience and cultural context, Minor Literature[s] being a case in point. There’s been a proliferation of queer and interdisciplinary forms of writing in the last few years which is basically unprecedented in Britain, and the digital disruption of the publishing establishment and, for better or worse, social media, are among the factors that have enabled that.

I’m mildly put sceptical as to whether mainstream publishing is actually, structurally transforming – elitism and specifically Oxbridge are deeply entrenched, as you say. The most exciting underground literature (formally innovative writing by writers from marginalised backgrounds) exists very much apart from mainstream publishing and the establishment media, like, in a parallel universe. You’re missing a trick, mainstream publishers 😉

Compared to literature and literary publishing, parts of the art establishment have been extremely supportive of my work. I have already mentioned Dundee Contemporary Arts commissioning my bizarro critical-creative play, and the ICA in London have been supporting and funding the legendary event series I’m co-curating and hosting with artist and publisher Richard Porter, Queers Read This, among other things. There’s a sense of adventure present in our best art institutions, and some individuals with an actual vision…

You’ve built up a relationship with your publisher Dostoyevsky Wannabe, starting with Gaudy Bauble, and moving on to Liberating the Canon and now We Are Made of Diamond Stuff. What impact do you think micro-indies like this have had on the publishing landscape? And how has this style of publishing meshed with your own work?

Dostoyevsky Wannabe are a publisher with huge integrity, generosity and an incredibly diverse set of skills, and yes, we’ve been building a working relationship since my first novel Gaudy Bauble came out in 2017. Our relationship is 100% collaborative and has been from the beginning. We’re in regular dialogue about expectations, ‘strategy’ (?!), and what works and what doesn’t. I’m not buying into the myth peddled by the publishing establishment that it’s exclusively the publisher’s (or publicist’s) job to ‘sell’ or promote a book. I want to understand how selling a book, or reaching diverse readerships, might be achieved differently – ie. *not* via the establishment channels which btw can be quite ineffectual, especially when it comes to selling innovative work. DW and I have none of the typical infrastructures in place (agent, publicist, external typesetters, etc.) nor any mainstream media connections, but we do have a lot of grassroots support within a wide range of fields and my books sell well. In fact, on top of some of the more traditional readerships, we’ve been reaching demographics that do not necessarily engage with more traditional ‘literary fiction’ – for example, readers who are into the arts or a variety of subcultures, and working class readers. Working together, DW and I have acquired an actual competence and understanding of what it means to sell radically innovative books. It involves thinking differently about basically everything and a lot of labour, including on my part.

Amongst all the pop-culture references in We Are Made of Diamond Stuff, the character Eleven from Stranger Things pops up recurrently. What was it about Eleven that especially resonated with you?

One of the main characters in Diamond Stuff is a character who looks like Eleven from Stranger Things but who’s actually 36. One of my colleagues at Roehampton Uni where I work as an academic kept telling me that I reminded her of someone, she couldn’t think who. Eventually it came to her – I reminded her of Eleven, the androgynous child character from Stranger Things! I hadn’t seen the programme then, but started watching it with my partner L shortly after. At first, I didn’t see the resemblance between Eleven and myself. Clear case of misgendering, I thought. It’s not unusual that a straight referential universe should throw up a twelve-year-old with a buzz cut and psychic abilities as the closest possible reference point to a genderqueer in their 40s (me). But the thing is, L saw it too, the resemblance. Maybe I do look a bit like Eleven from Stranger Things!

Fun story, but really, I could have used any figure inspired by popular culture to achieve my project of displacing avant-garde/mainstream and high/low culture distinction in my fiction – see question 1.

Finally, what comes next for you?

I just wrote a commissioned text for the ICA in relation to their I, I, I, I, I, I, I, Kathy Acker exhibition, Class, Queers and the Avant-garde,[ii] which will be published shortly. It’s a weird review of poet Caspar Heinemann’s recent collection Novelty Theory and We Are Made Of Diamond Stuff, making more general points about the need for an expanded review culture in the UK. My main focus for the rest of the year will be to develop some of these ideas into a very unusual book of criticism, redefining the rules of reviewing and profiling some of the queer interdisciplinary writers working right now.

[i] https://www.dca.org.uk/whats-on/event/patrick-staff

[ii] https://www.ica.art/live/class-queers-and-the-avant-garde

Isabel Waidner is a writer and critical theorist. Their books include We Are Made Of Diamond Stuff (2019), Gaudy Bauble(2017) and Liberating the Canon: An Anthology of Innovative Literature (ed., 2018), published by Dostoyevsky Wannabe. Waidner’s articles, essays and short fictions have appeared in journals including 3:AM, Cambridge Literary Review, Configurations, Gorse, The Happy Hypocrite, Tank Magazine and Tripwire. They are the co-curator of the event series Queers Read This at the Institute of Contemporary Art (with Richard Porter), and a lecturer at University of Roehampton, London.